The following is part of our 25-day Holiday Countdown Calendar! Every day from December 1st through the 25th, we’re posting a cool game history treat, daily updates from the VGHF, giveaways, and more! To make sure you don’t miss a day, sign up for our email list:

This is all part of our annual Winter Fundraiser donation drive, where we ask those who are able to generously give what they can so that we can continue thriving. If you’re able to make an additional one-time charitable contribution, this really is the best time to do so, as your donations will be DOUBLED thanks to a generous group of sponsors! Head on over to gamehistory.org/donate to learn more and give today.

Throughout the history of video games, there have been titles that permanently shifted the industry. These games are generally not hard to spot, as their influence quickly earned them a place in our pop culture. Tetris, Super Mario 64, Halo, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, or The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, each of these games caused massive shifts in their respective genres and gaming as a whole. But for each of these, there are also games whose influence, though significant, is largely forgotten. Did you know that almost every 3rd-person cover shooter mechanic originated in the Nintendo 64 game WinBack? How about that one of the first games to feature modern first-person-shooter controls was Alien Resurrection on the original Playstation? Or how about the fact that every 3D game Nintendo has ever made, can trace its roots back to a Game Boy demo developed by a teenager in the UK?

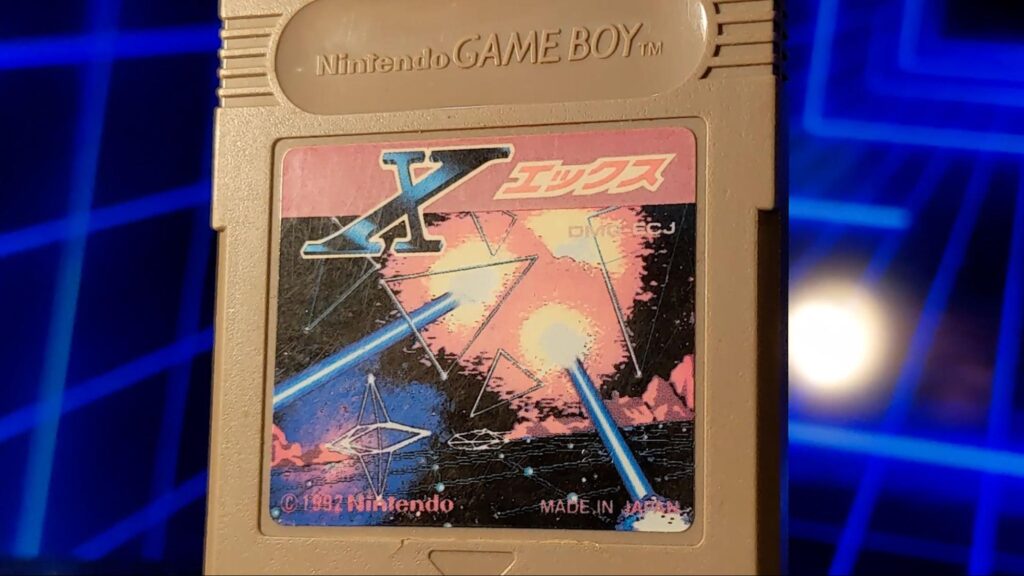

In 1992 Nintendo published a Game Boy game called X. It was based on a demo called Eclipse that was programmed by a young man named Dylan Cuthbert. It would go on to form the basis of the Super Nintendo game, Star Fox. From there Shigeru Miyamoto would begin experimenting with 3D for Mario and Zelda, leading to Super Mario 64 and the Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. Despite its limited, Japan exclusive release, X is generally considered to be one of the most important games ever made. And all of that came from a single, mysterious demo that until now, has remained lost to time.

My name is John Rairdin, I’m the director of NintendoWorldReport.com, and a few months ago I produced a documentary in cooperation with the Video Game History Foundation called A Legacy in 3D: The Story of Star Fox, and had the honor of showing the world Dylan Cuthbert’s Eclipse demo for the first time.

Now I have the pleasure of fully unveiling this demo to you all, telling the story of its development, and how it was found by the team at the Video Game History Foundation.

Today’s Sponsor

Today’s sponsor is StudioMDHR! This indie studio is the brainchild behind Cuphead, a run & gun platformer with a retro animation aesthetic.

…are we really explaining Cuphead? You know what Cuphead is.

They’ve offered to DOUBLE every dollar put toward our goal this year, up to an incredible $10,000! As I write this we’re still pretty far from our goal, so if you’ve been waiting to give this year, this would be a really great time. Producing content like this takes a lot of effort, and if you’re able this year, we could really use your support.

The story of Eclipse begins at Argonaut Software in Edgware, a suburban town in north London. This was a studio run in large part by teenagers and led by a man named Jez San. Argonaut’s specialty was in 3D games for the home computers of the time. Games like Starglider and its sequel wowed players with smooth wireframe, and later fully polygonal, flight combat. Dylan Cuthbert was hired as a programmer at Argonaut at the age of 17.

“It was really just after I started at Argonaut, maybe four months after four or five months after I started at Argonaut… and Jez said, Oh, there’s this thing called Game Boy that’s just been launched in, you know, in the West. And I said, ‘Oh, what’s that?’ And he brought one back.”

One of Cuthbert’s particular talents among the Argonaut team was his experience programming for 8-bit machines.

“I’d learned to program in Z80 on the ZX81 and the Sinclair Spectrum. And of course the Game Boy was a Z80 variant. And he wanted someone who had actually had experience in that CPU.”

This experience made Cuthbert the perfect pick for Jez San’s ambitions for the Game Boy.

“At Argonaut, I think Jez especially kind of prided himself on the fact that he could make 3D run on anything. And when he saw the Game Boy, I think he saw the chance of proving that 3D could run on it. Because obviously it was a 2D machine. No one had even thought of doing 3D on it. But we thought, okay let’s try and do it.”

And so, one of Cuthberts first projects at Argonaut would be the seemingly impossible task of developing a 3D engine for the 8-bit, monochrome Game Boy. A bit of an imposing job on its own, but 3D wasn’t the only hurdle. Argonaut also didn’t have an official Game Boy dev kit. A dev kit is a special variant of a piece of hardware built to allow developers access to programming for a game system that wouldn’t normally be available on a retail model. Instead they’d need to get creative with a Game Boy from straight off the store shelf.

“We didn’t have a Game Boy dev kit and so we were hacking it… I think we took a Tetris or Mario cartridge and we took the top off and then we were wiring the address buses and stuff to go to our Amiga system instead of the actual ROM itself. So then we could just replace the data that was actually in the ROM with our data… We had like a little security camera pointed at the Game Boy screen that was then put on a little TV so we could actually see what we were doing. The screen is pretty small and working on that every day was actually quite tiring on the eyes. So it was a very seat of the pants kind of affair… We started working on it, immediately hacking it and developing a 3D engine for it.”

While Cuthbert was able to leverage the knowledge base of Argonaut to hack the Game Boy and open the doors for their new engine, programming it, and coming up with a game would be entirely up to him alone.

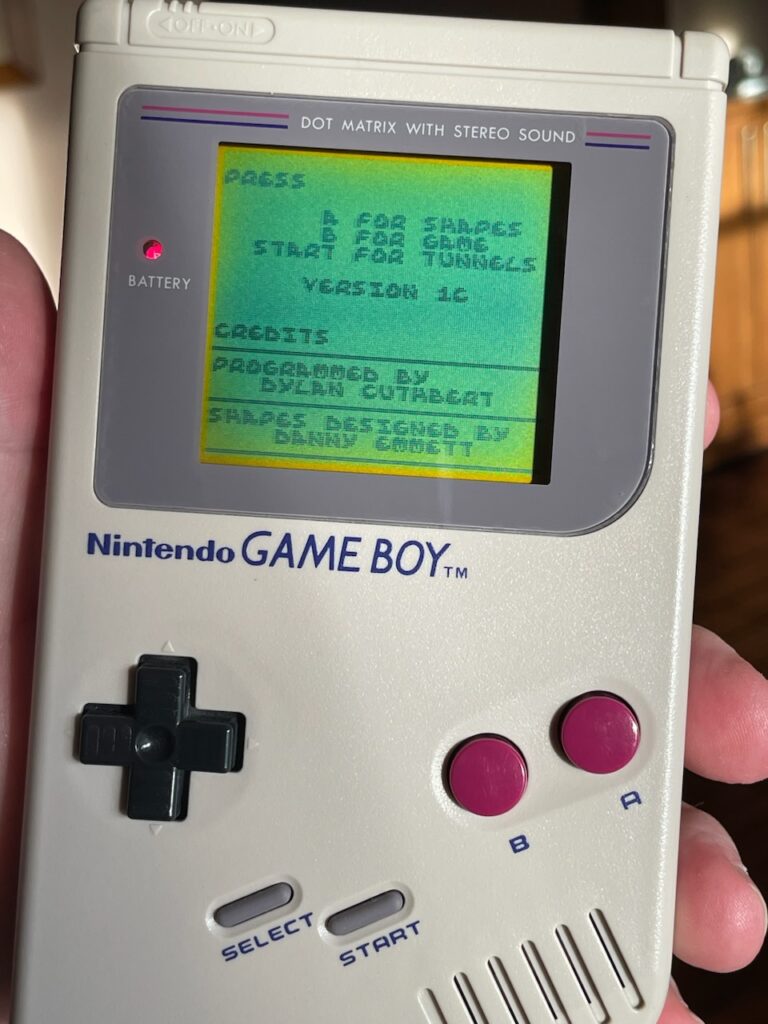

“So it was basically me, that’s it. [laughs] Just me. And then I got a few 3D, we called them shapes back then, to use to test my system with. And then I did all the 2D art and pretty much everything else in the game as well. And some of the 3D stuff was done by me as well. But the cooler shapes are done by a guy called Danny Emmett, who worked at Argonaut at the time.

Initially when I was making the game, I just pulled upon all the games that I liked at the time. And so one of those would have been Ball Blazer. One of them would be Starglider, obviously. And the other one was a bit more of an obscure game for the ZX Spectrum called Micronaut One, which is a game where you fly through tunnels. I’d always been kind of interested in trying to kind of replicate that kind of thing into a game, at least as sort of a sub-part of the game. So I was experimenting with that and trying to get it to work and I got it to work and it was kind of cool. So we included all that into the overall game… The mission structure kind of comes from F18 Interceptor on the Amiga, which is a really cool kind of fighter flight simulator kind of game… it was like the idea of having like this game where you have these very individual missions that are very different to each other, kind of comes from that particular game”

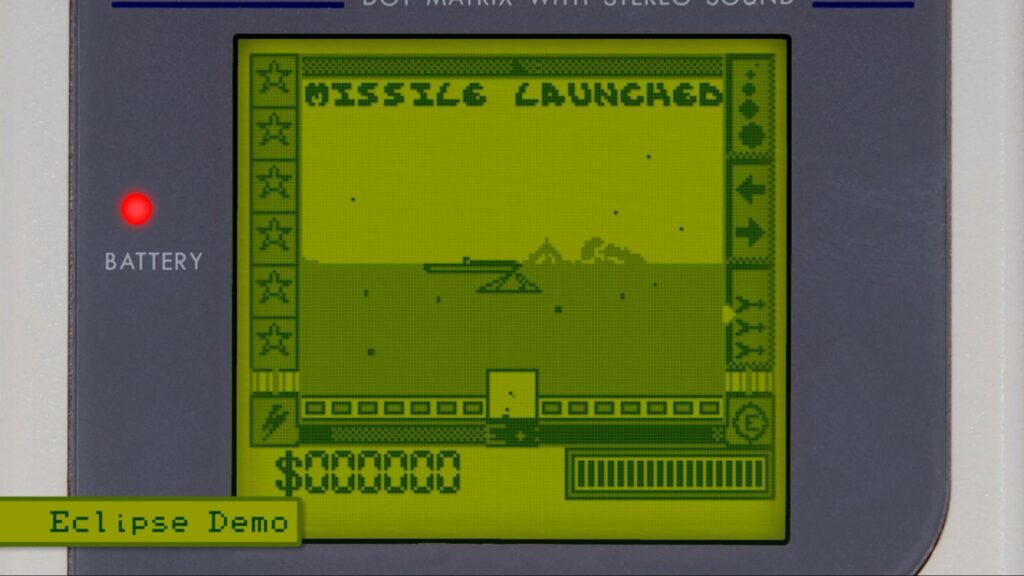

It’s here that I think it’s worth taking a moment to look at what Eclipse actually is in comparison to X, the game it would eventually become. At its core Eclipse is a combo of two different primary gameplay loops. One is a first person tank game. Players are dropped into a three dimensional environment and given an objective to destroy a certain number of enemies while hunting down a certain number of crystals. These crystals would then need to be returned to the base. The entire time players would be burning through precious fuel which, along with missiles and shields, could be replenished by selling off one of those valuable crystals. Once the objectives are completed the player moves on to the next stage, though the state of their tank is carried over.

Between stages the player would fly through a 3D tunnel segment, racing against a time limit. The goal is to move as quickly as possible while dodging obstacles that will stop you dead in your tracks. Make it to the end before the time runs out and you move on to the next combat mission, fail and its game over. These tunnel segments could also be played separately from the demo’s main menu.

The final game maintains this general flow, exploring the surface completing mission objectives, then flying through tunnels on your way to the next level. However, while the final game’s missions are obviously more diverse than those present in this demo, it does somewhat lose the risk reward system of using the very same crystals necessary to complete missions to repair your ship. Rather, in X your objectives and your currency never overlap.

Finally the ROM also contains an object viewer, allowing the player to freely rotate and scale the fully 3D objects used by the game. When played in emulation and blown up on a modern display the objects may look somewhat crude in this low resolution window, but on the Gameboy screen, they were like nothing a Nintendo console, let alone handheld, had ever displayed before.

The demo was then sent out by Argonaut founder Jez San to various publishers to see if they’d be interested in developing the demo into a full game. The demo was initially picked up by Mindscape who already had some experience publishing and developing on the Gameboy with titles like Paperboy, Marble Madness, and Gauntlet II. It is at this point, with Mindscape signing on to produce Eclipse, that our story splits off in two directions. While Nintendo would of course eventually wind up producing Eclipse into a full game. Mindscape’s time with the game would see the demo into the hands of a producer named Mark Flitman. And it would be Mark’s daughter Michelle, who would reach out to the Video Game History Foundation thirty years later.

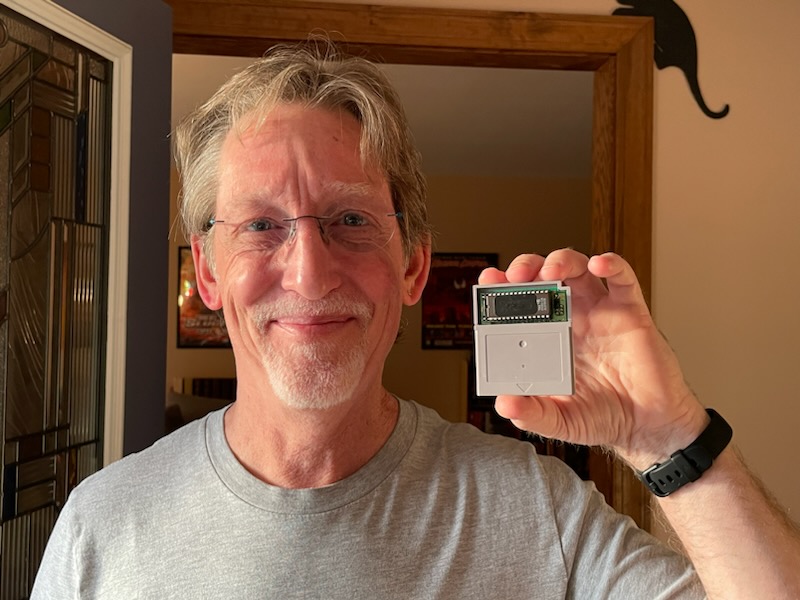

When Michelle emailed the Video Game History Foundation with images of pre-release game cartridges, tapes, and extensive documentation, Frank Cifaldi and Kelsey Lewin wasted no time in getting on a plane. When they arrived at Mark’s home, they found a treasure trove. They set to work scanning physical documents, digitizing tapes, and dumping the contents of the various cartridges. They spent days sorting through the collection, when suddenly a random unmarked Game Boy cartridge caught their attention. It was Kelsey who first checked the mysterious cartridge.

“I plug it in and the first thing I see is the little astronaut and it says ‘by Dylan Cuthbert’ and I’m like, I know who that is!” Kelsey said, “I’m like, Oh my God, this is very similar to X, but also it has all of these other kind of tech demo type things in here. So I immediately knew it was interesting.” Kelsey then showed the demo to frank.

“We’re playing it and we both know enough to go, oh, this is X.” Frank confirmed, “This is like an early version of X. And so, you know, I think it is a pretty easy assumption to go, okay, this was the demo that was maybe shopped around was my guess.”

While Kelsey and Frank may not have known the story of the Eclipse demo at that moment, they knew of Dylan Cuthbert, his Game Boy game X, and the partnership with Nintendo that would eventually lead to the Super Nintendo game, Star Fox. In August of 2021, I produced a documentary on the development of the Nintendo DS game, Star Fox Command.

Shortly after its release Frank invited me to discuss the game’s history with them on their podcast, The Video Game History Hour. During the discussion I casually told the story of the Eclipse demo and its evolution into X. Only to hear Frank wonder aloud if that was in fact the demo they had found. I’d not expected to learn that the demo which served as the genesis for X and eventually the entire Star Fox series, had been discovered while recording that episode. It’s on episode 52 if you’re curious to hear my live reaction.

That is how the Eclipse demo came into the hands of the Video Game History Foundation, but it is by no means the end of the story for Eclipse itself. One of the other companies to receive the Eclipse demo was, of course, Nintendo.

“Nintendo took a bit longer.” Dylan recalled, “Obviously the Japanese HQ had to see it and stuff like that. Then we were flown over to Japan to show it directly and it’s around that time that Nintendo decided to sign it and basically transfer the rights of it from Mindscape. And I still have no idea how or what Nintendo did to transfer the contract that was with Mindscape or how much they paid or anything like that. I’d really like to know actually… And that’s when I started working with Sakamoto at Nintendo. And he kind of helped guide the sort of usability of the game.”

Cuthbert was paired up with Yoshio Sakamoto who would serve as the director on the Eclipse project. Sakamoto is perhaps best known as the producer of the 2D Metroid series including the critically acclaimed Metroid Dread which was released on Nintendo Switch in 2021. Sakamoto’s job would be to shape the incredible ambition and technical knowhow into a finished game, with that signature Nintendo polish.

“With the Nintendo touch, it kind of made it easier to play. We have things like guides that help the player know how to dock with buildings and stuff like that. And then added that sort of Nintendo humor to the game as well as some funny little secrets in there and stuff like that. But really the changes were to the missions suite. So kind of gave them a sort of story which has a little bit more of a Japanese feel to it. And so a few things of that sort of came from the Nintendo, or really the Japanese kind of mind. And then all the other stuff brought in from the original kind of British feel of the game, and it’s kind of an interesting blend of both, I think. So really, I mean, we just kind of fleshed out everything with Nintendo.”

As Eclipse grew into a full game, there was still one last change to make.

“Well, Eclipse was the original game name, it’s like the prototype name. So it’s kind of the thing that I thought up in the very initial stages of the game. It was never intended to be really actually called that, but I think maybe the Mindscape signing was probably for ‘Eclipse’. I don’t think they were interested in changing the name. But for Nintendo, obviously Nintendo put a lot more effort into making sure there aren’t any name clashes and stuff like that. So a whole bunch of names were put forward. I think Lunar Chase was one of the ones I also put forward for them when they were doing their name check and it’s the one that kind of came through that was okay. And so we gave it that title for a long time.”

The name Lunar Chase stuck with the project, to the point that the planned english release of the game, which eventually found its way online, still bears that original title. For this reason Lunar Chase is generally, to this day, still thought of as the unofficial western title for the game.

“But then about a month or two before release, suddenly Yamauchi (Hiroshi Yamauchi was the President of Nintendo from 1949-2002) after playing the game, he calls up Sakamoto at 8:00 a.m. or 7 a.m. in the morning, kind of woke him up he said, and basically said, ‘okay, this is fine, but you’ve got to call the game X’. And so then Sakamoto came in that morning and came to me, came to my desk and said like, ‘okay, Yamauchi called me directly and said, we’re calling the game X’. Okay, all right. And that was the name from there on.”

Despite never officially leaving Japan, X would go on to be regarded as one of the single most important games ever made. It spawned the creation of Star Fox and contributed to Nintendo’s shift in focus to 3D games. It helped launch the career of Dylan Cuthbert who would go on to work with both Nintendo and Sony, before starting his own company, Q-Games, in 2001. In 2010 Q-Games partnered with Nintendo to release X-Scape, a DSiWare sequel to the original X.

X itself has never been re-released or given an official release outside of Japan. With the closure of the 3DS eShop, the last digital shop to host DSiWare titles, X-Scape cannot be legally purchased.

“I’d like to see, specifically more people able to play X-Scape or X-Returns, as it’s called in Japan… It’s just a shame that not really enough people played it just because it was hard to access, being on the DSi. I’d like to see that somehow get resurrected somewhere, even if it’s like a remaster or something. There are a lot of very good DsiWare games. I would love for Nintendo to come up with a way to give people access to that catalog. We didn’t just make X-Scape on it. We also made Starship Defender and Reflect Missile (called Trajectile in some regions). And they’re all really good games, but just no one really got to see them because they’re on DSiWare. And so I’m hoping that Nintendo is going to do something about that at some point. And with X itself, I mean, obviously only the Japanese version can be played right now officially if you buy a cartridge and a very old Gameboy.”

While thanks to the efforts of Mark and Michelle Flitman along with the Video Game History Foundation, we’re able to gain new insights into the history of these games, the public’s legal access to them is borderline non-existent.

“When we’re going into these houses we never really know what to expect and a lot of that’s because you can’t suss that information out ahead of time.” Frank told me. “People don’t tend to know what’s historically important because they’re not historians. We go into these things going like okay this could be a total bust. Like he might just have a bunch of like final versions of his games and business cards. Or, in cases like this he has like kind of a holy relic of a very important game series. It keeps the job really interesting and honestly it’s more wins than than duds in this line of work. Especially in that era of video games a lot of material was made and scrapped and just kind of left around so there’s still a lot to discover. If you got a basement with this kind of thing you should probably get in touch”

As for Dylan he’d love to go back to revisit that world again one day.

“I’d love to make a sequel, you know? I mean, it took a long time to make the first sequel. It was like 20 years, I think since the original game came out is when we released the first sequel to the game. But maybe we can do that in a shorter time frame at some point. But it depends. It’s a bit of a niche game, but I think there are still a lot of people who would like that kind of game still. So I’d definitely like to have a shot at it at some point.”

For further exploration, the ROM data for Eclipse is available on The Internet Archive.

About The Author

John Rairdin is the director of NintendoWorldReport.com, one of the oldest Nintendo enthusiast press sites on the internet. He is an expert on the history of the Star Fox franchise and has produced multiple documentaries on the development of the series, including extensive interviews with its creators.

Special Thanks to Dylan Cuthbert, Mark Flitman, Michelle Flitman, Hollie Hughes, Robert Hughes, Kaytee Rairdin, Frank Cifaldi, Kelsey Lewin, and the staff of Nintendo World Report.