Today, the Video Game History Foundation and the Software Preservation Network published a major new study which shows that 87 percent of classic games released in the United States are out of print. The results are striking, and it proves that we need to rethink the commercial marketplace’s role in game preservation.

It’s a big study, and to help you digest it, we wrote this guide explaining the main points: Why we did it, how we did it, what we found, and why it matters.

Why did you do this study?

“Most classic games are no longer in print” might sound like an obvious statement for us to write a 40-page study about. And it is! The retrogaming community knows from experience that most games are no longer available. Anyone who’s tried to research old video games has probably run into a situation where they can’t get a copy of the game they’re studying. That’s the reality of the video game market.

However, this isn’t widely known outside the gaming community, and it’s not easy to prove. From the outside, it certainly doesn’t look like there’s a problem. You can fire up your Switch and get Super Mario Bros. and Pac-Man. You can buy a new copy of Final Fantasy VII for just about every platform. There’s certainly a market for classic game re-releases, and as far as the game industry is concerned, business is booming.

Why does it matter whether we know how many games are in print?

So there’s confusion about the state of the market for classic games. So what? That might not seem like a big deal, but it has big implications for game preservation and copyright reform.

Since 2015, libraries, museums, and archives in the United States have been petitioning the Copyright Office for new exemptions that would make it easier for them to preserve games and make those games available to researchers. Each time, game industry lobbyists have opposed these new exemptions. They’ve argued that there’s already an active, growing market for classic games, something that libraries would interfere with if they got their way.

It’s true that there’s more games being re-released than ever before. But then why does the gaming community believe that so few classic games are still available? What’s the real story here? If we want to have a productive conversation about game preservation, we need an accurate understanding of where things stand right now.

We conducted this study to settle the facts. It’s not enough just to have a hunch. We need hard data.

Where have all the games gone?

Our report explains why games aren’t in print, including technical issues, rights issues, low commercial value, and digital store shutdowns. If you’re not familiar with these underlying problems, read the “Obstacles to Game Availability” section of the report (p. 7–13) for a rundown of why you can’t just buy every video game.

How do you get “hard data” for this?

Our study has one major question: What percent of classic games are still in release?

We decided the best way to approach this was to take a big, random sample of all classic video games released in the U.S. and find out whether you can still get them. It’s hard to define exactly what a “classic game” is, but for the sake of this study, we looked at all games released before 2010, which is roughly the year when digital game distribution started to take off.

Our random list of 1,500 games was taken from MobyGames, a huge community-run database of video games. We wanted to use a single source for our data, and out of the databases we looked at, MobyGames had the most complete catalog of classic titles.

Wait, you studied all classic games? Isn’t that a little broad?

It is, and that was on purpose! But we realized it would be helpful to get some more targeted data too.

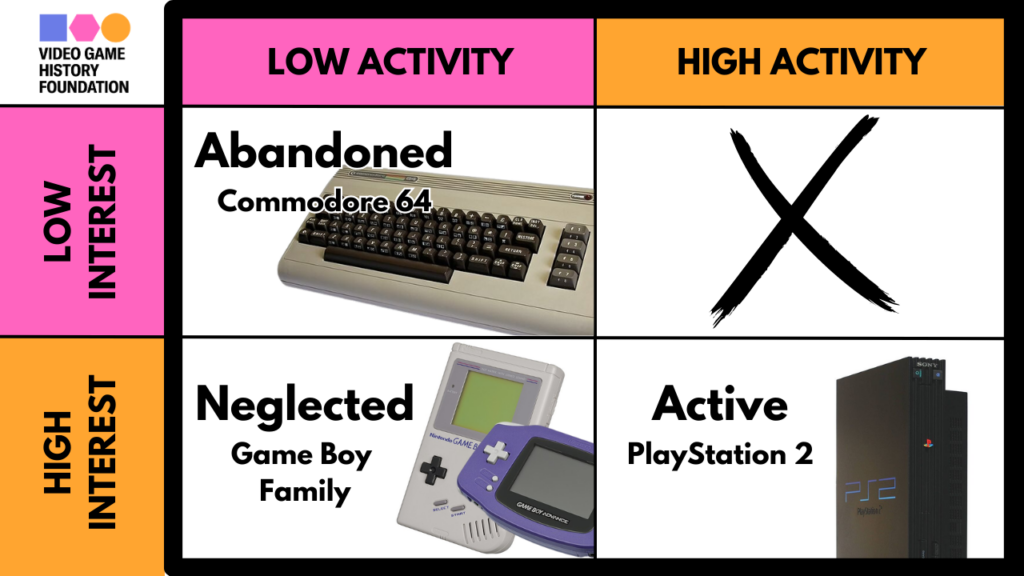

One of the biggest factors for whether a game is in print is the console it was originally released for. If a console is hard to emulate, or if there’s not much commercial interest in the platform, then there’s a good chance you can’t get many of those games today. To get a better idea of where different kinds of platforms stand, we looked at examples of three different game “ecosystems”:

- Abandoned ecosystems, with low commercial interest and few games available. For our example, we picked the Commodore 64.

- Neglected ecosystems, where there’s a lot of commercial interest but still not many games in print. We picked the Game Boy family, from the original Game Boy through the Game Boy Advance.

- Active ecosystems, where games for these platforms are being re-released all the time. We picked the PlayStation 2.

For most of these cases, we used the same method of grabbing a random sample from MobyGames. However, we decided to study every game in the Game Boy library. After the Nintendo’s 3DS and Wii U eShops were shut down in March 2023, the number of Game Boy games in print declined sharply, and we wanted to get the whole picture of how many Game Boy titles are actually still on the market. In this case, we checked additional data sources to make sure we included every single Game Boy game, including ones that were missing from MobyGames.

In total, our study looked at over 4,000 video games. Our team of volunteers from the Video Game History Foundation community and the University of Washington Information School spent nearly four months determining whether each game was in release, after which we double-checked their results. Our data is accurate through April 15, 2023, so if any games went in or out of print after that date, we didn’t capture it.

How did you decide if a game is in print?

To make our research as clear-cut as possible, we kept our results for each game to a simple “Yes” or “No.” Can you get it or not?

Sometimes it’s not so easy to tell! What if you can’t get the original version of the game, but you can get a remaster? Or a special edition? Or a remake? What if there’s content missing in the re-release? What if the controls are completely different?

We wanted to give publishers full credit for trying to re-release their games. We didn’t want to split hairs about, for instance, whether a remaster is technically a different game or not. It didn’t even matter if the re-releases were actually out yet, as long as they had been announced.

But we had to draw the line somewhere, so we came up with a litmus test: Is the version of the game that’s in print substantially different from the original? If so, they should be treated like different games.

For an example from the study, the 1987 interactive fiction game Jinxter by Magnetic Scrolls is available on a few different platforms as a “revived and enhanced” edition with new graphics and a more modern interface. Although it looks different than the original 1987 version, it’s still functionally the same text-based game. We decided they were not substantially different, and we counted this game as “Yes”!

On the other hand, the original 2005 version of Yakuza is substantially different from the remake, Yakuza Kiwami, which is currently in print. Although Yakuza Kiwami is extremely faithful to the original Yakuza game, it is a complete remake from the ground up and should be considered a separate title. Since the original Yakuza is no longer in print, we counted it as “No.”

But what about…

Once you start looking at different editions of games with different features, it gets tricky. If you want to get into the nitty gritty, we included more examples of what “substantially different” means in the full report under Appendix B: Discussion of Definitions (p. 39–42).

We also factored in whether a game was reasonably available. We didn’t count games that have only been re-released as expensive or limited-edition collector’s items, games that are only available as raw source code, or games that can only be purchased for defunct vintage game platforms. They needed to be as simple as possible for an average user to play.

For full transparency, we uploaded our complete results to the research repository Zenodo, along with detailed notes explaining how we made tough judgment calls. You can check our work if you want to!

Okay, but is this study actually scientific?

Yes! We wanted to do this right, so we made sure our methods were rigorous. We developed our research strategies with help from the Data Learning Center at the Department of Research Informatics and Publishing at Penn State University Libraries, along with the input from academic archivists and the experts on the Software Preservation Network’s Law & Policy Working Group.

What did you find out?

It’s bad, folks. It’s really bad. As we mentioned, our results show that only 13 percent of classic games released in the United States are still in print (with a margin of error of ±2.5 percent). But it gets worse!

The results were consistently low across every time period and platform we studied. Our abandoned ecosystem, the Commodore 64, clocked in at an abysmal 4.5%, while our active ecosystem, the PlayStation 2, only managed to make it to 12%. No five-year period examined by this study rose above 20% availability.

How bad is that?

For comparison, this is slightly above the availability of pre-World War II audio recordings (10 percent or less) and slightly below the survival rate of American silent films (14 percent). We’re talking about games from the ‘80s, ‘90s, and 2000s, and they’re in just as bad shape as music and movies from back when Calvin Coolidge was president.

Classic game availability, by the years

What about Game Boy?

We said we wanted to take a close look at the entire Game Boy family, and with good reason! From our results, as of April 2023, only 5.87% of Game Boy games were still in print. That’s a pretty bad number, but it gets even worse when you consider that an additional 6.5% of Game Boy games used to be in print on the 3DS and Wii U eShops before they closed. This means that when the eShops were shut down, the majority of all Game Boy games on the market fell out of release!

Does this really matter? I can still buy the games that I want.

Some of the most popular classic games are part of that 13 percent that remains in print. If those are the games that people most want to play, what’s the problem here?

The problem is that video game history is more than just the bestsellers. If we want to understand and appreciate the history of video games, we need more than a curated list of the games that publishers decide have commercial value.

In fact, we found evidence that these numbers directly impact games that are interesting to researchers and historians. The era before the 1983–1984 video game industry crash is like the silent film era for video games, a period when the rules and vocabulary of games were first being established. Naturally, historians would want to be able to play these games, but our study found that less than 3 percent of games released before 1985 are still in print!

The commercial market has its own interests, and they don’t align with what researchers need!

Game availability, by ecosystem

Commodore 64

PlayStation 2

Game Boy Family

This is going to keep improving as more games get re-released, right?

We wish! During our research, we noticed some worrying patterns that suggest this is actually going to get worse over time.

Obviously, when digital game stores and services shut down, that means games will go out of print. The 3DS and Wii U eShop closures are big examples. An estimated 1,000 unique games fell out of release when those stores closed. Microsoft and Sony have suggested that shutdowns are also coming for the Xbox 360 Marketplace and PlayStation 3 and Vita stores, respectively.

But it’s not just that game stores are closing. We also found that classic games are sometimes only re-released for a single platform, meaning if that platform goes down, those classic games will disappear too. The worst offender we spotted is the Commodore 64: Most classic Commodore 64 games are only available through a single service, Antstream Arcade. If Antstream shut down, the availability rate for Commodore 64 games would plummet to an apocalyptically low 0.75%.

There are many advantages to digital games. Digital distribution makes it much, much easier to re-release classic games widely and at a low price. But digital stores and services are volatile by nature. Just because a game gets re-released once doesn’t mean it will stay available forever.

Whatever, I can still pirate these games.

It’s true that piracy is often the easiest way—or the only way!—to play many classic games. The alternative is to spend hundreds or thousands of dollars on vintage games and specialty hardware, or to arrange for weeks of travel to visit a library’s game collection in person. Those are unreasonable asks. It’s no wonder that even academic researchers rely on abandonware sites to get access to old games.

We’re lucky that these games aren’t entirely lost to time yet, but we need to do better than that. We shouldn’t accept that we have to forfeit video game history entirely to the realm of legally murky websites and secret torrents known only to the most diehard of fans.

So what do we do about this?

Ultimately, we shouldn’t expect the marketplace to solve this one. Like any media business, the game industry has its own commercial interests, and we can’t expect them to make history their top priority and preserve every single video game.

You know who can work on that? Libraries and archives. And they need more tools to get the job done. As we talked about, there are improvements that can be made in copyright law to make it easier for libraries and archives to preserve video games and share them with researchers, but we avoided proposing any specific solutions in this report. We’re leaving it up to the policy experts to make their own recommendations.

What we’re asking with this report is for the game industry to acknowledge that most classic games are out of print, and that the commercial market alone can’t solve this. If we want to move this conversation forward, we need to agree on the facts. We’ve rigorously proven that less than one-fifth of all classic video games are still in print—and that’s not enough for what we need.

If we can agree that there’s work to be done here, that’s the first step towards fixing the future.

Some thoughts from VGHF and SPN

We wanted to share some additional thoughts on why this study matters, so we rounded up some words from VGHF’s co-directors and our friends at the Software Preservation Network.

I hope this study wakes people up. For years, we’ve known that the availability of classic video games in a legal, safe way has been dire, but no one has ever put a number to that. The results are worse than probably any other medium.

Frank Cifaldi, co-director, Video Game History Foundation

This is the moment to sound the alarms for both the video game industry and the preservation world. The study proves that it’s worse than it looks – for every Mario game that’s available, there’s hundreds of less popular games that are critically endangered. Our goal is that by exposing just how dire the state of game availability is, we can drive changes to our copyright laws that will make video game preservation stronger, and able to take on the challenges of the future.

Kelsey Lewin, co-director, Video Game History Foundation

This study is an extraordinarily valuable resource for me and the communities I advise. Previous studies on sound recordings, films, and books have shown that regardless of rights holder rhetoric about digital distribution and the ‘long tail,’ the commercial market continues to focus on new releases. This leaves libraries and archives as the only reliable long-term stewards of cultural heritage.

This study shows that almost all video games from the format’s earliest days are unavailable, that the vast majority of video games are out-of-commerce less than a decade after they are published, and that entire ecosystems can disappear overnight. But the law tells us that all these games will be in-copyright for almost a century! That disconnect reveals the urgency for groups like the Software Preservation Network and the Video Game History Foundation to understand their legal rights, to advocate for balanced copyright rules, and to act with courage to preserve our shared digital culture. It should also make clear to policymakers that these institutions deserve more and better tools to do their jobs, because the market will not preserve our history. That’s not the market’s job. If we lose access to our digital cultural heritage, it’s not a market failure; it’s a policy failure.

Brandon Butler, Director of Information Policy, University of Virginia Library, and Law and Policy Advisor, Software Preservation Network

Special thanks to our volunteers:

A previous version of this article misstated that cultural heritage institutions first supported DMCA exemptions for video game preservation in 2012, rather than 2015. The error has been corrected.