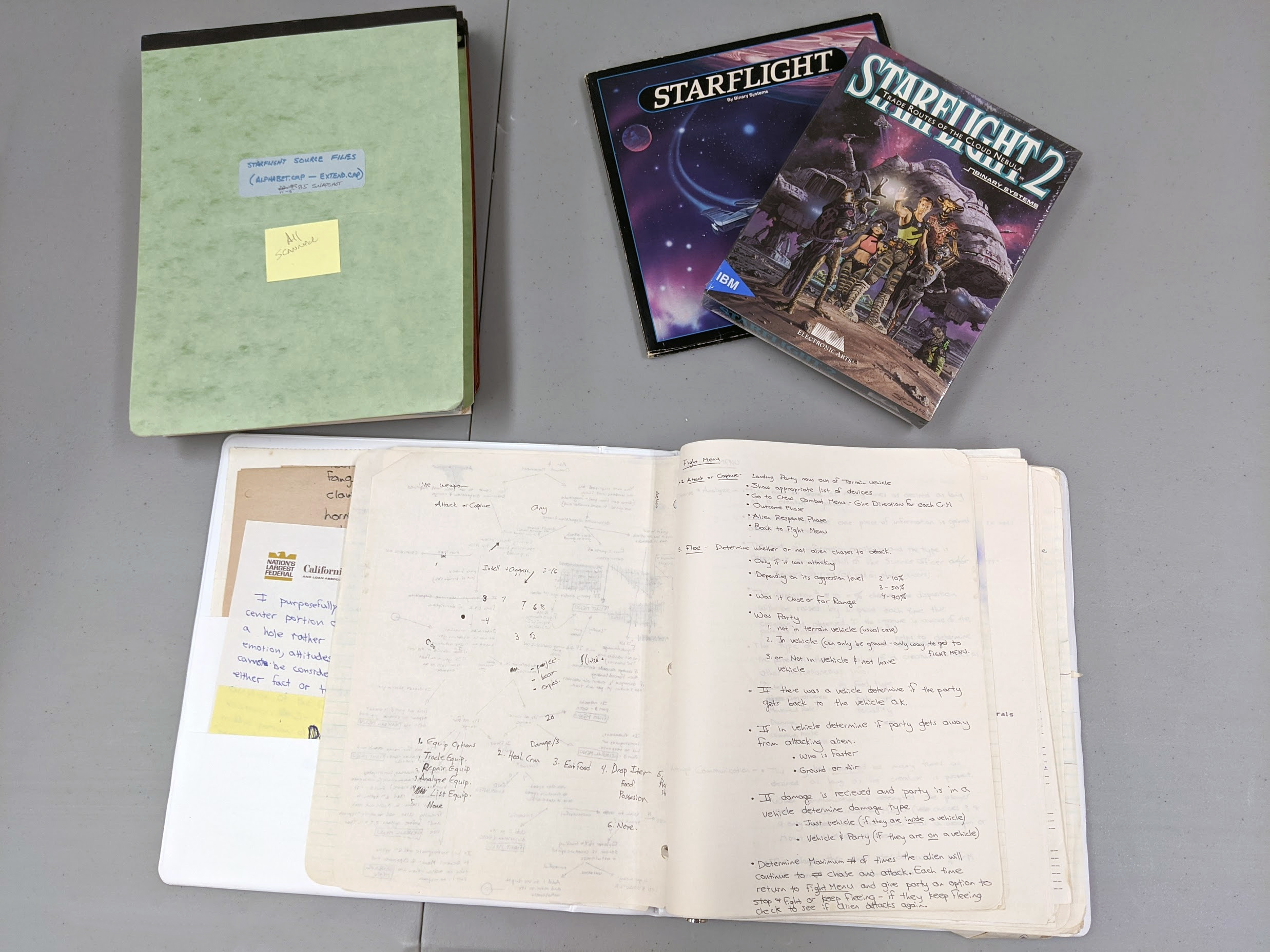

Video game source code and other source materials are inarguably the best resources for those studying how a game was made. And yet the availability of these materials is scarce at best, with few examples available online and even fewer in institutional archives. Worse, historical source code from the earliest days of the medium is being lost by the day.

We’d like to change that. Today, we’re announcing what we’re calling our Video Game Source Project, the VGHF’s most ambitious initiative to date. It’s a wake-up call to preserve this endangered resource, a call to arms to locate it and make it accessible, and a forward-thinking vision of a world in which using this material as an educational resource is commonplace.

What is video game source?

Simply put, when we refer to a video game’s “source”, we mean the raw materials used in its production, including but not limited to source code, art, documentation, and records of correspondence (think emails, letters, or, as is the case for some repositories in our archives, faxes).

In the video game industry, the preservation and documentation of source is what allows a game to survive past its initial release. Remastering a game, or even porting it to another platform, is nearly impossible without it.

In the hands of an historian, a properly archived source repository is the next best thing to time travel.

Why is source so inaccessible?

We’ve identified three key factors for video game source being inaccessible: trade secrecy, entropy, and a lack of awareness.

Simply put, source is the intellectual property of its owner, and in almost all cases, is seen as a trade secret within the industry. If competitors had access to a game’s source, aspects of the game could easily be cloned. Unfortunately, there is no internal “statute of limitations” for video game archives, so an out-of-print game from 30 years ago is often as closely guarded as a game that’s currently for sale.

This is also how entropy claims its victims. Source material that is past its prime is often forgotten or, worse, destroyed, since long-term archival practices within the commercial industry are incredibly rare. We have lost countless archives due to office moves, closures, accidents, theft, and forgotten knowledge — there might not be anyone left on staff who remembers where the old files are, or how to retrieve them.

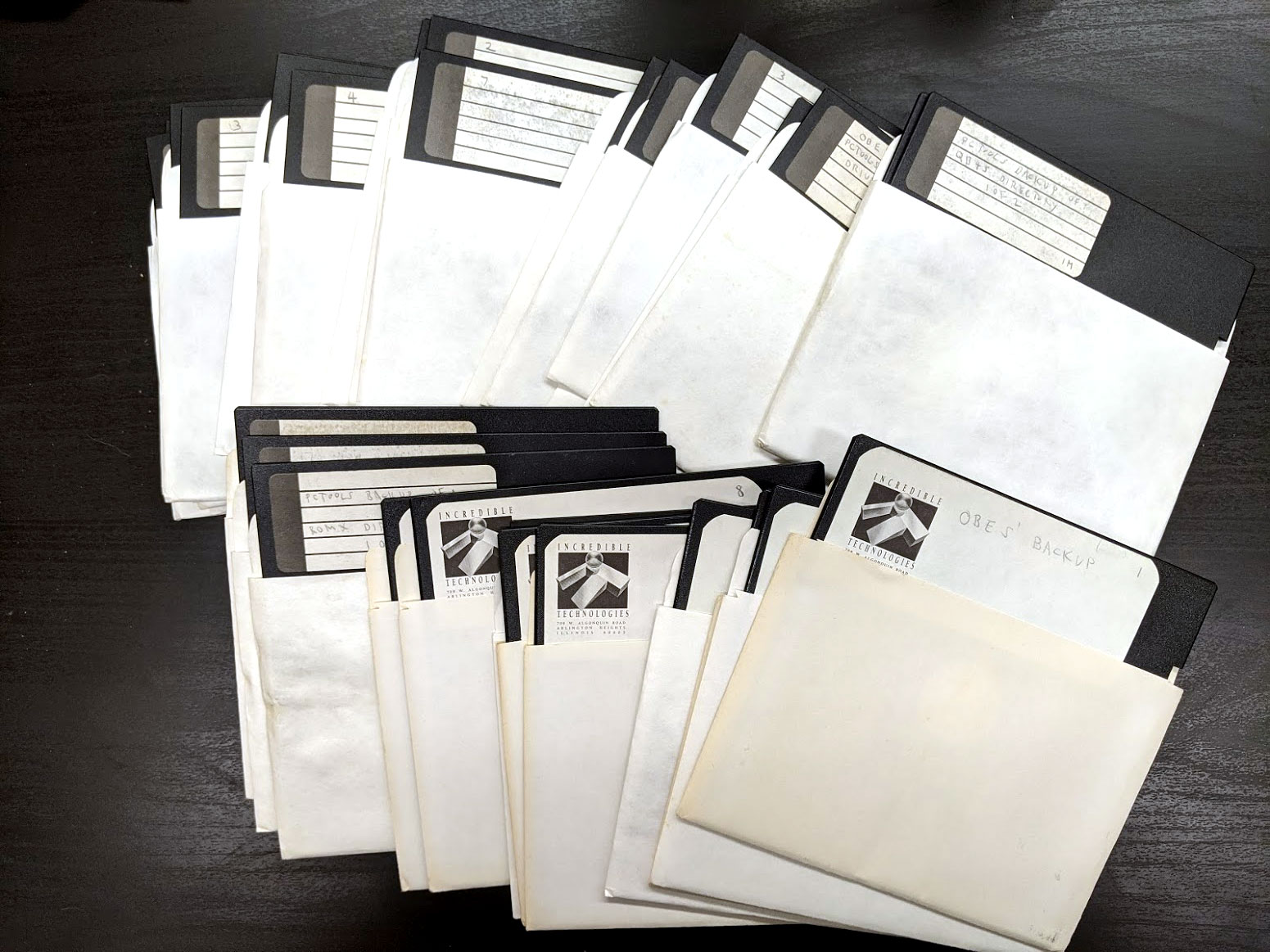

And finally, there just hasn’t been a coordinated awareness campaign for video game source until now. Many developers we’ve spoken to have been surprised to learn that there is historical interest in this material, which is often sitting forgotten on floppy disks or other deprecated media in desperate need of backing up.

We want to preserve as much source as we can, and to normalize its educational use.

And to get there, we must identify and solve the issues that are preventing this from happening. To that end, we’ve begun to establish an advisory committee consisting of people not only from the commercial video game industry, but from academia and other non-profit institutions similar to ours.

We’re also leading by example, producing content that demonstrates the power of video game source material in an historian’s hands. We’ve deconstructed a 16-bit classic, brought a lost game back from the dead, and demonstrated the hidden history found in an unfinished prototype.

We’re also proud to announce an event on October 30, celebrating the 30th anniversary of The Secret of Monkey Island by looking through its source material with the game’s creator, Ron Gilbert. Tickets are available here.

Source is the future of video game preservation.

One day, access to source through libraries and institutions will be as common as author manuscripts and film production archives are today. We’ve got a long way to go until we get there, but that journey starts now.

Be a part of the conversation!

If you’d like to get in touch about the project, or if you have material you’d like help conserving, let’s talk! Email us at sourcecode@gamehistory.org.