In the wake of the success of SimCity 2000, Maxis, the creators of SimCity, tried to capitalize on the game’s popularity with SimCopter — a helicopter simulation that put players in the role of an emergency worker who flies around the city breaking up traffic jams, putting out fires, and other tasks to keep the city running. But the game’s most notable feature wasn’t what you did. It was where you did it! SimCopter could import save files from SimCity 2000, letting players explore their cities from a whole new perspective.

SimCopter wasn’t a big hit for Maxis, but its add-on functionality with SimCity 2000 made it one of the most unique titles in Maxis’ catalog. Maybe it shouldn’t be surprising that Maxis tried to bring it to another platform.

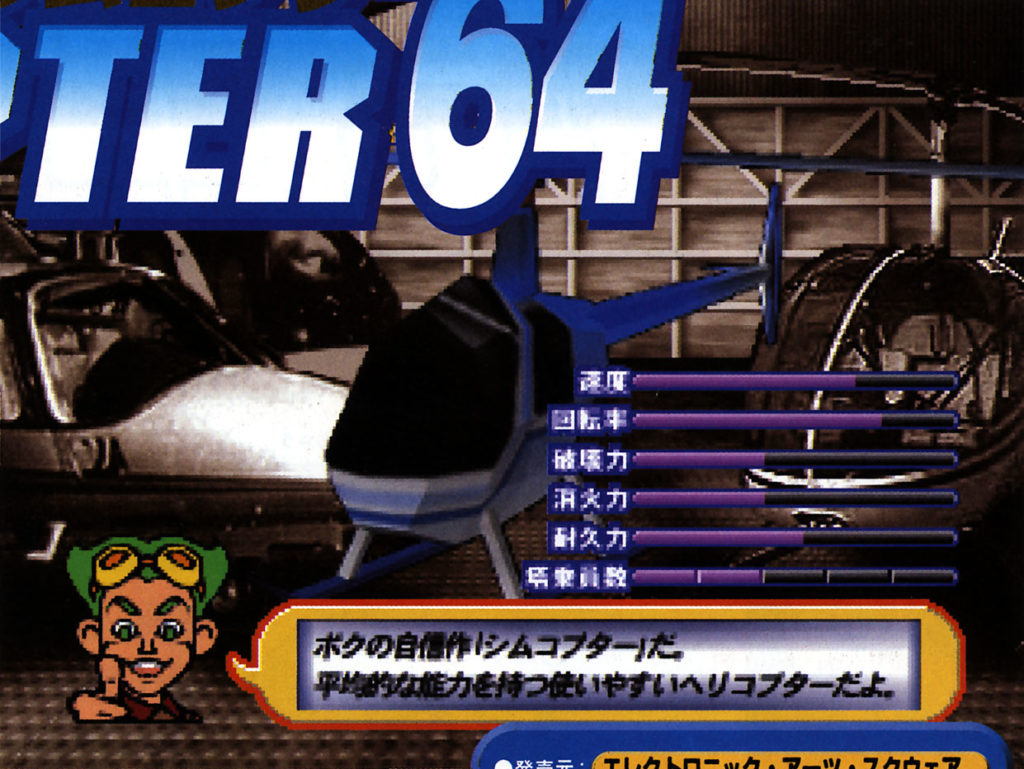

At E3 1997, Maxis quietly unveiled SimCopter 64, a re-imagining of SimCopter for the recently launched Nintendo 64 console. Much like the PC version of SimCopter, the game would have imported save files from SimCity, in this case the upcoming SimCity 64 by HAL Laboratory for the Nintendo 64DD. But just as quietly as it was announced, the game was silently canceled a few years later. Apart from a few press blurbs and blurry magazine scans, little was known about the Nintendo 64 version of SimCopter, until now!

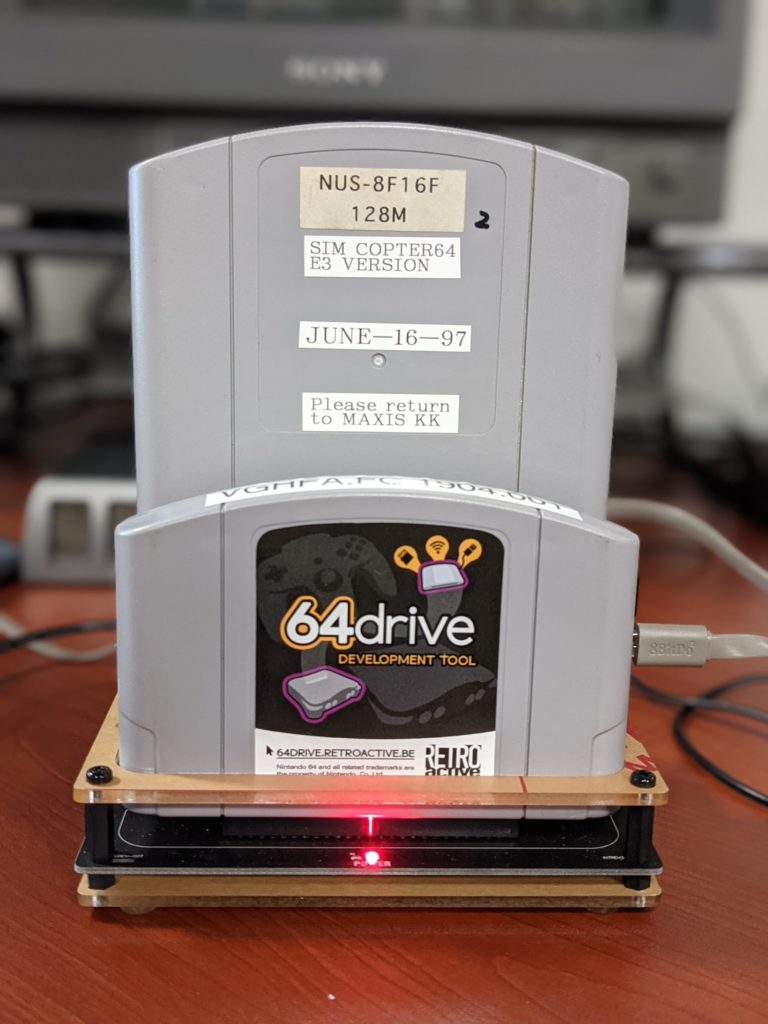

The Video Game History Foundation was recently donated a pre-alpha development build of SimCopter 64 from the game’s premiere at E3 1997, dated June 16, 1997. Although this version of the game is very early and nowhere near completion, we wanted to go deep to shed some light on its development. After digging far and wide, combing through magazines, and talking with former Maxis staff, this turned out to be a more complicated story than we expected. It’s a story about game publishers vying for a bigger stake in a growing industry, and a wild-card game they thought might be their ticket.

This is everything we know about SimCopter 64 — and why it was canceled.

Before we get started…

Your generous donations are what keep us going! We are a 501(c)3 charity dedicated to preserving and teaching the history of video games. If you’re able, please consider becoming a sustaining member today, either by credit card, Paypal, or better yet, by joining our Patreon community!

What’s the story here?

Before we even fire up this copy of SimCopter 64, the cartridge itself can tell us something. In addition to noting the date of this build, the label on the front of the extra-long development cartridge also says, “Please return to Maxis KK.”

So what does that mean? While it may not be clear to English speakers, Maxis K.K. is short for Maxis Kabushiki Kaisha (マクシス株式会社), which was the name of Maxis’ little-known subsidiary studio in Tokyo, Japan. When SimCopter 64 resurfaced earlier this year, there was some speculation that because of its anticipated cross-functionality with SimCity 64, the game may have been developed by HAL Laboratory. Believe it or not, SimCopter 64 was being created by Maxis themselves!

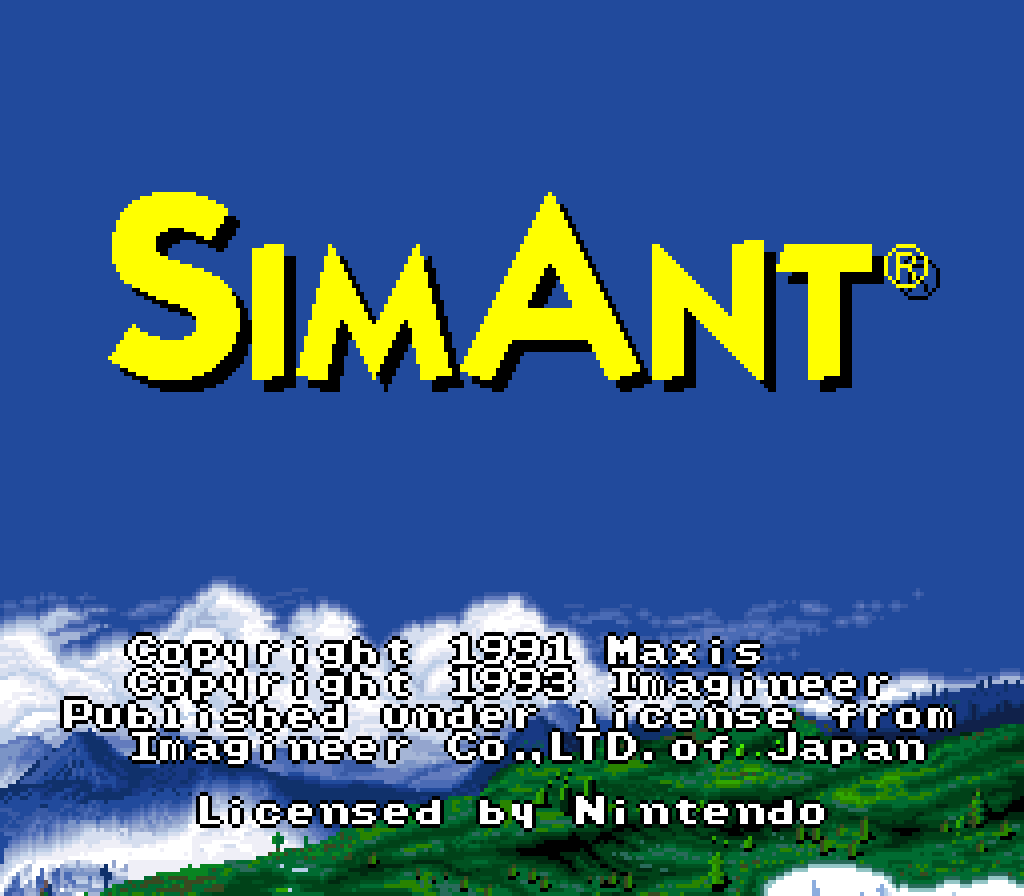

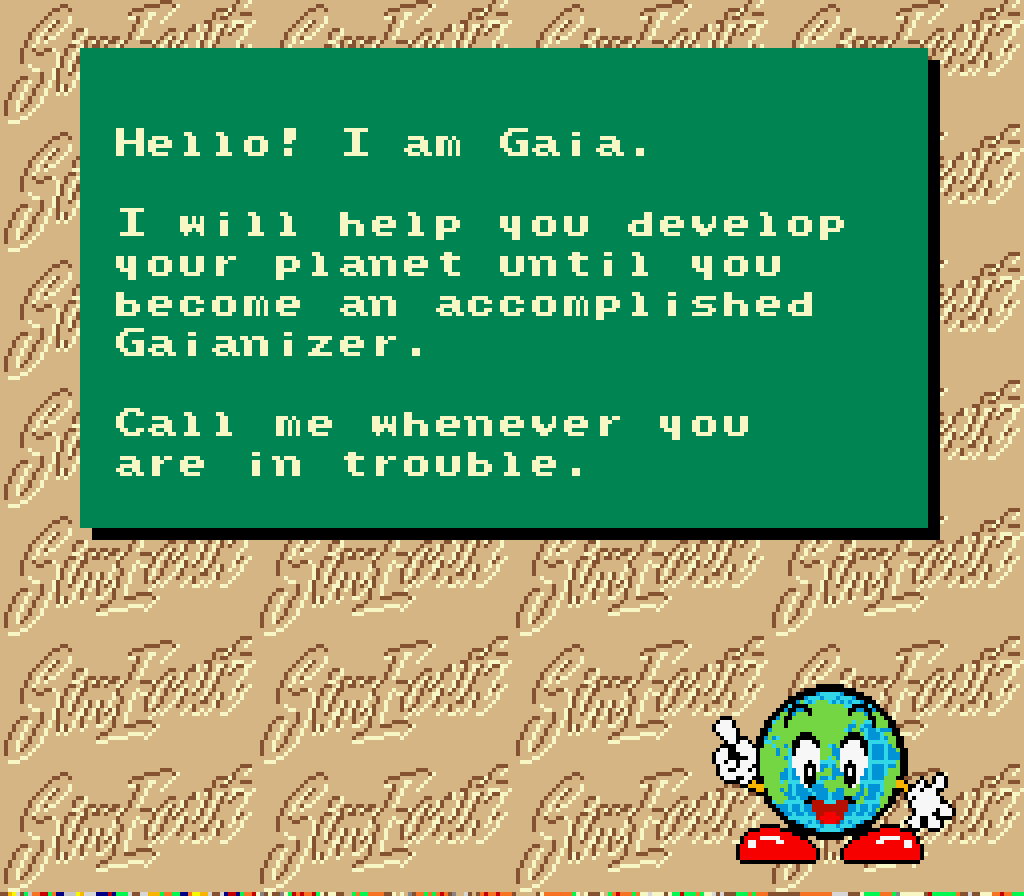

Despite being based out of California, Maxis was no stranger to working in Japan. For several years before SimCopter 64 came along, Maxis ran a regional sales and marketing office in Tokyo. They also had a relationship with Imagineer, a Tokyo-based publisher that handled the Japanese releases of Maxis games going all the way back to the original SimCity. Imagineer also oversaw the Super Nintendo adaptations of SimAnt and SimEarth, which gave their simulation games a cutesy, console-friendly makeover.

But in 1995, Maxis’ ambitions grew. The company had gone public on the stock market, and now they wanted to cut out the middleman and publish more of their games themselves, with a focus on console games and international distribution. With Maxis’ history in Japan, the Japanese console market was a prime target for their new strategy. That’s why, in April 1996, they expanded their Tokyo operation into a full-blown subsidiary studio, Maxis K.K.

To lead the new development studio, Maxis tapped Akifumi “Aki” Kodama, the former executive vice president of Imagineer who had orchestrated the relationship between the two companies. Kodama was the perfect person for the job: not only did he already have industry connections that would make it easier to start self-publishing on Nintendo platforms in Japan, but going back as far as he did with Maxis, he must have known exactly what he was signing up for.

Basically, Maxis was building their own Imagineer.

Like Imagineer, Maxis K.K. handled the Japanese localization and publishing for several Maxis titles, like SimTunes and the original PC version of SimCopter. After Electronic Arts acquired Maxis in 1997, they kept the Japanese arm of the company running until at least 2009, likely working on localization for other Maxis titles like The Sims. But their biggest project seems to have been SimCopter 64, an ambitious attempt to bring SimCopter to Nintendo’s new 3D console.

Despite the uniqueness of SimCopter, it’s not obvious why Maxis wanted to port this particular game to the Nintendo 64 — especially after the bad press SimCopter generated for Maxis as a result of the unauthorized “himbo” easter egg (which is far outside the scope of this article but is worth learning about if you haven’t before).

For Maxis, it was all about expanding into new markets. As Maxis CEO Sam Poole explained in 1997, the company wanted to develop more action games because they attracted a different audience than the people who were playing their simulation games. In particular, since they wanted to crack the lucrative console market, that practically demanded at the time that they focus on faster-paced games than they were usually known for making.

Whether or not that was a good strategy for Maxis is up for debate. But if that was their priority, then a re-imagined SimCopter fit the bill. Jeffrey J. Feil, who served as assistant producer for SimCopter 64 under Electronic Arts, remembers that SimCopter was an ideal candidate for a console game because it was one of the more action-oriented titles that Maxis already had in their portfolio. Flying a helicopter translates much more easily to a controller with a joystick than the interface-heavy games that Maxis specialized in. (If you’ve ever played one of the console ports of SimCity 2000, you know how awkward that sort of conversion can be!)

Feil explains to the Video Game History Foundation that the development of SimCopter 64 was carried out mostly independently by Maxis K.K. in Japan. Over stateside, Feil recalls that the production was supervised by Maxis’ Action Sports Group, an internal team that had been set up in the waning years of the company to manage their non-simulation game output, then under Electronic Arts was repurposed as a secondary production unit for smaller EA titles such as Moto Racer. The crew assigned to work on SimCopter 64 was small; the only other person Feil remembers working with was EA producer Dave Davis, who led the project.

Every two weeks, the Tokyo studio would send a development cartridge to Maxis’ offices in Walnut Creek, California, and Feil would do some quality assurance work, testing recently added features to make sure the game was on track and passing along feedback. But apart from this periodic oversight, Maxis K.K. seems to have developed the game largely on their own.

Based on an unused texture discovered in the E3 1997 demo, the earliest known build date for SimCopter 64 was April 11, 1997, meaning development likely started in early 1997 or late 1996 after the PC release of SimCopter. It may have been in production for only a few months before it was shown off for the first time.

Maxis announced SimCopter 64 in May that year, shortly before the game’s first public appearance at E3 1997. From Maxis’ description, it sounds like their original vision was for the game to be a fairly direct port of SimCopter for PC. And that’s exactly what we found in the E3 demo.

Analyzing the E3 1997 build

E3 1997 was a big show for Maxis, but not because of SimCopter 64. Just two weeks prior, Electronic Arts announced they were acquiring Maxis for $125 million in stock. Whether the timing was intentional or not, E3 became Maxis’ chance to show why they were worth what EA was paying.

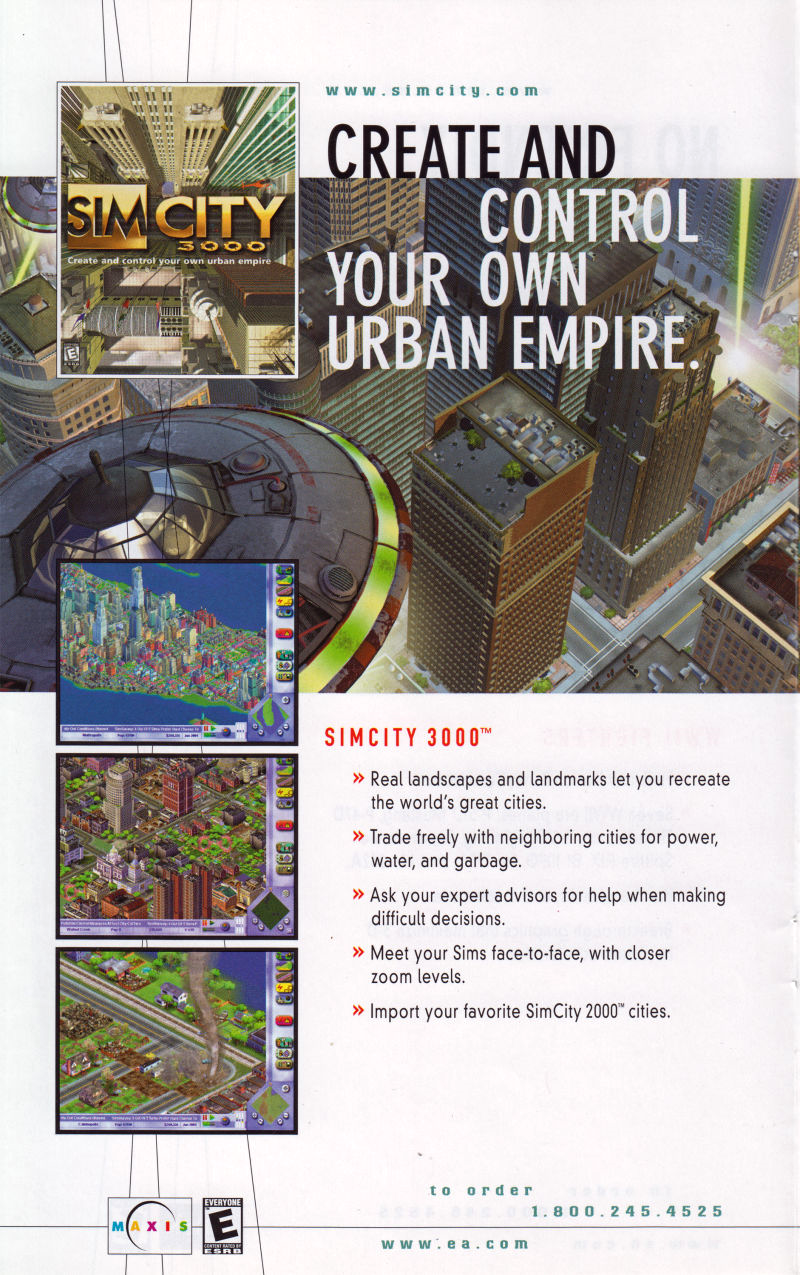

The main event that year was SimCity 3000, the third entry in the blockbuster SimCity franchise, which Maxis revealed on the first day of E3. Based on surviving footage from a promotional video tape from E3 1997, SimCity 3000 absolutely dominated the Maxis booth, which was sandwiched between GT Interactive, Ubisoft, and Activision on the show floor.

To the extent that SimCopter 64 had a presence at the Maxis booth, the promotional video shows what appears to be a single station for SimCopter, shunted off to the corner. It wasn’t even mentioned in Maxis’ E3 press kit.

“SimCity 3000 was the priority and the reason why EA was buying us,” recalls Patrick Buechner, who was public relations manager for Maxis during E3 1997, “so it makes sense that other games, especially ones in early development [wouldn’t] get a big showing.”

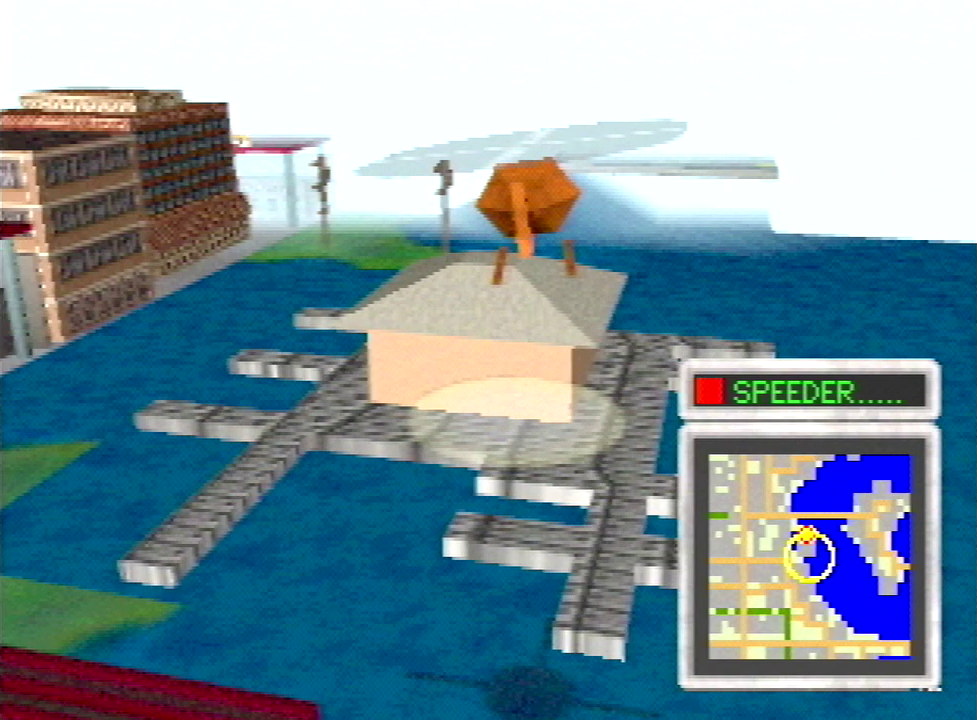

Looking at the build obtained by the Video Game History Foundation, it’s clear why Maxis didn’t focus on the game. At this point, SimCopter 64 was very, very early in development. The gameplay closely follows the PC version: You’re a helicopter pilot, and from time to time, a dispatcher will ask you to intervene in random events around the city, like traffic jams and speeding cars.

However, only the most rudimentary features of the game are implemented so far. There are no collision physics, meaning that the helicopter can fly through buildings. Your pilot can exit the helicopter and walk around, but cars will drive right through them. There are some characters aimlessly wandering around town, but there’s no way to interact with them.

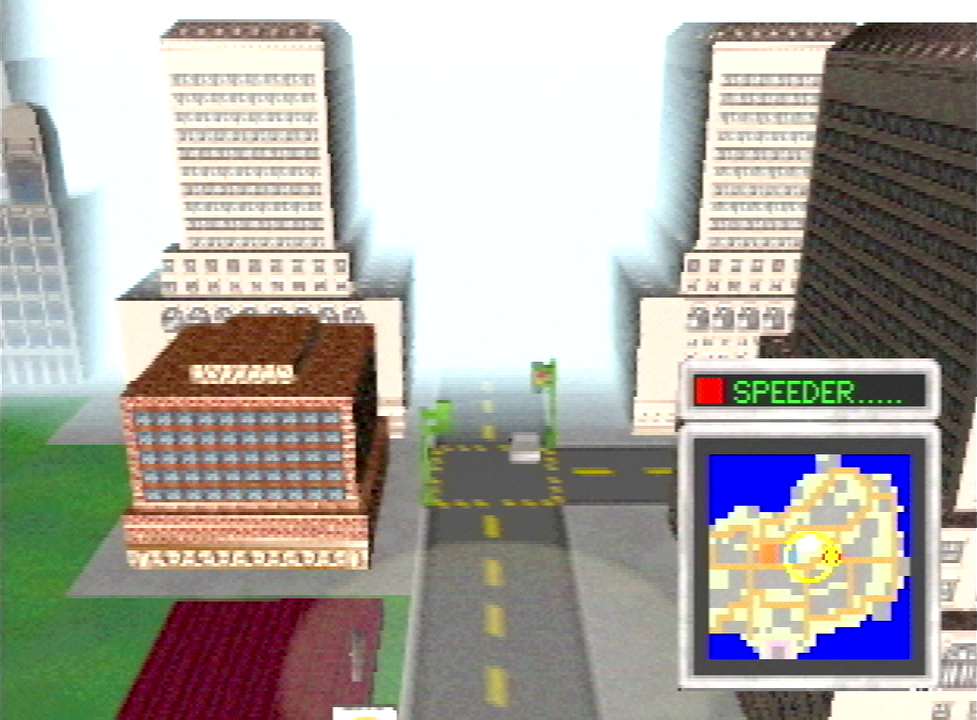

Most noticeably, the world of SimCopter 64 is shrouded in a thick layer of fog, which would become an unfortunate trademark of Nintendo 64 games. Rendering an entire city was a tall task for the console, and the compromise to get the game to run on the hardware is unignorable. The low render distance makes it difficult to navigate the city at high altitudes and spoils the fantasy of flying a helicopter.

Ironically, these were the same problems that plagued the original real-time 3D version of SimCity 3000 that overshadowed SimCopter 64 at E3 that year. 3D hardware was just not at the point where it was ready to render an entire city at the speed and level of detail that Maxis needed to bring their worlds to life.

With all these compromises and missing features, this build of SimCopter 64 is clearly still a prototype. The video game community likes to call any development version of a video game a “prototype,” but make no mistake, this is a capital-p Prototype. It’d almost be more accurate to call it a proof of concept rather than a functional game.

The video footage of the Maxis booth seems to show a person pointing at the screen during gameplay, suggesting that SimCopter 64 may have been shown as a scripted, hands-off demo. This would have been the only appropriate way to present a game so early in development that it didn’t even have collision physics yet. Really, it’s surprising that Maxis would have publicly shown this version of the game in any capacity.

(Theatre Square is loosely based on the real Theatre Square in Orinda, CA, where Maxis was headquartered from 1991–95.)

Despite the incomplete state of the build, it’s still identifiable as SimCopter running on a Nintendo console. The visuals mimic the original SimCopter with more saturated colors and cutesy flourishes, like the two-dimensional sprite-based civilians walking around town, or the big icons on the roofs of police stations, fire departments, and hospitals. Traffic seems to be dynamically generated. The developers have made a good effort at mapping the sprawling control scheme of SimCopter to a Nintendo 64 controller, using the R button as a multi-use button for in-game events, like using the helicopter’s loudspeaker to shout down at traffic. It still has Jerry Martin’s pulsating menu soundtrack, and even though there are only two emergency events so far in this version of the game, it’s still the same voice of the dispatcher from the PC version alerting you over the radio.

This version even includes all thirty cities from the original SimCopter, plus an additional debug city. They’re in varying states of functionality in this build; attempting to load some of the bigger cities like River Valley, Whattheheck, and Metropolis immediately crashes the game, possibly because of the memory limitations on the Nintendo 64 compared to the development environments Maxis K.K. was using. Regardless, all thirty cities are represented here.

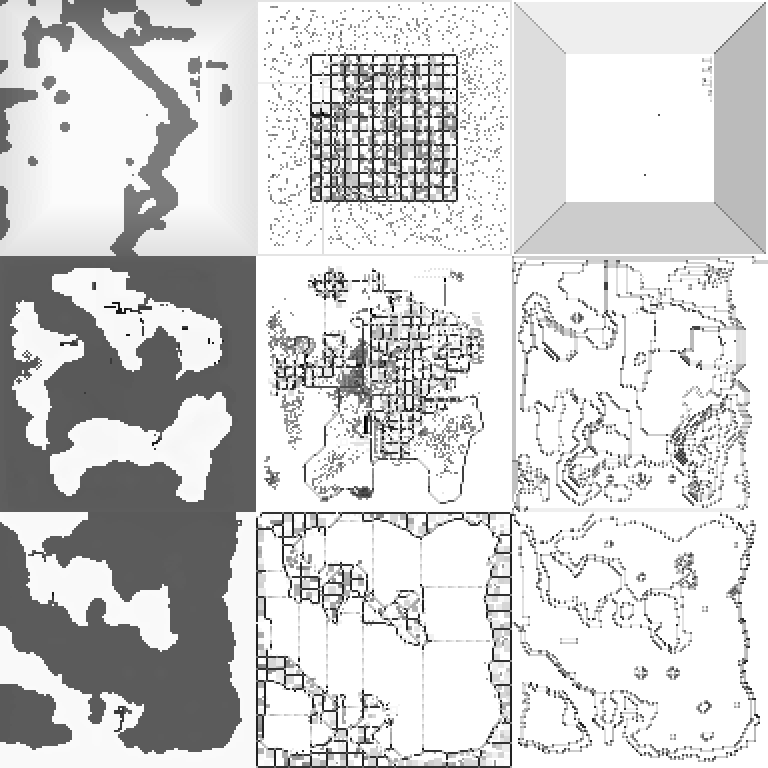

Looking more closely at how the cities are stored in the ROM file, SimCopter 64 seems to use the same data storage format as SimCity 2000 save files. The 128×128 city grid is broken into three pieces: a 32kb chunk describing terrain altitude and water level, followed by two 16kb chunks describing the shape of the terrain and the buildings (or trees) placed on top. While the terrain shape and building chunks are compressed in SimCity 2000 save files, they’re left uncompressed in the E3 build of SimCopter 64, maybe for ease of use while the developers were still working with a larger-than-retail development cartridge and didn’t have to worry as much about compression.

The appearance of a hidden dry riverbed in both the console and PC versions of Hidden Valley gives credence to the idea that the map data in SimCopter 64 was taken directly from the PC version. This might be the closest the Video Game History Foundation will come to literal archaeology.

Comparing just the uncompressed terrain data from both versions of SimCopter, the cities seem to be identical. This was most obvious when looking at Hidden Valley, a bizarre city set at the bottom of a square, bowl-like canyon. When visualizing the city data using Texture64, a texture-viewing tool for Nintendo 64 games, you can see a remnant of a riverbed running across the otherwise dry city; this corresponds to bits 9-10 in the terrain data, which seem to be related to the city’s water table, possibly for simulating floods. This data isn’t visible in-game and would only have been created by the terrain generator in SimCity 2000.

The invisible riverbed data showing up in the PC version of Hidden Valley makes sense, because the city probably would have been created in SimCity 2000. The fact that it also shows up in the console version tells us that the cities in this build of SimCopter 64 were taken directly out of the original SimCopter.

However, just because a city worked in SimCopter on the PC didn’t necessarily mean it would work here. While the game runs at a consistent (if low) framerate on original hardware, the crushing fog density and visual pop-in shows that getting this game to run well on the Nintendo 64 wasn’t going to be as simple as copying and pasting whole cities.

Speaking of copying and pasting, that’s not the only content lifted from other Maxis games! On closer inspection, some character sprites in this build of SimCopter 64 — particularly children — were borrowed from Maxis’ 1995 PC game SimTown! It makes sense that if SimCopter 64 was still very early in development, they would’ve used assets from an existing project as placeholders.

Exploring the ROM file reveals a bunch of additional unused character graphics in the same style. Of particular note is a rough, early sprite of the player’s pilot character, which appears to be a stretched-out version of the boy from SimTown, wearing a new outfit but still walking with the same awkward posture. The pilot and civilian graphics used in this build of SimCopter 64 have a completely different art style, so it stands to reason that these placeholder SimTown-based sprites were being replaced as new art was created.

But the most interesting thing about the unused sprites is that they hint at other concepts from SimCopter that hadn’t yet made it into the game. There are graphics for different types of civilians who don’t appear in this build, like a medic character, who would presumably be used for medical emergency missions like in the original SimCopter, as well as a speech balloon for civilians who would’ve interacted with your pilot. There’s a few unused sprites for the generic civilian character too, including a few where they appear to be falling down, also possibly related to medical emergencies.

(Understandably, there’s not a himbo in sight.)

Compared to known later builds of SimCopter 64, the E3 1997 build is, more or less, a straight adaptation of the PC version of SimCopter. But even this early in the project, it seems like SimCopter was going to be challenging to adapt for consoles, especially for a team that might have been working with Nintendo 64 development for the first time.

We reached out to Brian Conrad, who served as technical director at Maxis and publishing director for the Sim game division, for his recollections about SimCopter 64. Conrad oversaw several of the console ports of Maxis titles, and although he left the company during the early stages of SimCopter 64 and doesn’t recall working on the project, he tells us he’s skeptical that a straight port of SimCopter was ever viable. “You couldn’t put that game on a cartridge,” Conrad says. “Trying to stuff SimCity 2000 on a [PlayStation 1] was tough enough and it didn’t turn out well.”

That might be one reason why the game changed so radically over the next few months.

These screenshots were taken from the Italian game magazines Mega Console and Consoles+.[1] Since several game magazines used the same off-monitor screenshots, the screens may have originated from another source, like a Japanese publication that covered the event.

Thanks to Nintendo64EVER and Unseen64 contributor Celine for locating these screenshots, and thanks to Internet Archive uploader Overwatch 1579 for sharing high-quality scans of Consoles+ issues 72 and 79, originally scanned by Mimix.

SimCopter 64, take two

SimCopter 64 wasn’t working.

The next time SimCopter 64 was shown off, it was at Nintendo’s Space World expo in Japan in November 1997. While the new build looked similar to the E3 demo, it was more polished and feature-complete. Impressions were positive if vague, with Computer and Video Games magazine saying it was “already […] looking much more solid and convincing than the PC original.”

However, they also noted that they weren’t actually shown a live demo. Several publications reported that SimCopter 64 was only shown off at Space World as part of a video montage, despite having a demo at E3 earlier that year. The reason it wasn’t ready for prime time, it seems, was that even with the additional time in development, it just wasn’t a compelling game.

When Maxis originally announced SimCopter 64 in May 1997, their vision for the game sounded narrow, even stilted, with their press representative promising a game that “blends budget management with arcade-like vehicle control.” While that might be accurate to the original SimCopter, it wasn’t going to fly on the Nintendo 64.

“I remember it was very difficult to make SimCopter a [console] game, because SimCopter had no goal and it is just flying over a virtual city, just like another flight simulator,” former Maxis K.K. president Aki Kodama tells us. “So it was rather boring and not fun to play at all.” Maxis’ style of open-ended software toy might have worked on computers, but it didn’t make as much sense on a console where you’re competing against Super Mario 64.

The solution was to retool the game to make it even more console-friendly — even if it meant abandoning the original premise.

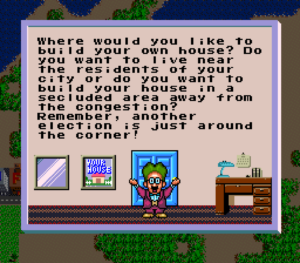

Think back to SimCity for the Super Nintendo. Even though it’s practically the same game as the original SimCity, Nintendo’s version added a stronger sense of linear progression. Whenever your city got to a certain size, Dr. Wright would pop up to celebrate, and the background music would change to reflect the next stage of your city’s development. What would the SimCopter version of that look like? Could you give the gameplay a sense of direction?

Over the next year, SimCopter 64 started to look remarkably different. By summer 1998, it was a completely different game.

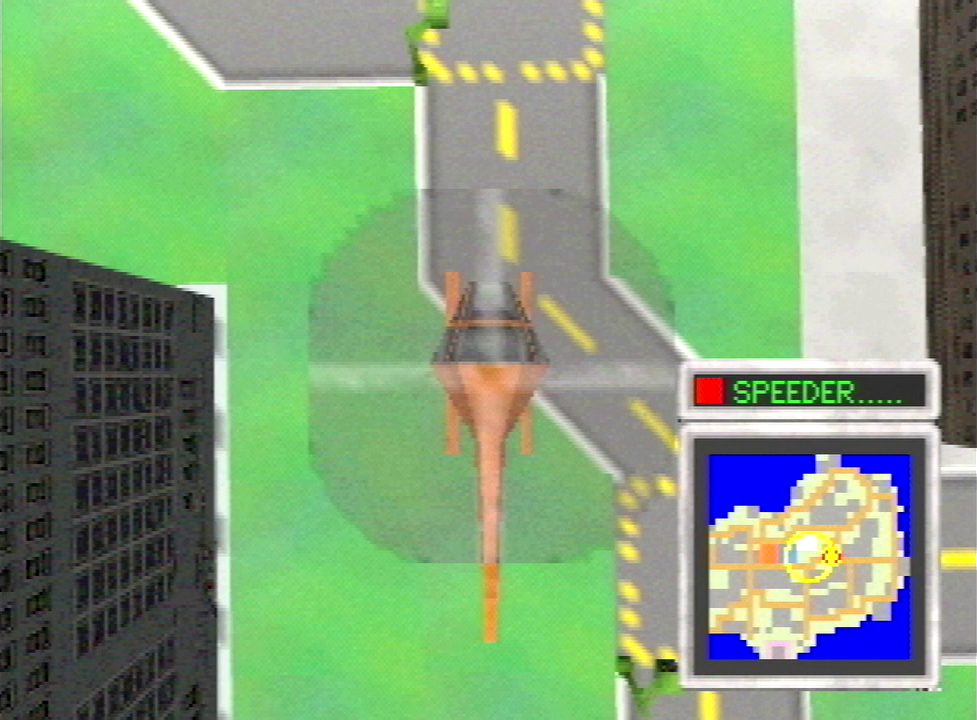

The changes started incrementally. As we can see in footage shared earlier this year from a build of SimCopter 64 dated December 26, 1997, the game got a makeover that was even brighter, cutesier, and more colorful than before.

According to design documents provided to the Video Game History Foundation by Jeffrey J. Feil, SimCopter 64 was starting to take a more overtly game-like approach at this point. Instead of the open-ended sandbox gameplay of the PC version, SimCopter 64 now had levels and missions! The thirty default cities from the original SimCopter were gone, and in their place, the game would send players to four new regions with increasing levels of difficulty: California, Japan, Egypt, and the Alps.

Sometimes, the missions would be simple, like the traffic jam seen in the video. Others would be complex, region-specific challenges, like a mission in California where the player deals with the aftermath of an earthquake. Players would be awarded points for beating missions as quickly as possible — and also by collecting “point tokens,” which show up in the video as well. (They also appear on the HUD in the Space World screenshots, meaning that the change in the direction was underway by then.)

While this sounds pretty different from the original SimCopter, it’s not as different as you might expect! The original SimCopter has a Career mode where you earn points by completing missions across a series of increasingly difficult levels. This version of SimCopter 64 sounds like a plussed-up version of Career mode, rejiggered to better fit the sensibilities of the Nintendo 64.

The most dramatic changes, however, were still to come.

By mid-1998, the entire premise of the game had changed. Based on these design documents — and confirmed by Japanese press coverage — SimCopter 64 was now a story-driven action game where players had to stop the dastardly international criminal organization known as the Heko Heko (ヘコへこ団) from taking over the world.

The scope of this new version of SimCopter 64 was smaller, but tighter. While random emergencies would still pop up during gameplay, the focus had shifted to a smaller number of story missions in each region with multiple tasks for the player to complete. In one example outlined in a design document dated May 5, 1998, if a mission involved the Heko Heko starting a fire, the player would need to put out the fire, capture the Heko Heko arsonists, and airlift any injured Sims to the hospital.

These are still functionally the same activities players do in SimCopter, but the story-based level-and-mission structure is a radical departure from the freeform toy playset vibe of the original game. It was still being pitched as a “nonviolent action strategy game,” but it was also edging closer to the wacky, cartoon shenanigans you might expect from a Japanese Nintendo 64 game. In place of the guns and missiles used to stop criminals in the original SimCopter, the player’s chopper in SimCopter 64 was equipped with a giant net for catching the Heko Heko and an honest-to-god laser beam weapon, which Feil pushed back against for being a step too far.

As SimCopter 64 went on, the wacky shenanigans (and the difficulty) would escalate. Later missions would involve escorting the mayor in order to prevent him from being kidnapped, or a scenario where the Heko Heko use toxic gas to brainwash a bunch of zoo animals to become evil and they break loose and start terrorizing people (we’re serious, that one is actually in the design document).

The game would have culminated in a race against time to stop the Heko Heko from launching “a giant missile” that would wipe out the entire city, a far cry from dealing with traffic jams!

The game described in these documents sounds more like Pilotwings 64 or Blast Corps — two other vehicular action games for the Nintendo 64 — than it does the original SimCopter. Feil, who joined the project in late 1997 or early 1998 when it was already entering this state, remembers it feeling more like a side-scrolling action game in spirit than a flight simulator. “It was much different than I expected,” he says.

The surviving screenshots and video of these later versions of SimCopter 64 (particularly the December 26, 1997 build) show that they were still using the same base as the E3 1997 demo. It still had the same low rendering distance and copious amounts of fog, which continued to be a thorn in the game’s side. It just had so many new features now that it may as well have been an entirely new game. Talk about a big change!

However, the biggest change planned for SimCopter 64 was something that Maxis originally said wasn’t going to happen.

Better together…?

The defining feature of SimCopter has always been the ability to import cities from SimCity 2000, so when Maxis first announced SimCopter 64 in May 1997, they clarified that the Nintendo 64 version would not support this feature, probably because it would have been technically unfeasible on the console. However, just a few months after the E3 demo, Nintendo announced that the game would, in fact, be cross-compatible with the upcoming SimCity 64 by the Nintendo-affiliated studio HAL Laboratory.

So how were they planning to pull it off? They would need to take advantage of a new piece of hardware.

Following months of rumors — instigated by comments that Nintendo’s chief producer and designer Shigeru Miyamoto made to the press — Nintendo officially announced at Space World 1997 that SimCopter 64 would be compatible with the Nintendo 64DD, an upcoming disk drive add-on for the console. The 64DD was meant to be Nintendo’s answer to the CD-ROM storage format used on their competitors’ consoles, in particular the Sony PlayStation. Rather than competing with the CD-ROM on storage size, the re-writeable add-on 64DD disks were designed to support new game concepts, like games that could interact with each other. The sci-fi racing game F-Zero X, for instance, could connect with the F-Zero X Expansion Kit for the 64DD to enable new features like a track editor.

Now SimCopter 64 was going that way too. The idea, explained Nintendo software engineering project manager Jim Merrick to Electronic Gaming Monthly, was that even though SimCopter might only be released as a cartridge-based game, the Nintendo 64DD hardware would allow the game to import save data from SimCity 64, which had been announced as one of the 64DD’s launch titles. Miyamoto doubled down on this idea in Nintendo Power, telling the magazine that SimCopter 64 players would be able to put out fires in the cities they built in SimCity 64.

This was a big commitment for all parties involved. Being able to port entire cities from one game to another was certainly one of the most tantalizing features in the Nintendo 64DD game lineup. Nintendo and Maxis initially hedged their bets about what format the game would be released for, but as hype grew around the mysterious 64DD, the American and European gaming press came to believe that SimCopter 64 would be a full-blown 64DD title. What started out as a bonus feature was now expected to be the game’s main attraction.

But knowing what we do about the mission-heavy, geographically locked vision for SimCopter 64, it’s difficult to imagine how these games would have worked together.

Maybe that’s because they never did.

Based on our interviews with former Maxis staff and our review of the game’s design documents, we believe SimCopter 64 was never compatible with any other game, and in fact, it was never in development for the Nintendo 64DD at all!

During his time on the project through mid-1998, Feil never received a build that interacted with the Nintendo 64DD or heard anything about connectivity with SimCity 64. The last major press coverage of SimCopter 64 was an article from the August 1998 issue of the Japanese Nintendo magazine The 64Dream, and even though development had progressed far enough by that point that the game had a release date, there’s absolutely no mention of the 64DD in the article.

Kodama confirms to the Video Game History Foundation that Maxis K.K. had been working with Nintendo and Satoru Iwata’s team at HAL Laboratory on SimCopter 64, and although they had explored the idea of crossing their games over, he says the feature was never implemented, and that he had “never seen” a 64DD build of the game. The frequent delays and eventual commercial failure of the Nintendo 64DD hardware guaranteed that the idea was dead in the water.

If a 64DD version of SimCopter 64 ever existed, it would probably have been a test build of the game running off a disk instead of a cartridge, not anything that took advantage of the unique features of the hardware. Despite Nintendo’s lofty announcements about the 64DD, SimCopter 64 was never anything but a standalone Nintendo 64 game.

Out of fuel

Maxis wanted SimCopter 64 to be the start of their new development empire, but when they got acquired, those plans were cut short. Nintendo wanted it to be a headliner for their new hardware, an idea that quickly fizzled out. Whatever people wanted SimCopter 64 to be, it wasn’t.

Without a strong mandate to exist, SimCopter 64 struggled to find its footing. The game’s design seems to have been up in the air even in the middle of production. Design documents say SimCopter 64 was going to be a linear game with a ticking timer for each mission, but Japanese press coverage a few months later suggests it was going to be open-ended and leisurely paced. It’s hard to say what the final state of the game was.

As development wore on, SimCopter 64 became less and less of a priority. The higher-ups at Electronic Arts had been refocusing Maxis on a smaller number of core titles, and the meandering SimCopter 64 was not one of them. According to Buechner, EA’s top concern at that time was finishing SimCity 3000, which Maxis had basically restarted after its poor showing at E3 1997. Side projects like SimCopter 64 “may have been seen as distractions,” he says.

Feil and Davis were transferred off the game in mid-1998; Feil went to help with the upcoming SimSafari and later SimCity 3000, while Davis moved over to Moto Racer 2. If Electronic Arts was triaging both producers of SimCopter 64 to work on other products, they certainly weren’t putting other people on the project in their place. We’re not sure who if anyone in the United States was still working on the game after that point, or if Electronic Arts effectively abandoned it.

Maxis had originally scheduled SimCopter 64 for release by the end of 1998, which grew increasingly unlikely as time went on without updates. Nintendo’s licensee index for E3 1998 indicates that SimCopter 64 skipped the show that year, and as far as we can tell, it never appeared at an event again. The 64Dream reported that the game would be released on September 25, but to their disappointment, September came and went with nothing.

A few magazines still anticipated the game might reach shelves by the end of the year, but as news dried up, it disappeared from their release schedules. While SimCity 64 did eventually come out in Japan in 2000, SimCopter 64 was out of the picture.

By March 1999, IGN reported that the game had been quietly canceled, claiming that Maxis had lost faith in the project. One of the issues, the report explained, was the game’s dated, fog-drenched graphics, which had been a problem since E3 1997 and were poorly received when the game appeared at Tokyo Game Show the previous spring.

IGN also claimed that the game had already been canceled for the United States by this point and that Maxis had been reworking it as a Japan-exclusive title for the Nintendo 64DD, but as we know, there was probably never a meaningful 64DD version to begin with. With the add-on hardware’s failure apparently dashing any last-ditch attempt to salvage the project, it was finally canned. Kodama left Maxis K.K. around the same time, which also probably marked the end of original development at the studio.

The game just never came together. Kodama says that despite the new scenarios and the tighter focus, it simply wasn’t working. “We found the nature of SimCopter was not a good fit for [a console] video game,” he says.

Everyone had their own idea about what SimCopter 64 should be. What it actually ended up being was a rudderless game that nobody believed in, and it was quietly shelved. It’s not a story with a dramatic ending, just a project that didn’t work out.

The E3 1997 build obtained by the Video Game History Foundation adds a new wrinkle to this story — an early version of the game, far different from the other screenshots floating around the internet, back from when Maxis imagined it as a more straightforward translation of one of their computer games into the console space. When they changed course, it set the stage for the rocky development of one of the Nintendo 64’s most intriguing what-ifs.

With so many different iterations of the game across two years of development, it’s hard to get a handle on what exactly SimCopter 64 was. If other builds of this game surface in the future, we can get a better look at where it was heading!

Acknowledgements

We hope this was a fun example of the video game history research you can do with primary sources: development builds of games, press sources, and developer interviews all fitting together to tell a video game’s story.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider donating to our non-profit organization. The Video Game History Foundation’s goal is to make more research like this possible!

Like all video game history research, this article would not have been possible without the work done by the community. Thanks to Unseen64 for gathering many of the previously known sources about SimCopter 64; the Strong Museum of Play for cataloging Maxis’ E3 1997 press kit; Dale Floer for documenting the SimCity 2000 save file format; queueRAM for developing Texture64; Aleksander Krimsky for developing the SimCopterX program used to capture screenshots of the original SimCopter; Retroactive for designing the hardware used to dump this development cartridge; and Kevin Bunch for helping capture the screenshots and videos in this article using his hardware.

Thanks to Patrick Buechner, Brian Conrad, Dave Davis, Jeffrey J. Feil, and Aki Kodama for their contributions to this story, with special thanks to Feil for donating copies of his development materials to the Video Game History Foundation!

If you have any other information about SimCopter 64, please contact us at info@gamehistory.org!

Additional Sources

“64DD: The Games.” January 29, 1998, IGN.com.

Interview with Shigesato Itoi and Shigeru Miyamoto, The 64Dream, December 1997 (vol. 15), MYCOMムック. Translated by Lindsay (Chewy), via Yomuka!

The 64Dream, February 1998 (vol. 17), MYCOMムック, p.136.

The 64Dream, August 1998 (vol. 23), MYCOMムック, p.53.

The 64Dream, October 1998 (vol. 25), MYCOMムック, p.140.

Aki Kodama [LinkedIn page], n.d. Retrieved on September 2, 2022.

E3 1997 show floor map, n.d. Uploaded to Giant Bomb by Brad Lynch (marino).

“E3 1997 The next Generation VHS Messevideo (Trade Show Video).” Uploaded to YouTube by Old E3 VHS Videos.

“E3: EA: Inside The Maxis / EA Deal.” June 21, 1997, IGN.com.

EGM’s Player’s Guide To Video Games For The Nintendo 64, June 1998, p.96.

Electronic Arts, Inc., Form 10-K, EX-21.01, Subsidiaries of the Registrant, filed May 22, 2009, via SEC.gov.

Electronic Gaming Monthly, February 1998 (vol. 11, no. 2, issue 103), Ziff-Davis Inc., p.20.

“Four Games to Launch with Japanese 64DD.” June 2, 1997, IGN.com.

Maxis, 10 Years of Fun and Games [E3 1997 press kit], June 1997, from the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at the Strong Museum of Play.

“Maxis Enters Picture with SimCopter.” May 22, 1997, IGN.com.

Maxis Inc., Form 10-K, filed, June 20, 1996, via SEC.gov.

Maxis Inc., Form 10-K, filed June 24, 1997, via SEC.gov

monokoma, “SimCopter 64 [N64DD – Cancelled],” Unseen64, June 23, 2010.

N64 Pro, April 1998 (no. 6), IDG Media, p. 58.

N64 Pro, October 1998 (no. 12), IDG Media, p.15.

Nintendo Acción, año. 7, no. 62, Hobby Press, p.16.

Nintendo of America, 1998 Licensee Index, May 1998 [E3 1998], from the Video Game History Foundation Research Library.

Nintendo Power, January 1998 (vol. 104), Nintendo of America, p.38.

“SimCopter to Fly to US.” February 9, 1998, IGN.com.

“Sim Copter Crashes.” March 9, 1998, IGN.com.

“Sim Copter Shuttles to 64DD.” October 9, 1997, IGN.com.

SimCopter Japanese release information, 1996, via Media Art Database.

SimTunes packaging, Japanese release, 1996.

Total 64, March 1998 (vol. 2, no. 2, issue 14), Rapide Publishing, p.7.

Ultra Game Players, April 1998 (issue 109), Imagine Media, p.25.

Notes

- ^ Neither magazine identified the source of these screenshots, but coverage of SimCopter 64 in the Spanish magazine Nintendo Acción says that these pictures came from Space World 1997.

- ^ Although the August 1998 issue of The 64Dream was the magazine’s E3 special, several other games in this issue are known to have been featured at Tokyo Game Show that spring, which would be a more likely venue for Japanese-language games. We assume that’s where this build of SimCopter 64 was shown.

- ^ We tried to run as much legible text in these screenshots through Google Translate as possible, but the Heko Heko’s dialogue proved more cryptic. The first line (これから悪さをするヒ~) is simple enough and roughly translates to “From now on, I’m gonna do bad things!” The second line (スカッドのノロマ~, romanized as “sukaddo no noroma”) is less clear. According to the design documents for SimCopter 64, SCAAD was the name of the player’s anti-crime organization, so the Heko Heko henchman seems to be mocking SCAAD (“sukaddo”) by adding “of dimwits” (“no noroma”) to their name while they’re getting away on a train car. Maybe you could localize this in English as something like, “See ya, SCAADummies!”