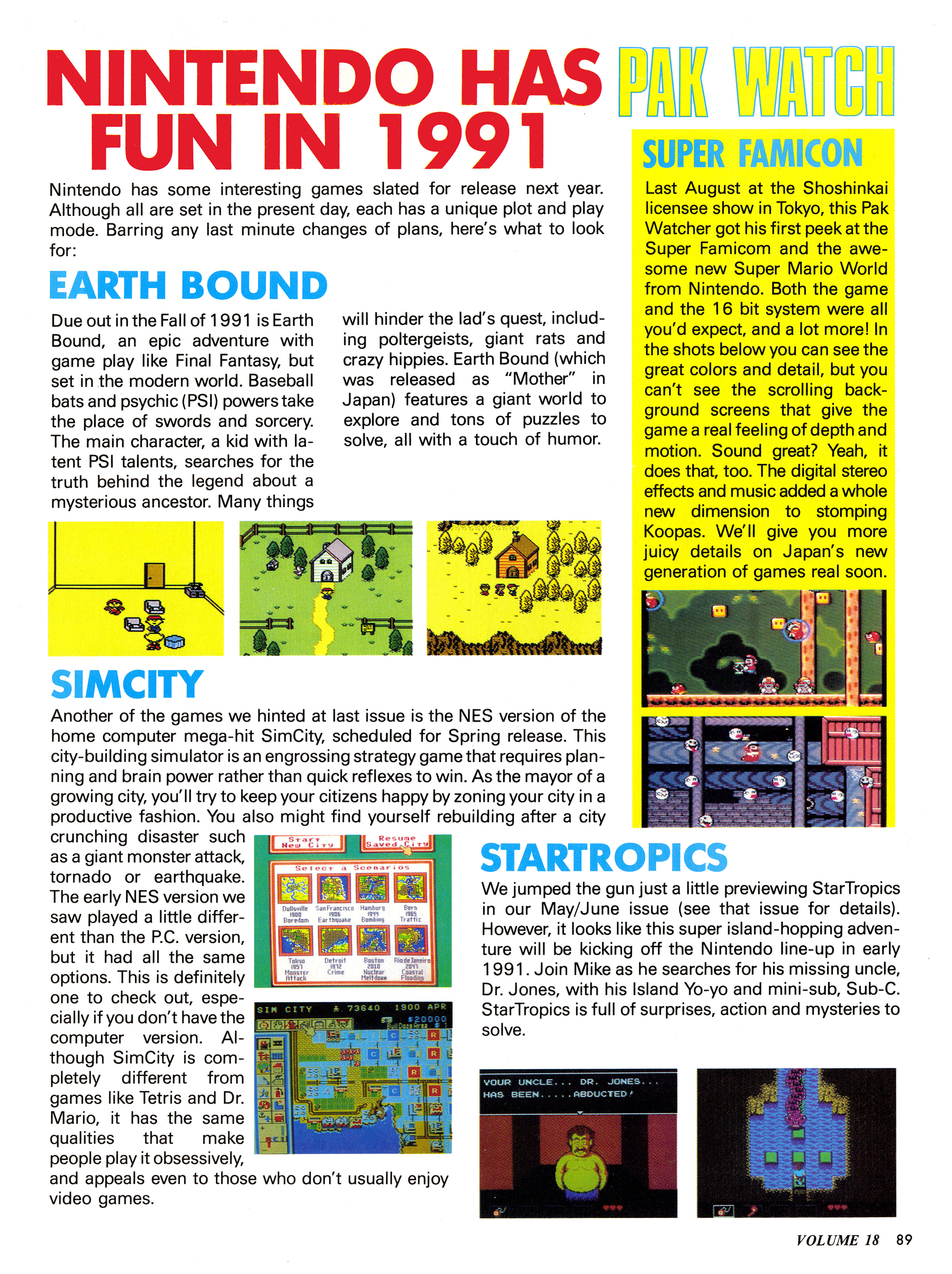

A lot of you are probably aware of Nintendo’s remarkable rendition of SimCity for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. The cartridge launched alongside the system here in the United States, and brought the popular PC game to a brand new console audience. But did you know that Nintendo’s version of SimCity actually started life on the original 8-bit Nintendo Entertainment System?

This version of the game was announced at the same time as its 16-bit cousin, and was said to contain all of its same features. It made a brief appearance at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in 1991, but was canceled soon after, and was never seen again.

This version of the game was thought to be completely lost or, at best, confined to some deep dark archive inside of Nintendo’s offices. Either way, the game was seen as something of a Holy Grail among collectors and archivists alike, and the odds of ever seeing it outside of a handful of published screenshots seemed slim, until a cartridge containing an unfinished version of the game materialized at 2017’s Portland Retro Gaming Expo.

We had the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to digitize the game for its owner at the show, and thanks to two very generous collectors, we were able to spend the last few months tearing the game apart for the following deep-dive analysis. Seen here for the first time in nearly twenty-seven years, this is SimCity for the Nintendo Entertainment System.

At a glance, the game doesn’t look like much more than an inferior version of the SimCity we saw on the Super Nintendo. However, once put into context, this artifact becomes extraordinary, and gives us new insight into one of the most unlikely creative collaborations in video game history. And to understand just why that is, we’re going to have to give you a brief history lesson first.

The Birth of SimCity

The original version of SimCity was written by Will Wright for the Commodore 64 as a follow-up to his first game, 1984’s Raid on Bungeling Bay, a helicopter flight simulator that was published by Brøderbund.

As Wright often tells it, the germ of an idea for SimCity actually evolved out of Bungeling Bay’s map editing tool.

“I found out that I had a lot more fun building the islands than I did flying around in the helicopter,” Wright told GameSpot in a 1999 interview.

Wright combined this city-building tool with his love of system dynamics, and began tinkering with what was essentially a toy to simulate the effects of economics and population growth on a virtual city: not necessarily as a game mechanic — at least, not yet — but more as a virtual sandbox.

Ironically, it was the success of Nintendo’s 8-bit console that allowed Wright the financial freedom to spend time tinkering with this experiment. In 1984 in Japan, software creator Hudson Soft was among the first third-party publishers to get in on the ground floor of selling games for Nintendo’s new hit console, the Family Computer – or as we know it, the NES. Among its first products was a conversion of Wright’s Raid on Bungeling Bay, the rights for which the company licensed from Brøderbund.

Here in the U.S., the game had sold about 30,000 units for home computers, a number no doubt hampered by the Commodore 64’s rampant piracy. In Japan, where the Famicom’s early adopters were hungry for new games – and where piracy of its cartridge-based games was in its infancy – the game sold about 750,000.

“Back then the terms you got from the publishers was pretty generous, because they didn’t spend much on marketing or anything like that,” Wright said in an interview with Tristan Donovan for his history book Replay. “I earned enough off of that game to live for several years, and that’s when I was working on SimCity.”

“After about six months or so I started attaching some graphics to it. It was fairly abstract to begin with,” Wright told author Richard Rouse III. “And then I started thinking, you know, this might be an interesting game.”

Wright showed a prototype to friends at Brøderbund, who agreed to license the title from him as a commercial game. Wright continued to work on it for about a year, polishing it until he felt it was done, but Brøderbund was reluctant to publish.

“They kept saying, ‘When is it going to be a game? When is it going to have a win/lose situation?'” Wright told Rouse.

Ultimately Brøderbund decided not to market the game, and it remained dormant for years, until Wright showed it to Jeff Braun, who saw its commercial potential. Instead of finding another partner, the two co-founded their own software company, Maxis, and converted the game to the newer Amiga and Macintosh platforms, while also adding some new features.

This simulation-based concept was practically a new genre for home computers, so the game was a slow burn after its February, 1989 release. But sales quickly ignited as word-of-mouth and press accolades spread. By 1992, the game would sell a million copies.

The Nintendo Connection

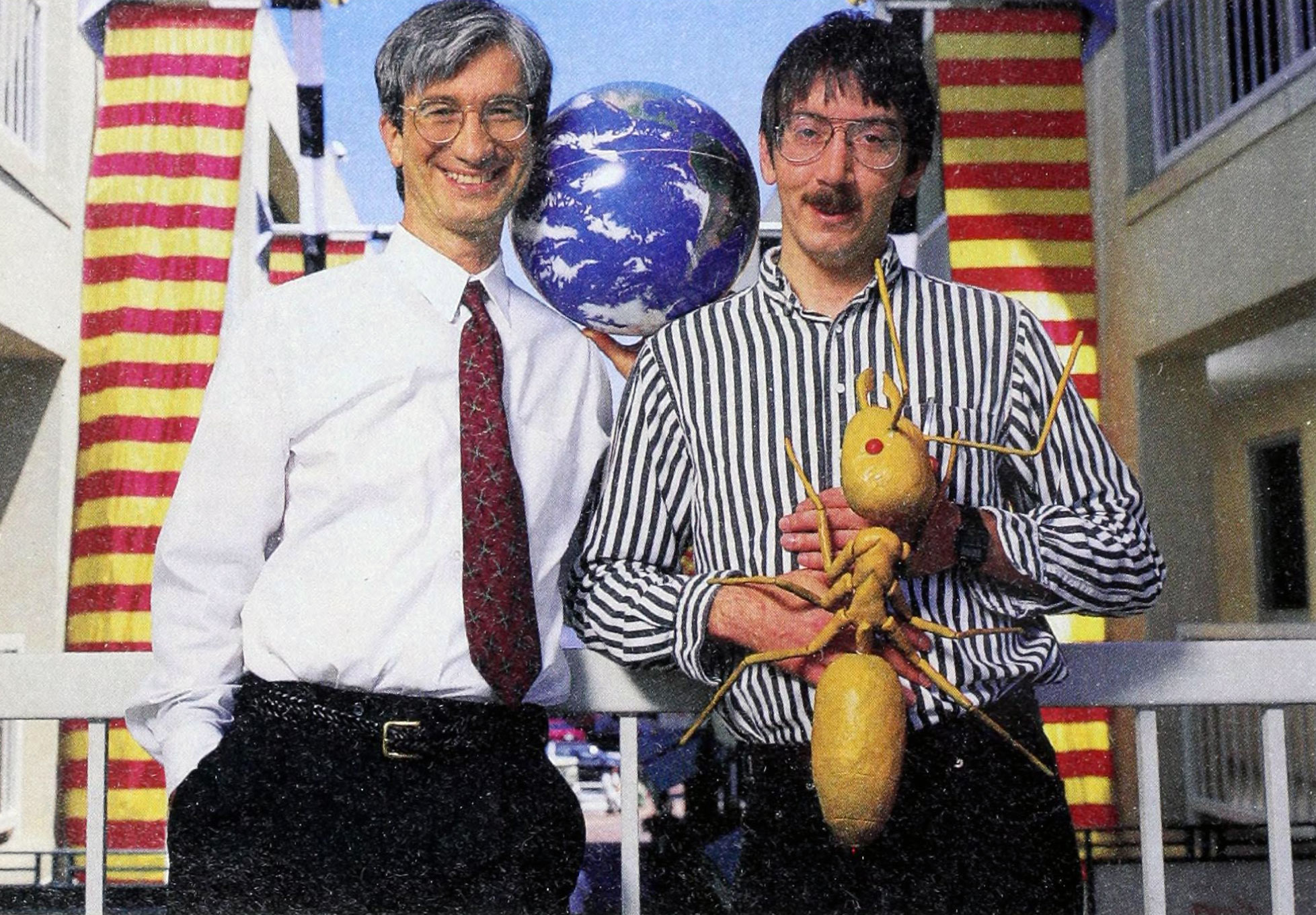

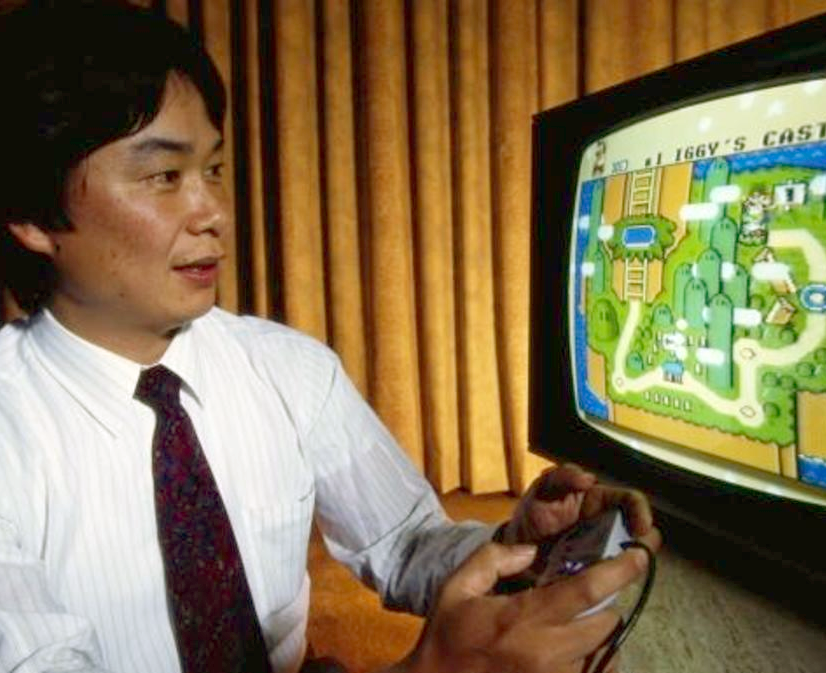

Meanwhile in Japan, Nintendo was planning software for its upcoming console successor, the Super Famicom. The company’s star designer, Mario and Zelda creator Shigeru Miyamoto, was tinkering with the idea of a city-building game, unaware that a game similar to what he had in mind already existed in SimCity.

“When we were first developing game ideas for the Super Famicom, I proposed a game that allowed you to create your own world,” Miyamoto told Nintendo Power magazine for a feature published in its February, 1991 issue. “I was pleasantly surprised to find that a great game like the one I envisioned already existed in SimCity.”

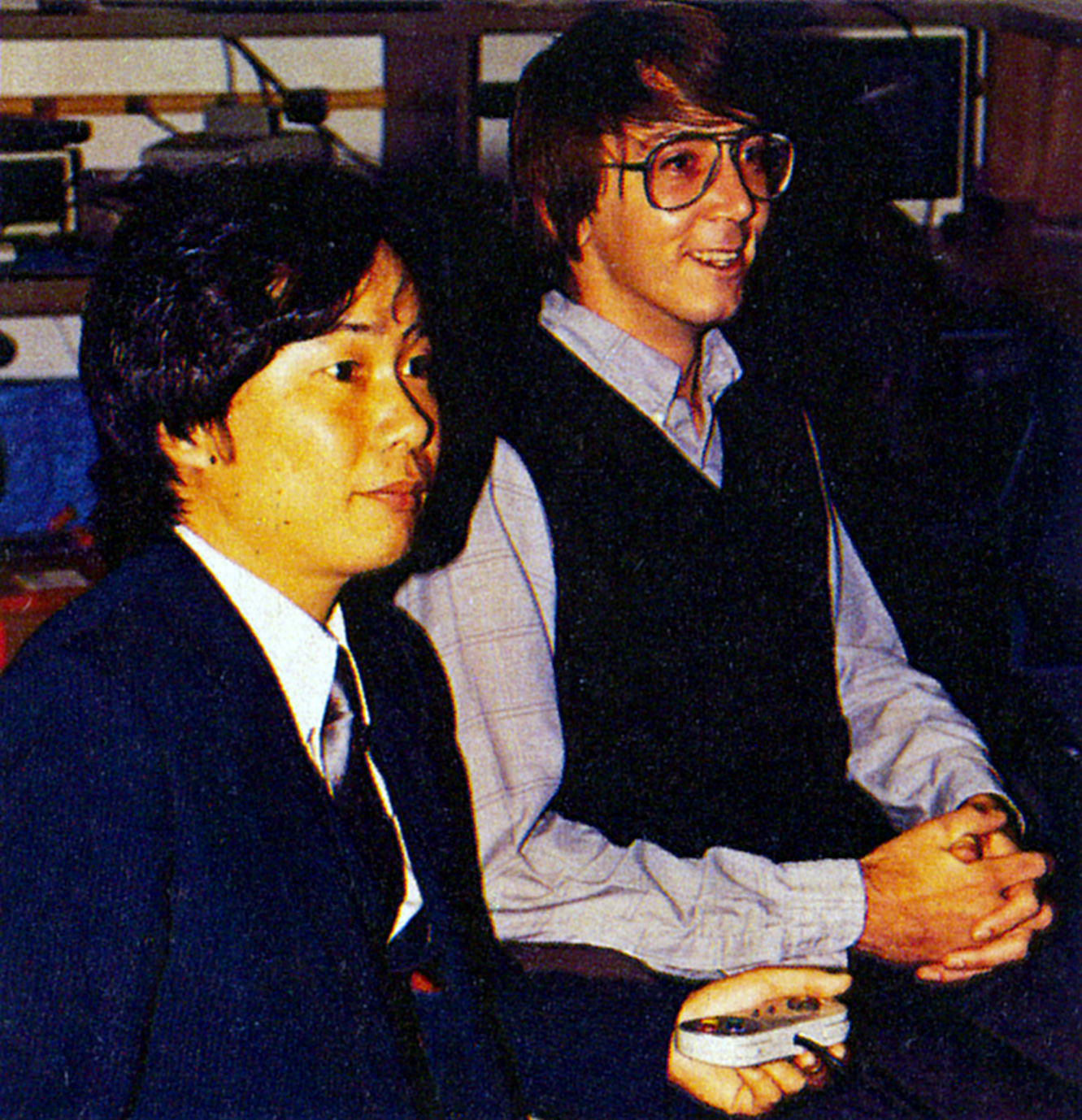

Negotiations began between Maxis and Nintendo to obtain the console rights to SimCity. A group of Nintendo employees, including Miyamoto, flew out to Maxis in Emeryville, California, and spent some time seeing the sights and getting to know the team. Eventually a deal was struck, with Nintendo paying an undisclosed amount of money. We still don’t know exactly how much, but one rumor from the time put the price tag north of $1 million.

Here’s where things get really interesting. After the deal was signed, Will Wright was flown to Nintendo’s headquarters in Kyoto, where he and Miyamoto spent a week redesigning the game, moving it further away from its hardcore simulation roots and toward a Nintendo-friendly console game.

Think about this. In 1990, two famous game designers from opposite ends of the globe sat down and collaborated. The guy who just shipped SimCity, probably the most famous computer game at the time, and the guy who just shipped Super Mario Bros. 3, probably the most famous console game of the time, came together briefly to combine forces on a project.

The unlikely combination of Miyamoto’s mastery of joyous movement and Wright’s fascination with computational systems merged beautifully into an experience that neither Maxis nor Nintendo could have accomplished on their own. SimCity, a mouse-driven game that seemed like it could only ever work on a computer, somehow evolved into a game that felt like it had always belonged on consoles, without losing anything in the process. It was a design miracle.

What makes the NES SimCity find really remarkable from an historical perspective is that it was developed before the Super Nintendo version, which means that not only do we have the final product to come from this collaboration, we now also have a rough draft. The NES prototype gives us insight into some of those collaborative ideas that didn’t make the final cut! We’ll get into those later, but first we need a primer on the new ideas that came from the Wright-Miyamoto collaboration.

Turning SimCity Into a Nintendo Game

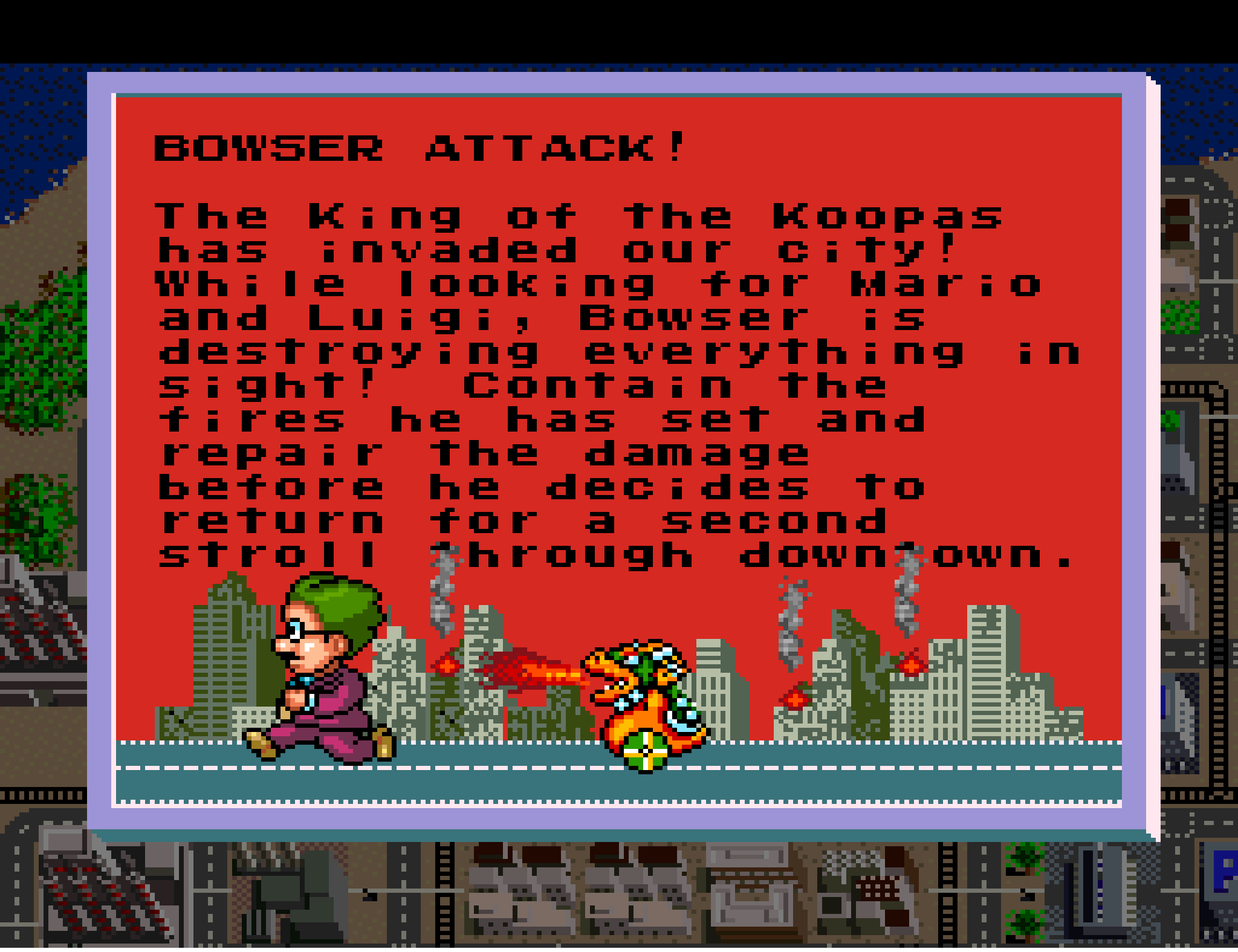

https://www.youtube.com/embed/qwOk88bvDx4 Nintendo created a brand new character, Dr. Wright, to help add personality – as well as a friendly tutorial – to the game.

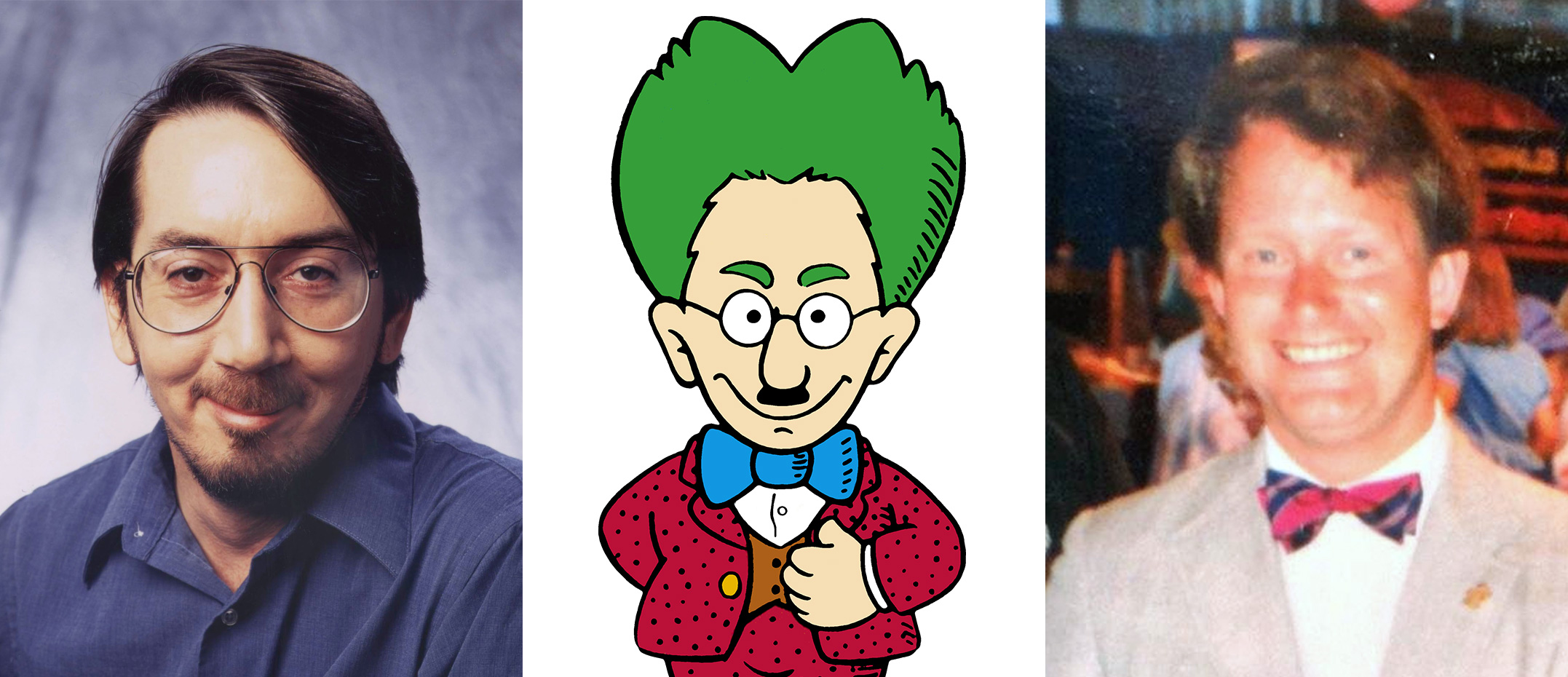

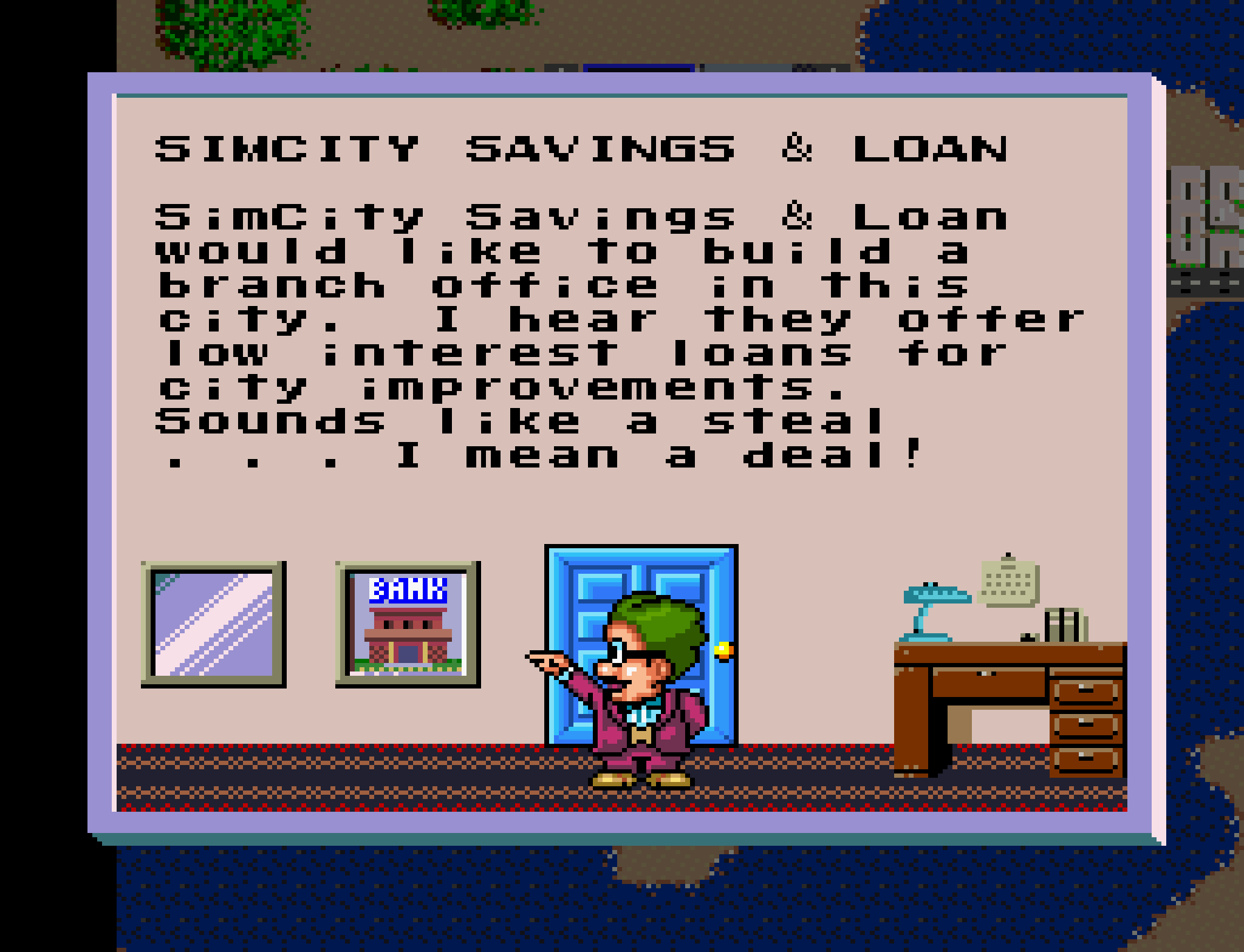

The most memorable addition to Nintendo’s new version of SimCity was a cartoon virtual adviser, Dr. Wright (named, obviously, after Will Wright). While the original SimCity tossed players right into the simulation, expecting that they’d read the included documentation, Dr. Wright eased players into the experience by slowly explaining what might otherwise be complex mechanics. He also brought a fresh personality to the game, showing excitement when the player did well, comically tripping over himself, and even getting annoyed should the player bother him too much for advice.

A quick sidenote: did you know that the Japanese and American designs for Dr. Wright are different? In the U.S., his colors were toned down, and his bow tie changed to a more formal necktie. Perhaps this was just more relateable to Americans…or maybe Nintendo of America figured it only had room for one bow tie-wearing mascot – Game Counselor head and “Fun Club President” Howard Phillips.

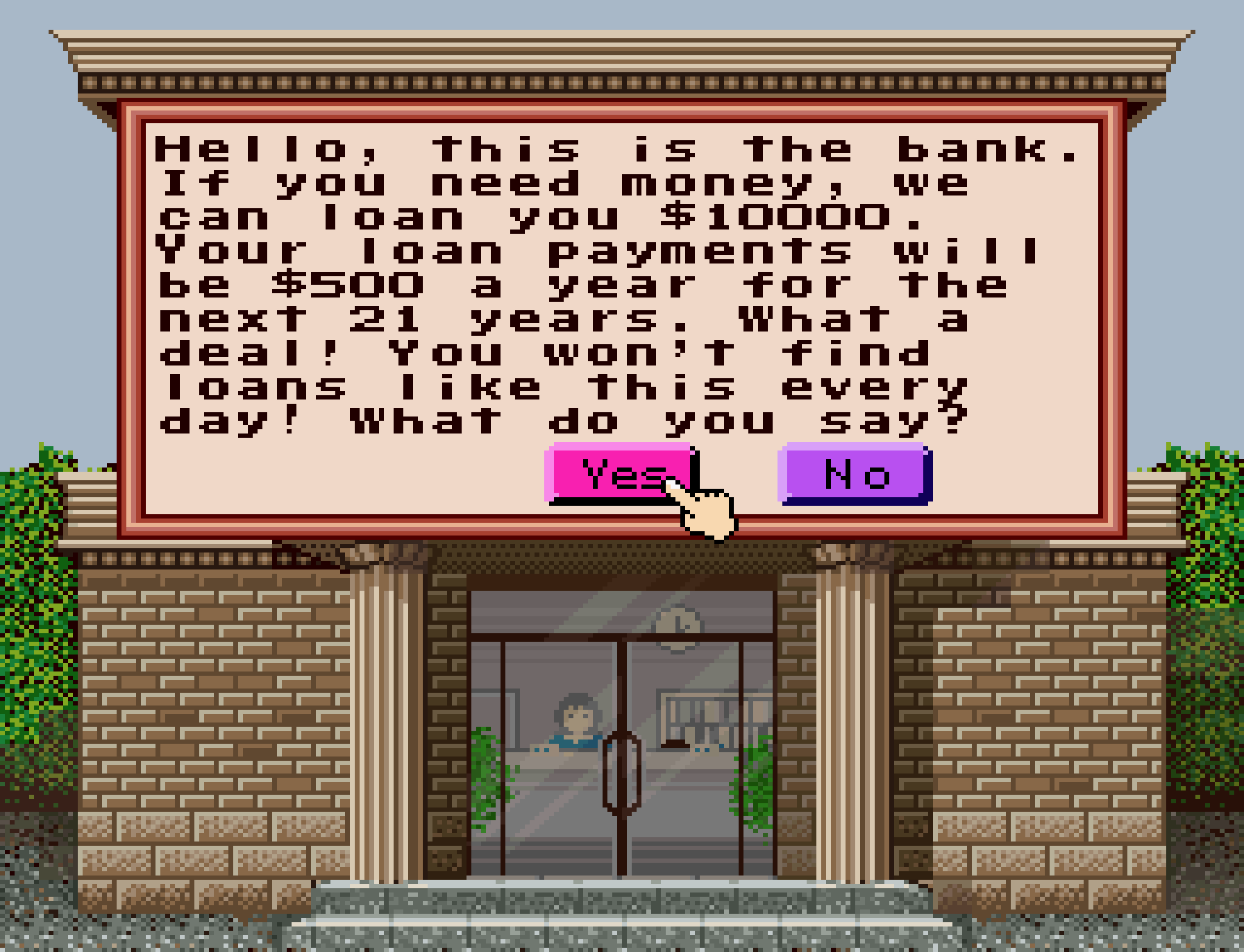

Another much-needed addition was the bank loan. The original SimCity demanded the player spend their available funds very, very conservatively, because you can’t do anything in SimCity without money. You can’t grow your city, you can’t fix roads, and you certainly can’t respond to natural disasters. When a player ran out of money, it became a waiting game, with additional taxpayer money coming in only at the end of every virtual year.

While this is still true in Nintendo’s version, the bank alleviates this quite a bit, allowing players to take out a massive lump sum to be paid back in slow, small increments. The bank is also time-based, and appears right around when most players are running out of money. While additional funding was available in other versions of the game via what amounted to a cheat code, making this a part of the official game design was a much-welcomed acknowledgment that it actually made the game more fun.

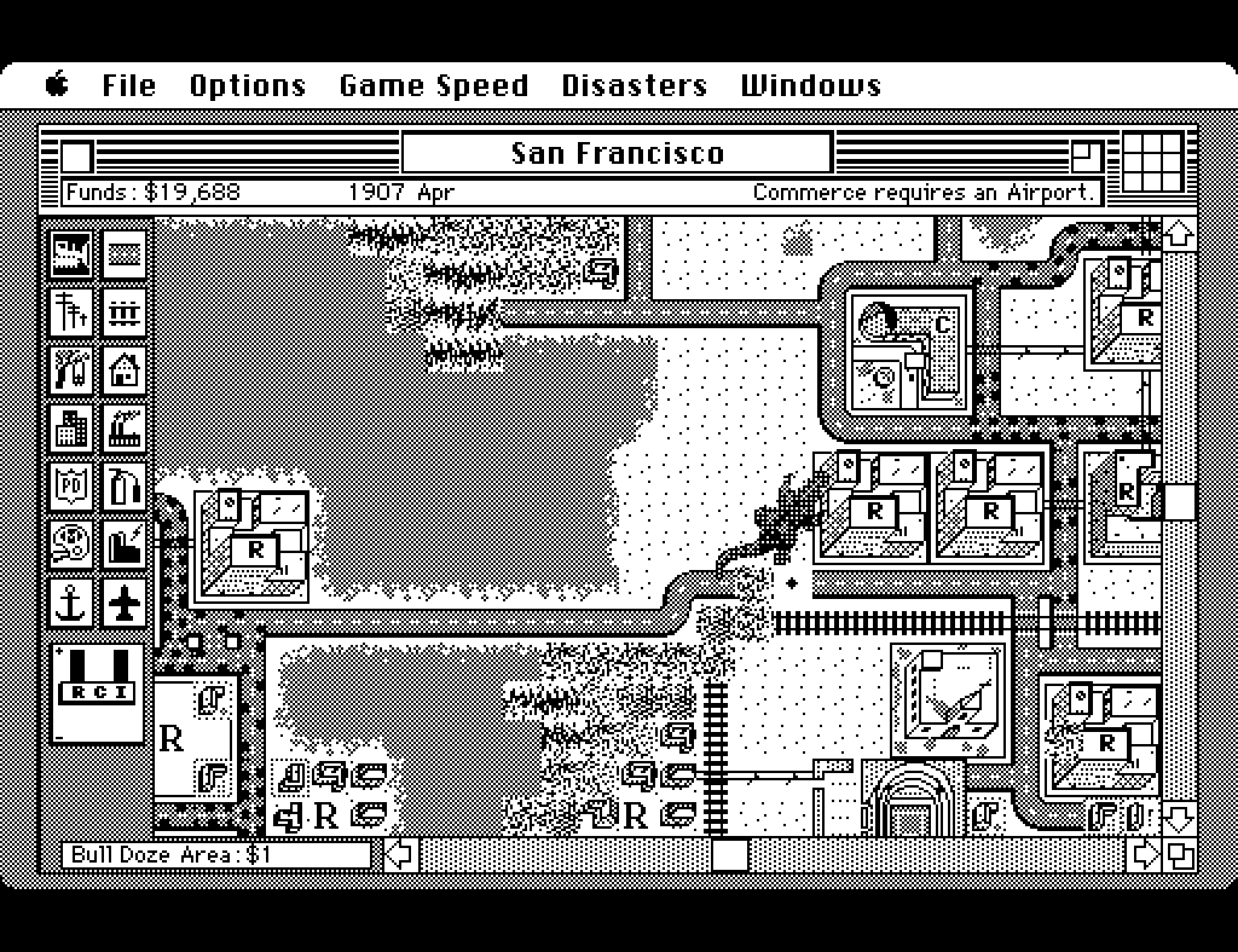

Most importantly of all, Nintendo’s version of SimCity finally managed to turn the simulation into a proper game. Wright’s original version for the Commodore 64 wasn’t meant to be a game, it was more of a simulation toybox. While its optional Scenario mode attempted to add traditional game mechanics, it comes across as a reluctant add-on, probably in response to Broderbund’s reluctance to sell the title. In fact, in the original Commodore 64 version, the scenarios had no win or lose parameters at all – at least, not in the software itself. Want to see if you can help San Francisco recover from an earthquake? If you’re the player, it’s all on you. The instructions tell you to load the pre-made San Francisco city layout, manually trigger an earthquake, and get to work. Whether you win or lose is entirely based on the honor system.

Maxis’ updated versions for the Amiga, Macintosh and later IBM PCs improved this feature somewhat. Now, a scenario’s disasters happen automatically, and players are given a time limit to solve the problem.

This is what passed for a game when it came to the computer version of SimCity. And while similar scenarios are available in the Nintendo version, it is a handful of simple but ingenious additions to the main simulation itself that finally brought the video game mechanics to SimCity that Brøderbund felt was missing. Any goals for virtual mayors on computers were entirely for them to decide and enforce. There was no end state, no congratulatory messaging…there wasn’t even a game over. A player could rack up an infinite amount of cash or an infinite amount of debt, the software just didn’t care.

This new design added just what SimCity always needed: a sense of progression. Players of Nintendo’s version would see their humble plots of land graduate as their populations grew, from a town to a city and beyond. Each time a population milestone was met, Dr. Wright would appear to congratulate the player. Afterward, the music itself that plays during the game would change, reflecting a city’s growing complexity.

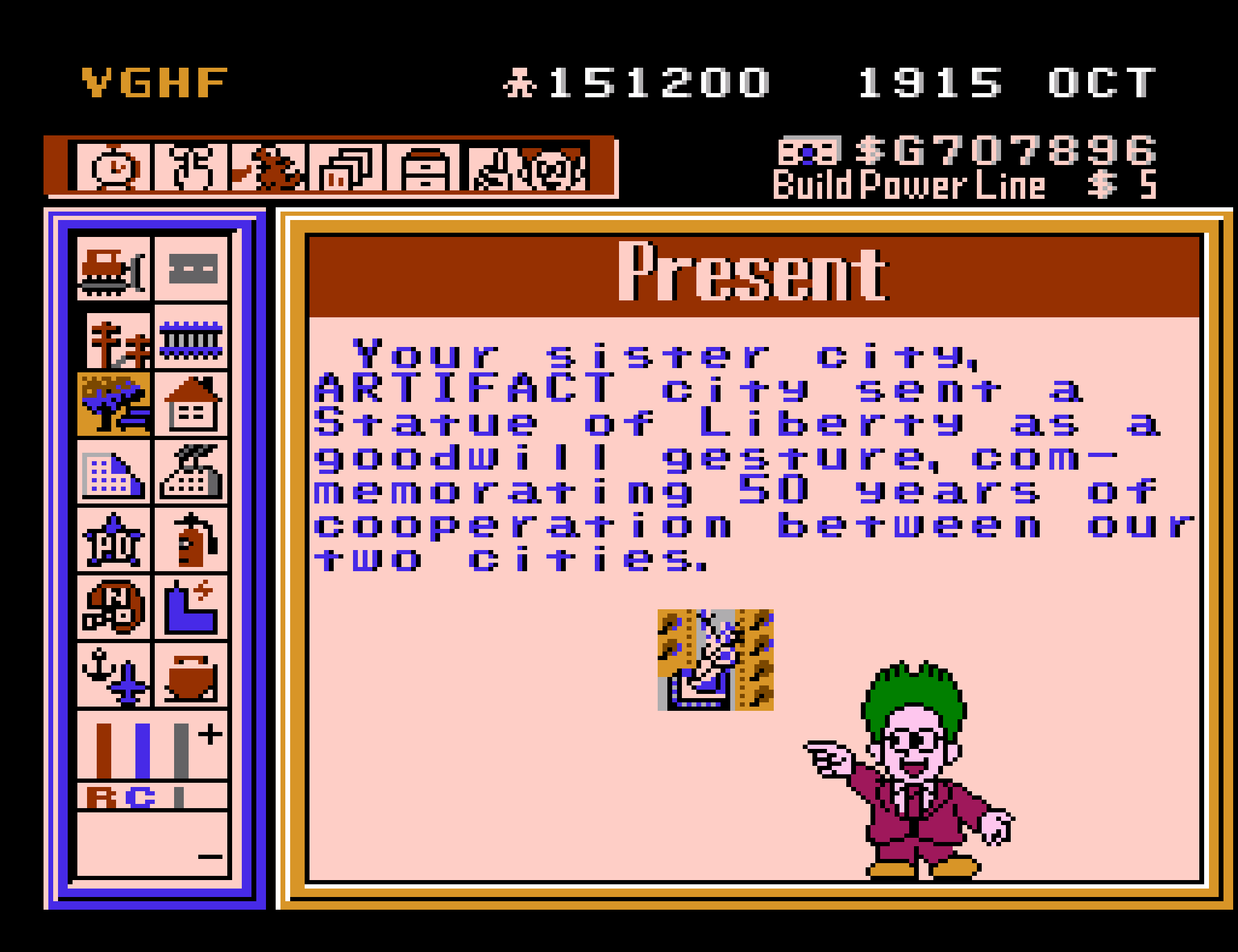

And in what is the most Miyamoto-esque touch of all, players would occasionally get presents as they progressed. The original SimCity never strayed from its default tile set: players could zone areas on the map to be residential, commercial or industrial, but it was up to them to imagine any fun buildings that might be in those zones.

The present system allowed players to add some fun new pieces to the map, such as theme parks, zoos, and train stations. And they weren’t just fun to look at: they also increased the land value of surrounding tiles, adding a new layer of strategy for building a perfect city.

Many of these new ideas were so good that Maxis would go on to use them in its own sequels. This new version of SimCity was undeniably an improvement on the original.

The Announcement

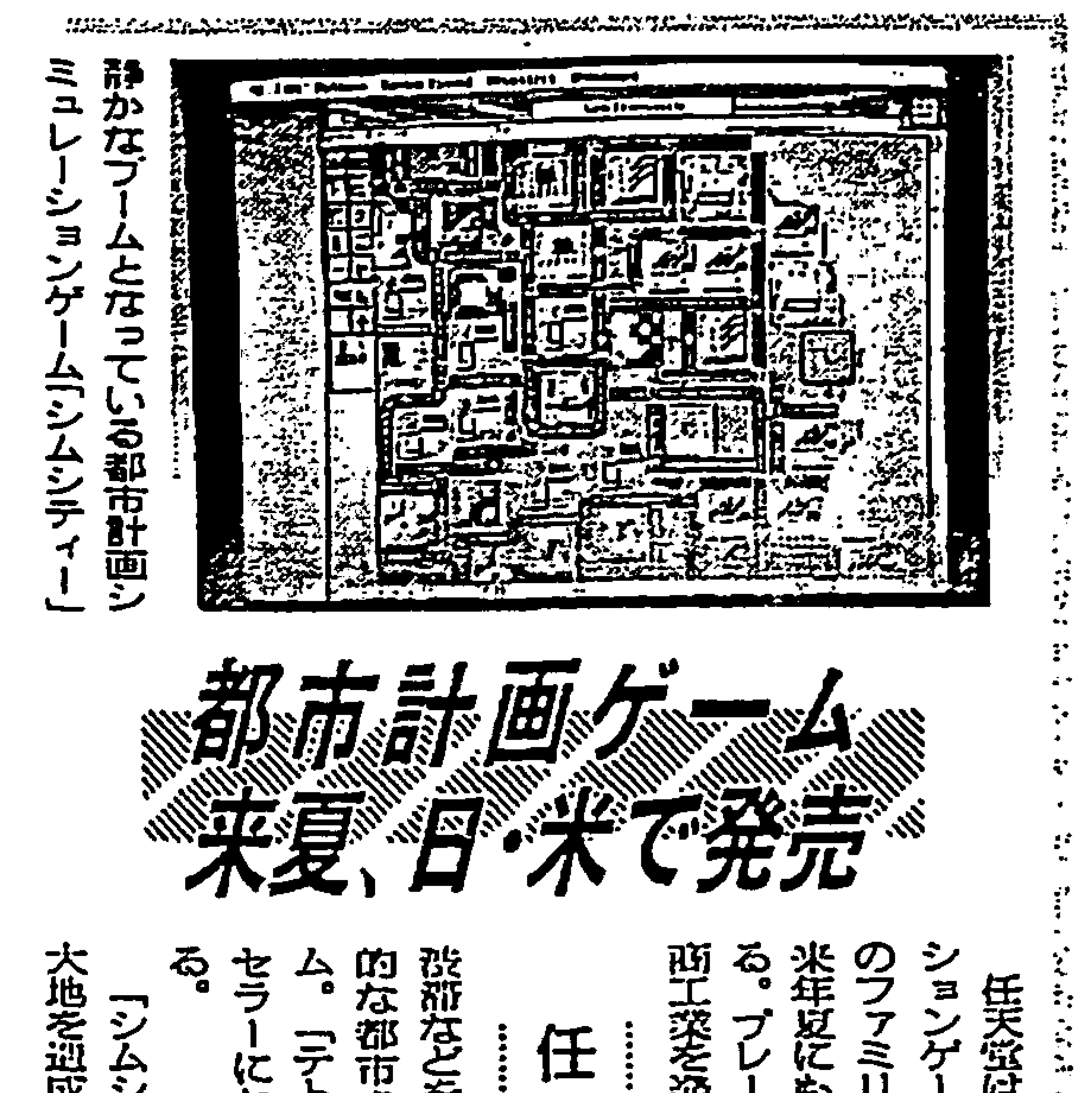

We don’t know exactly when Wright’s week in Kyoto took place, but we do have a paper trail of when Nintendo and Maxis announced their partnership. The earliest report we could find was in the June 7, 1990 edition of The Nikkei (nick-kay). The story says that two versions of the game – a Super Famicom version in Japan and a Nintendo Entertainment System version in the United States – would be out in summer of 1991.

This was true for the Super Famicom, which saw SimCity debut on April 26, 1991. An American release for the Super NES would follow when the system itself finally launched that August.

As for the NES version, it made one brief appearance at January 1991’s Winter Consumer Electronics Show. Outside of a small handful of players doing focus tests around this time, this was the only time anyone outside of Nintendo had seen this version of the game. Until now, this brief segment from an American television series called Video Power was the only footage anyone had ever seen of the game.

The only time the NES version of SimCity was seen outside of Nintendo was at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in January of 1991. This footage from the American television show Video Power was, for twenty-six years, the only known footage of the game.

Sometime after this, we don’t know exactly when, the NES version of the game – still left incomplete – was quietly cancelled, and wouldn’t be seen again by the public for twenty-six years.

NES Prototype Find

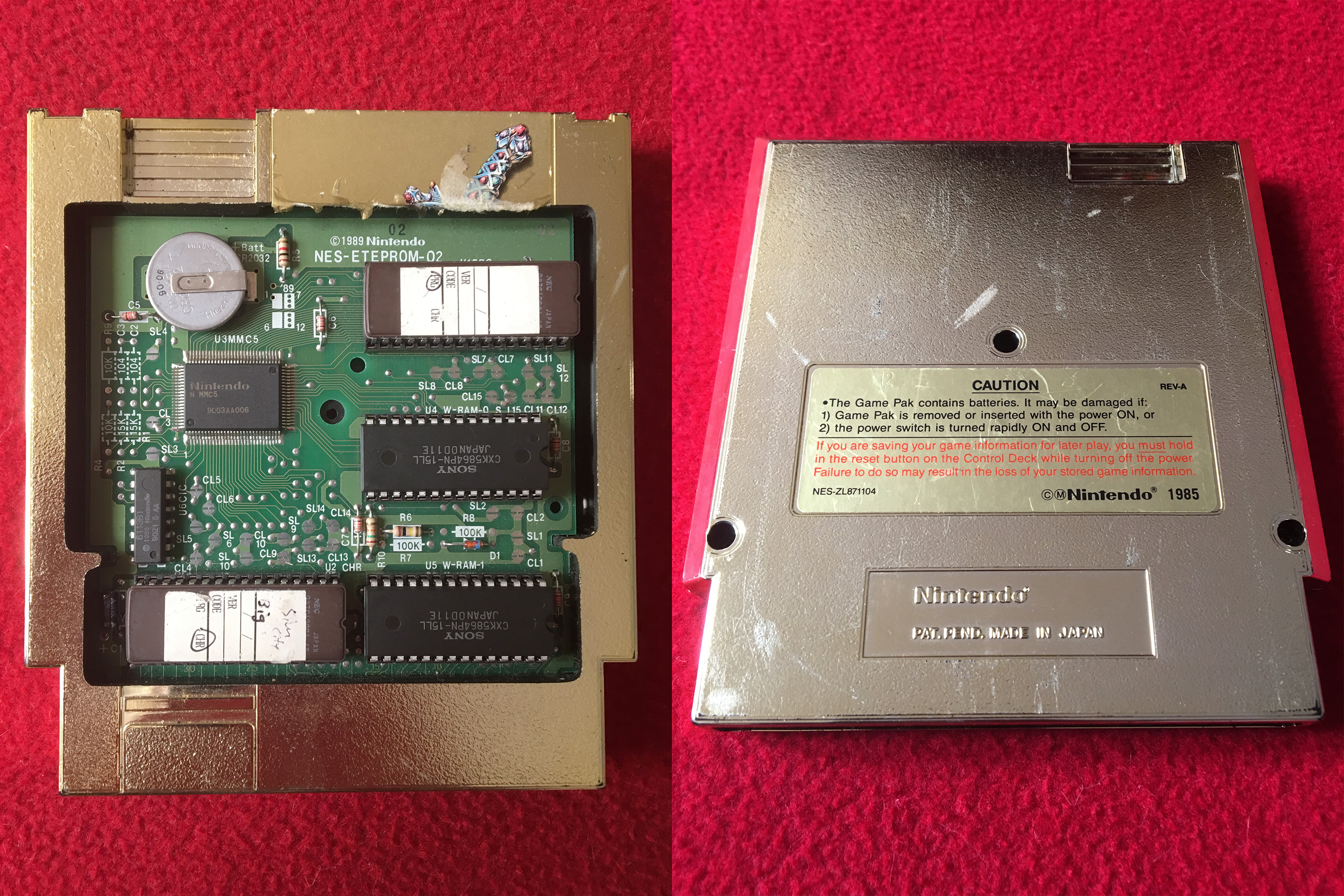

In 2017, two playable prototype cartridges of the NES version of SimCity surfaced, when their owner brought them into a used game shop in the Seattle area. This was the first time the game had been seen by the public since its showing at CES.

Unreleased games like these can be high-ticket items in the collector community. This is only compounded by it being a game made internally by Nintendo. Because of this, the original owner brought them both to the largest vintage video game collector show, Portland Retro Gaming Expo, to entertain offers. Ultimately, one of the cartridges was sold to a private collector, while the other remained with its original owner. And thanks to a financial contribution from one of our own board members, Steve Lin, we were able to take home a digital copy of the game to examine.

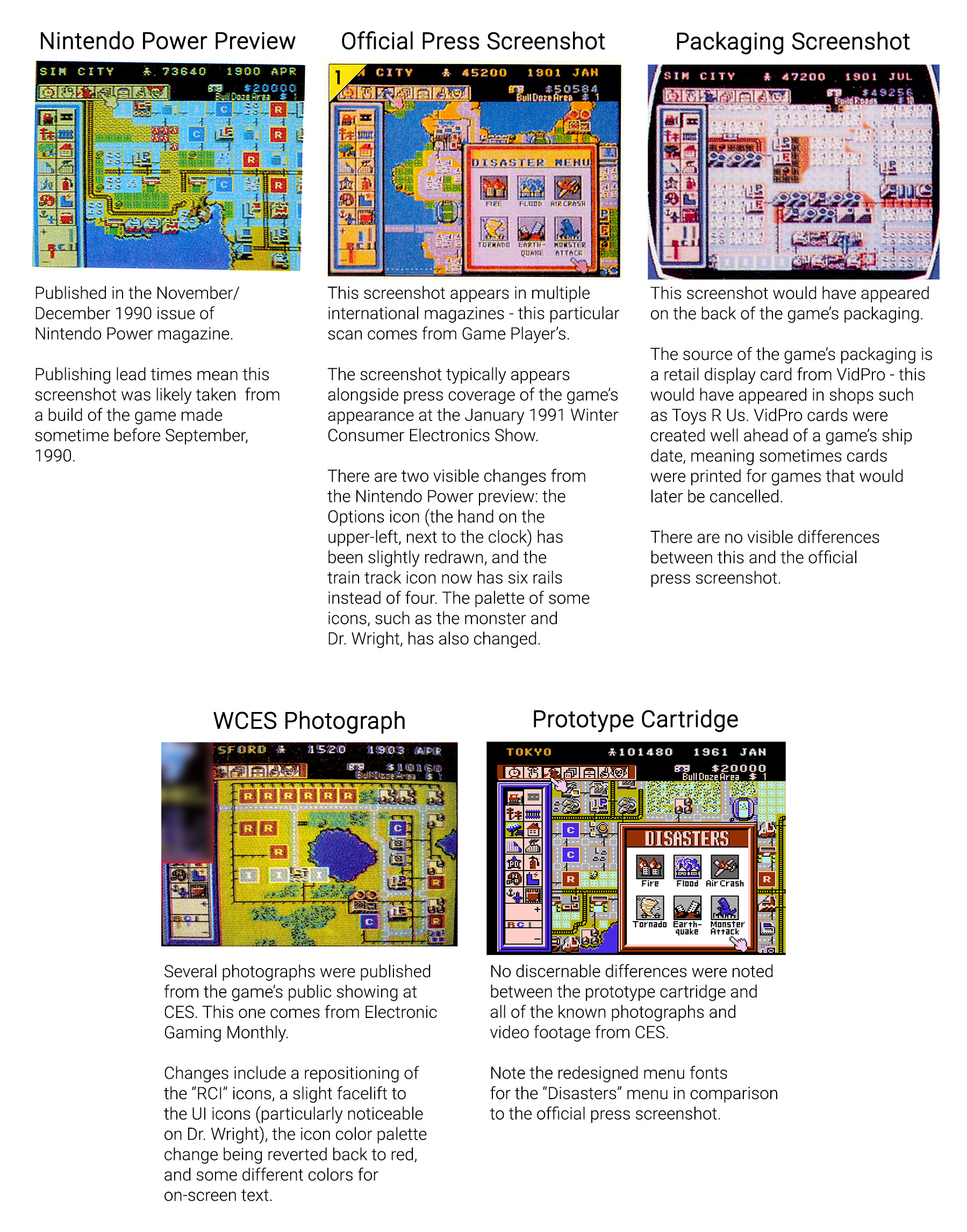

During the show, we were able to confirm that the data on both cartridges is 100% identical, byte-for-byte. Further, we noted that one of the cartridges had a build date on its front label: December 20, 1990. A person familiar with the game’s development later explained to us that this particular cartridge was used to demonstrate the game to focus test groups. And given the date, it’s not unreasonable to assume that this is the same exact version of the game that was used at CES just a couple weeks later.

Examining the Game

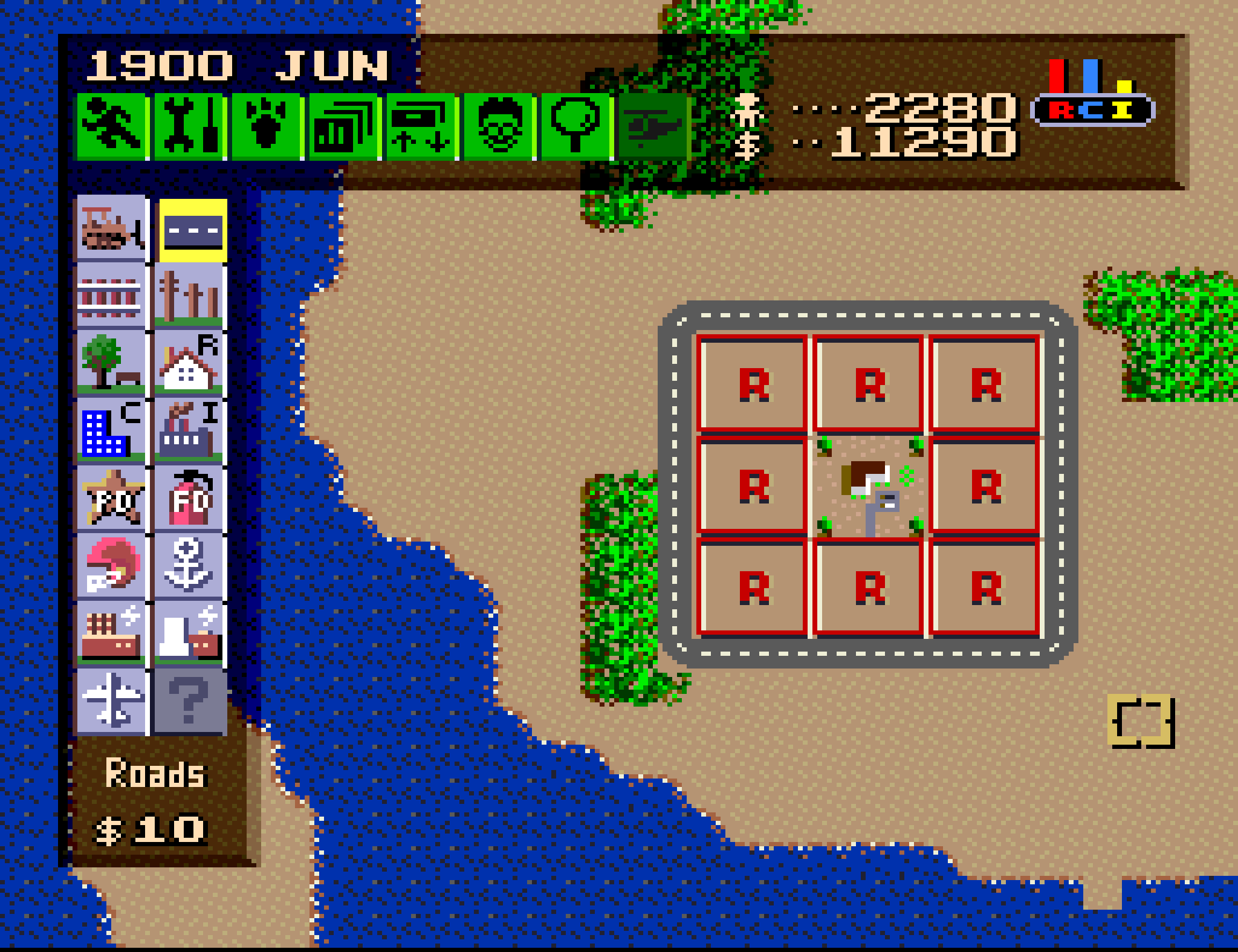

In its February, 1991 preview, Nintendo’s official in-house magazine, Nintendo Power, said that the differences between the Super Famicom and NES versions of the game “will be a matter of graphic detail only,” and having examined the game thoroughly, that’s mostly true. The core gameplay remains largely the same as the Maxis version, and the majority of the features added for the Super Famicom version of the game are present here – albeit some of them in skeletal or rough draft form.

To cut to the chase: This prototype is obviously not a finished game, as there are critical bugs, typos, and missing content, but the majority of the game’s features are intact in one form or another and the game is completely playable. Given the cartridge’s intended purpose, this shouldn’t come as a surprise. The game was never meant to be played outside of a controlled environment, whether it be a focus test with Nintendo employees present, or, as we suspect, a trade show, so there was no reason for it to be completely polished. The developers never anticipated historians somehow accessing this game nearly 30 years later and tearing it apart. They probably didn’t even expect anyone to play it for more than a few minutes! While theoretically players of this cartridge at the time could get far enough into the game to start noticing its flaws, this was extremely unlikely.

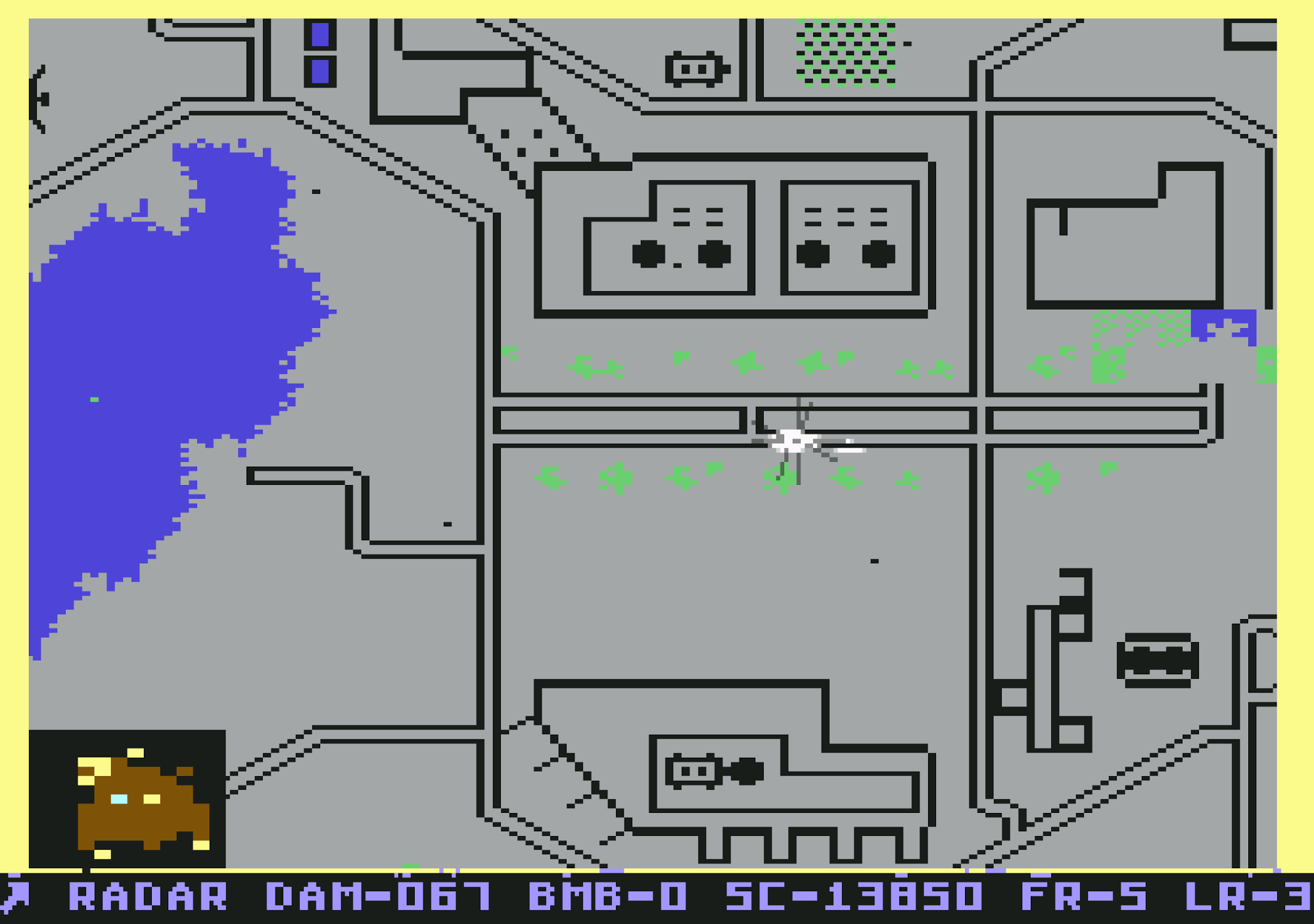

From a gameplay perspective, the most unique aspect of the NES version of SimCity is the size of its tiles. Rather than a typical tile (say, a residential zone) being a 3×3 grid, as they are in the original PC versions and the Super Nintendo version, NES zone tiles are 2×2. However, the Present tiles – the unique reward buildings added to the Nintendo versions of SimCity – are 3×3, meaning traditional strategies like building “donuts” will not work in the NES game.

The biggest surprise in the prototype was its completely unique soundtrack by Soyo Oka, the composer of Super Mario Kart and Pilotwings, among others. While Oka also wrote the music for the Super Nintendo version of SimCity, she composed her tracks uniquely for each platform. In fact, only one track, the “Metropolis Theme,” is common between the two versions. She was obviously attached to it, as she was once quoted in an interview as saying that this specific track was one of her best compositions.

What’s Here

Let’s start our examination of the NES prototype by showing what it has in common with the Super Nintendo version. As we go through these, it’s worth keeping in mind that the majority of the NES version is believed to have been developed prior to starting over on the Super Nintendo. This is not a 100% confirmed fact, but it’s how Soyo Oka remembered things in an interview. A source familiar with the game’s development also independently told us this was their recollection, and even provided some vintage documentation that seems to back this memory up.

First, the title screen itself. Both feature a similar design, with Maxis’ original SimCity logo floating over a thriving city at night. The Super Nintendo refresh flexed its muscles by having the city scroll.

The in-game UI shares what more or less amounts to the same layout, with some minor rearrangement in the Super Nintendo version. https://www.youtube.com/embed/kB0iigd6Nys Dr. Wright’s original NES appearance saw him wearing the neck tie seen in the character’s American marketing art. This character design was never seen in a commercially-released game.

Dr. Wright is here, and has a lot of the same animations as he would later have in the Super Nintendo version, along with many similar messages. Remember the regional design differences noted above, with Wright’s bowtie changing into a necktie? Look closely: the NES version uses the American design of the character, while the SNES game – even in the U.S. – uses his Japanese design.

The new bank loan mechanic is in both versions, and behaves exactly the same way. Although in the NES version, we’re treated to a unique sprite of what must be the bank’s manager, giving us a tiny glimpse into what other people must look like in Dr. Wright’s world.

And finally, the majority of the quality-of-life improvements that are unique to the Super Nintendo version made their debut here. The color palettes change with the seasons, presents are awarded when reaching certain milestones, and as the player’s city grows, so does the complexity of the game’s soundtrack.

What’s Different

As you can see, most of the new core features added to the Super Nintendo game were present in the NES prototype, but there were also some features that are exclusively in this version.

There’s a very EarthBound-like feature completely unique to the NES version. When creating a new city, the game asks you to type your favorite word, not explaining why. As the game progresses, the word players typed in makes a surprise appearance as the name of their “sister city.” It’s a very Nintendo touch.

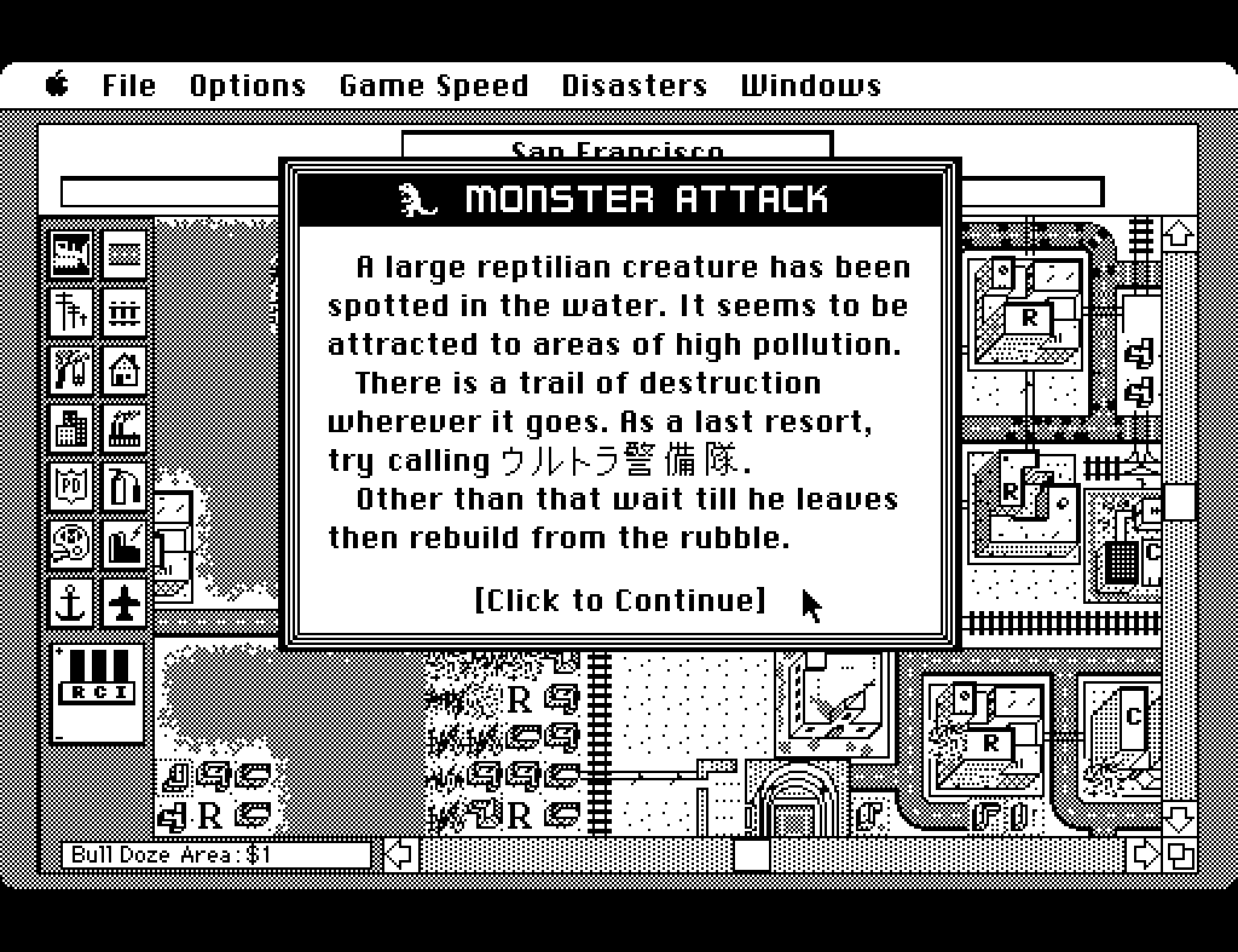

There are still a few elements in the NES version specifically that harken back to the original Maxis release for the Macintosh, which Nintendo’s developers were clearly referencing when making this port. Check out the UI for the budget screen, which is practically identical, down to the hourglass and the giant Mac-like button to click on the bottom.

While the SNES saw a similar screen, what’s unique in the NES game is its speech samples. Just like in the Mac version, the NES game plays a sample when a helicopter floats over heavy traffic, or when a monster is on screen. These samples actually eat up a surprisingly large amount of ROM space.

Speaking of the monster, it’s still a generic beast in the NES game. On the Super Nintendo, this was changed to Bowser, from the Super Mario Bros. series.

What’s Missing

On the flipside, some features that made it to the Super Nintendo are not present here. For one, anything that used the Super Nintendo’s sprite scaling and rotation features, such as the magnifying glass, just aren’t present on the NES.

There was also a unique level on the Super Nintendo: once players completed all six scenarios, two new ones opened up, including a UFO attack on Las Vegas. That scenario was not present in the original Maxis release, though UFOs would make appearances in subsequent sequels.

While this feature is technically in the NES game, the city scenario is a placeholder, with no UFO ever appearing…though if you dig into the ROM, the tiles are there for it, they just never get called. A disassembly of the code reveals that there isn’t even a function in the game to call for them yet, they’re just art tiles waiting to be programmed into the game.

What’s Broken

Not only is the game is unfinished, we were able to confirm with an inside source that the game was NEVER finished, so what we see here is probably the best we could ever hope to see. Just in case, we closely examined every published promotional screenshot of the game, including those found on what would have been the game’s box art, and all of them appear to be from even earlier versions than this. If the game got any further along than the data on this prototype suggests, it was never shown to anyone. This appears to be the last build of the game that Nintendo’s developers in Japan ever sent to the United States.

One big core problem with the prototype is in its math. Land value just doesn’t seem to function properly, especially with the presents. In the Super Nintendo version, presents would increase the land value of the tiles in its vicinity. Here, they don’t seem to do anything, which means that from a strategic standpoint presents work against you, as you’re wasting valuable tile space for no benefit. The game is still completely playable, but fans of the Super Nintendo version may notice their cities growing much slower, and sometimes declining for no observable reason.

One bug that may actually be intentional for the sake of the demo is that it’s possible to receive infinite money. In other versions of the game, if your spending for the year exceeded your collected taxes, you’d have a negative amount of money in the bank. In the NES prototype, if you owe the bank more money at the end of the year than you have, your funds roll over into a huge positive sum, completely eliminating any challenge.

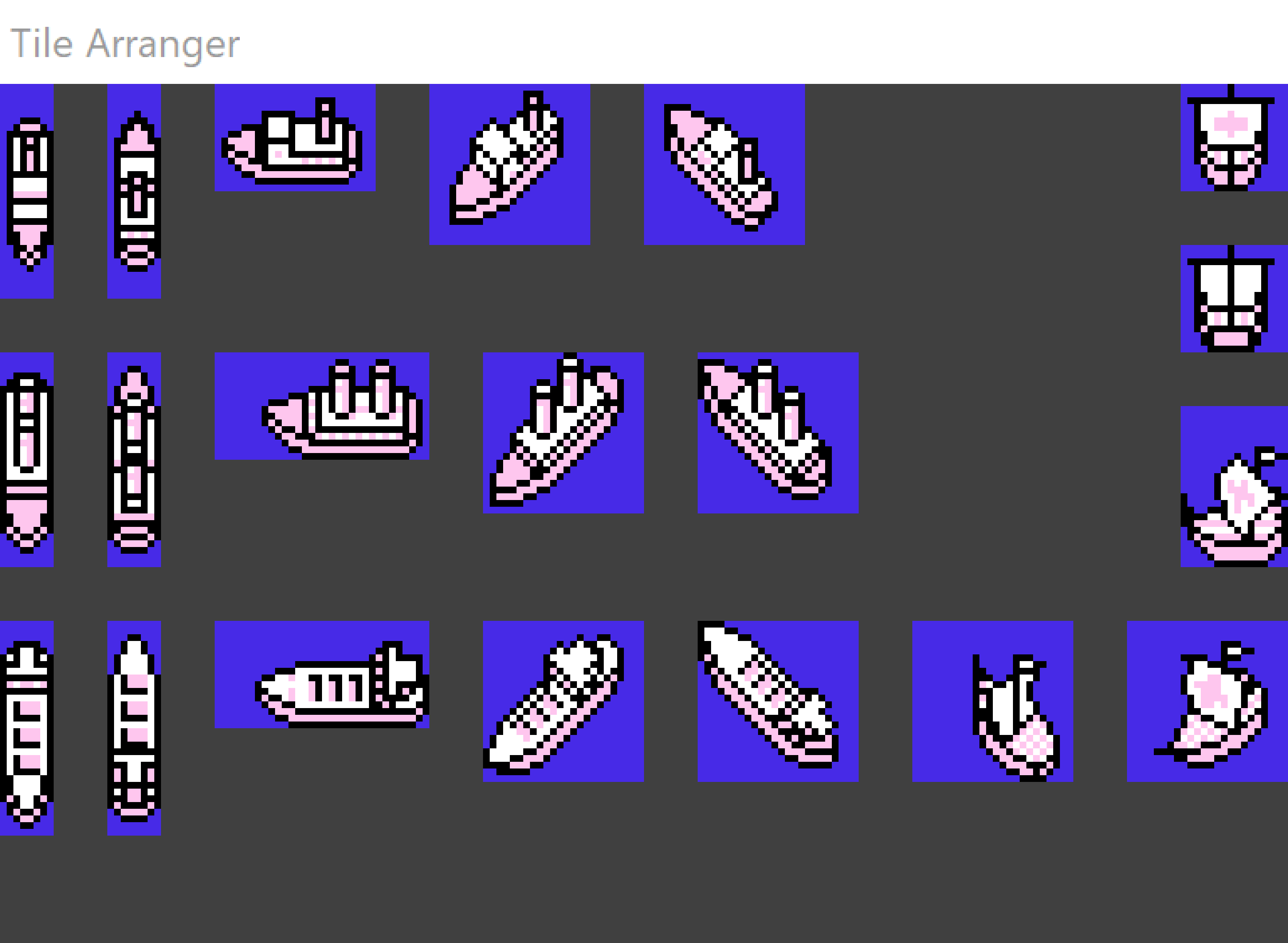

Something completely absent in the NES version of the game is boats. Normally, when players build a seaport, boats start floating around in the city’s water – and even evolve in appearance depending on the in-game year. In the NES prototype, the boat tiles are mostly present and accounted for, and there’s even some partial movement behavior in the game’s code, but the boats never appear through normal gameplay.

The prototype’s Practice scenario, despite having a clear goal, has no win or lose state. Like the boats, code exists in the ROM itself to trigger these win or lose messages, it’s just never called by the game. This might have been intentional – perhaps the developers commented this functionality out for this build of the game, so that the game could run indefinitely without being interrupted.

Digital Archaeology

And on that note, there’s actually a lot of unused information in the ROM itself that is never accessed through normal gameplay. There may be more unused art in this ROM file than in any known commercial NES game. This is really exciting. Not only do we have a rough draft of the Wright-Miyamoto collaborative take on SimCity, we also have glimpses into even earlier ideas.

For example, here’s a unique present: the Botanical Garden. Unfortunately there doesn’t appear to be any code left in the game to tell us how this might have been earned, so we’ll probably never know, but the tiles themselves are completely intact. This might have been one of the earliest presents conceived, as its name appears among a handful of other present names in a completely unused section of tile data, suggesting an earlier implementation of the Presents mechanic.

Speaking of unused tiles, there are quite a few sports structures present, including a couple baseball stadiums and what appears to be a horse track. There actually isn’t animation or color palette data for these tiles, so what you’re seeing here are my best guesses for what they’d look like.

There are also two unused airport tiles…perhaps they were meant to evolve with time, as the airplanes themselves do? We’re not sure, as no version of the original SimCity to my knowledge has varying airports.

The Mayor’s House present has three unused versions too. In the Super Nintendo game, your house grew along with the city’s population, so it’s likely that was the intended use here too.

Four unused Dr. Wright animations are present in the ROM, and can be accessed by hacking the game. All four would go on to appear in the Super Nintendo version. Two of these flicker badly on a real NES due to its limitation of showing only eight sprites per scanline – this restriction was removed via emulation for the sake of this video.

The SimCity Digital Archive

There’s actually a whole lot more to dig into in the game’s code. Friend of the foundation and NES expert CaH4e3 (pronounced “Sanchez”) has spent several months doing a complete, commented disassembly of the game, along with extensive documentation of cut features, oddities, and other findings from his extensive archaeological dig. He even fixed bugs and started implementing cut features, including the lost boats.

And hey, remember how I said that one of the prototype cartridges was sold to a collector? That’s our friend Christian Deitering, who has created an incredibly extensive guide for the NES prototype at GameFAQs, among other places.

And finally, the digital ROM file itself was uploaded to the internet by Steve Lin, and should be playable on just about any modern NES emulator that supports games running on MMC5 hardware.

Conclusion

As you can see, the recovery and study of artifacts such as these is only made possible through a group effort. From the archiving of the game to the interpretation of its worth and everything in-between, the story of SimCity for the NES – a game that could easily have been lost forever – could only be told thanks to the combined work of archivists, historians, collectors, and financial benefactors working together.

Special thanks to Steve Lin, Christian Deitering, CaH4e3, LuigiBlood, Chris Covell, Kelsey Lewin, Patrick Todd, Adam Patrick Murray, and especially to our ongoing patrons for making this all of this possible.

If you’d like to help save video game history along with us, head on over to our donation page to learn how you can get involved. Everything we do here is publicly funded by people just like you, and every single dollar we receive helps make it all possible.