In 1976, Exidy’s Death Race was condemned by journalists and politicians and pulled from arcades; the first time a video game caused a moral panic. In this short video, we take a look at what happened, and how these events laid a path that subsequent controversies would follow for decades thereafter.

After creating the video, I had a few outstanding questions and leftover research materials that didn’t comfortably fit. So, with the help of some of the people who worked at Exidy at the time, let’s dig a little deeper into the story of Death Race.

Where did Death Race come from?

Death Race wasn’t an original design. It was a minor modification of an earlier (and much less successful) machine: 1975’s Destruction Derby.

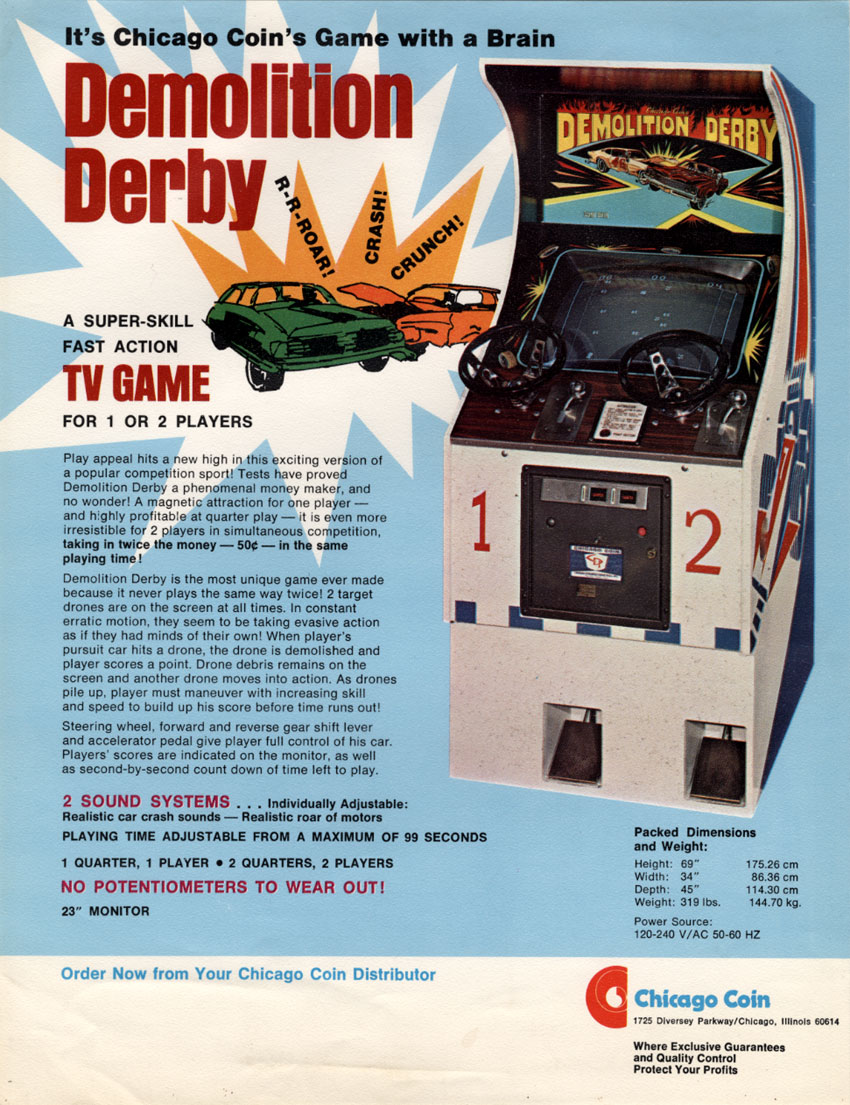

Exidy were a minor industry player with a limited reach. Struggling to find buyers, they licensed Destruction Derby to Chicago Coin, a company with 44 years of pinball and coin-op experience. Exidy would manufacture the machines (re-branded, with a sportier cabinet design, as ‘Demolition Derby‘), and Chicago would distribute them through the channels they’d built over the decades.

Or at least that’s how it was supposed to go. Unfortunately, the timing of the deal coincided with Chicago running out of, er, coin. (The company would collapse two years later.) Contractually prohibited from selling the machine themselves, but receiving little in the way of royalties, Exidy decided to change the game just enough to bring it to market as a new product. Howell Ivy explains the process:

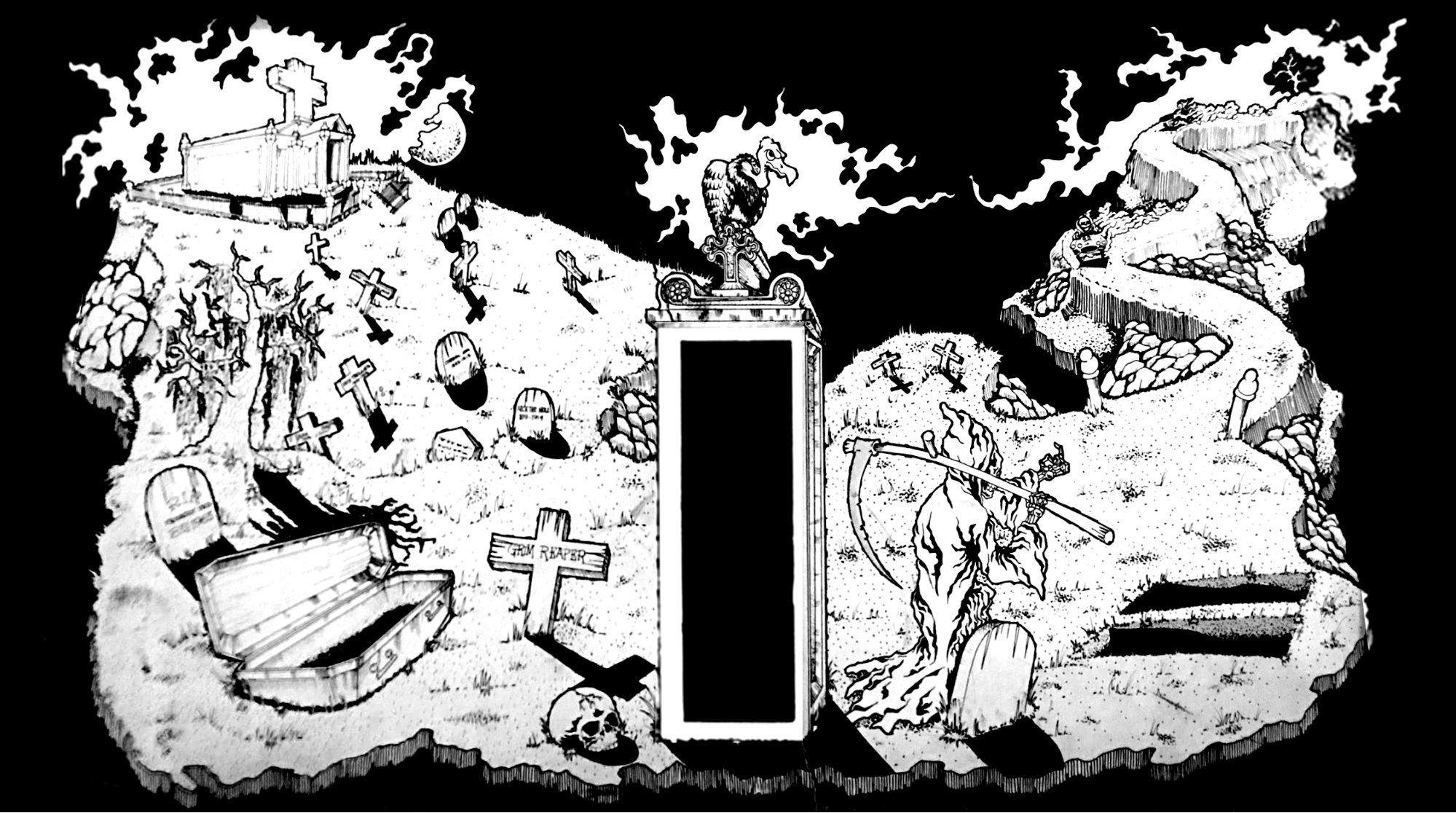

I made modifications to the PCB by changing the image memories and audio circuits to create a different game utilizing the same PCB. All the PCBs at that time were dedicated and hard logic without microprocessors or programs that could be changed. So image memory and analog components changes could be the only thing that could be changed to make the PCB a different game. Any other choice would be a completely new designed system, which would take too long. So we changed the cars to gremlins, crashed cars to crosses, and crash sounds to screams.

Then all they needed was a new name and cabinet design, and Death Race was ready to sell.

Who worked on the game (and where are they now)?

Credits for early arcade games are often undocumented, their makers denied recognition for their work. I tried to identify as many Death Race contributors as I could; here’s everything I was able to find.

The boss: Pete Kauffman

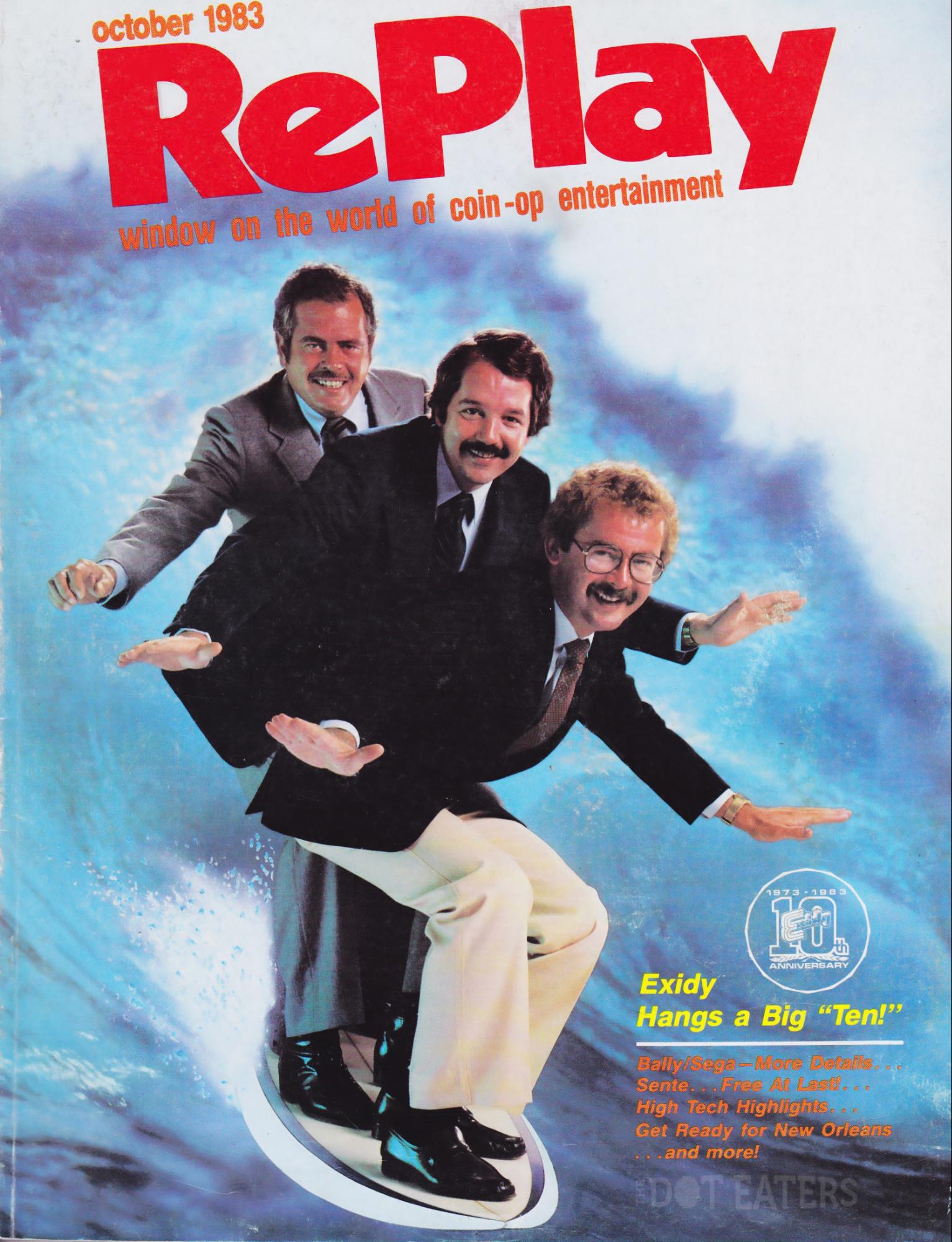

As with most of Exidy’s creations, it seems founder Pete Kauffman gave the green light to both Destruction Derby and Death Race. Described by Steven Kent as “a very quiet man”, Kauffman was the CEO of Exidy for the lifetime of the company, from its formation in 1973 through to the decline of the company’s arcade business and the pivot to redemption games in the 1990s: in total, an impressive 23-year tenure.

Kauffman passed away in 2015.

The Destruction Derby engineer: John Metzler

Exidy’s first engineer, John Metzler, had been a colleague of Kauffman’s at their previous employer, Ramtek. When he founded Exidy, one of Kauffman first hires was his former co-worker. Metzler likely designed the original Destruction Derby hardware, being the only engineer in the company at the time. But before Death Race was released, he departed to run his own electronics business.

After that, documented details of his life become scarce, but I heard from two sources that he sadly passed away a few years later.

The Death Race engineer: Howell Ivy

The conversion of Destruction Derby to Death Race involved both new engineering and new art. Handling the former was ex-USAF instructor Howell Ivy, another Ramtek alumnus. Though (as he explained above) he merely modified an existing design to create Death Race, he engineered many historic games during his time at Exidy, including Circus, Car Polo, Star Fire, and Chiller. He also designed the Sorcerer, an early home computer, in 1978.

Beginning in 1986, he spent eighteen years as an executive at Sega USA, overseeing production of many now-classic arcade games. More recently, he served as the Chief Architect of the ISS Partner Program at Valley Christian Schools in San Jose, California, an institution he still works with today.

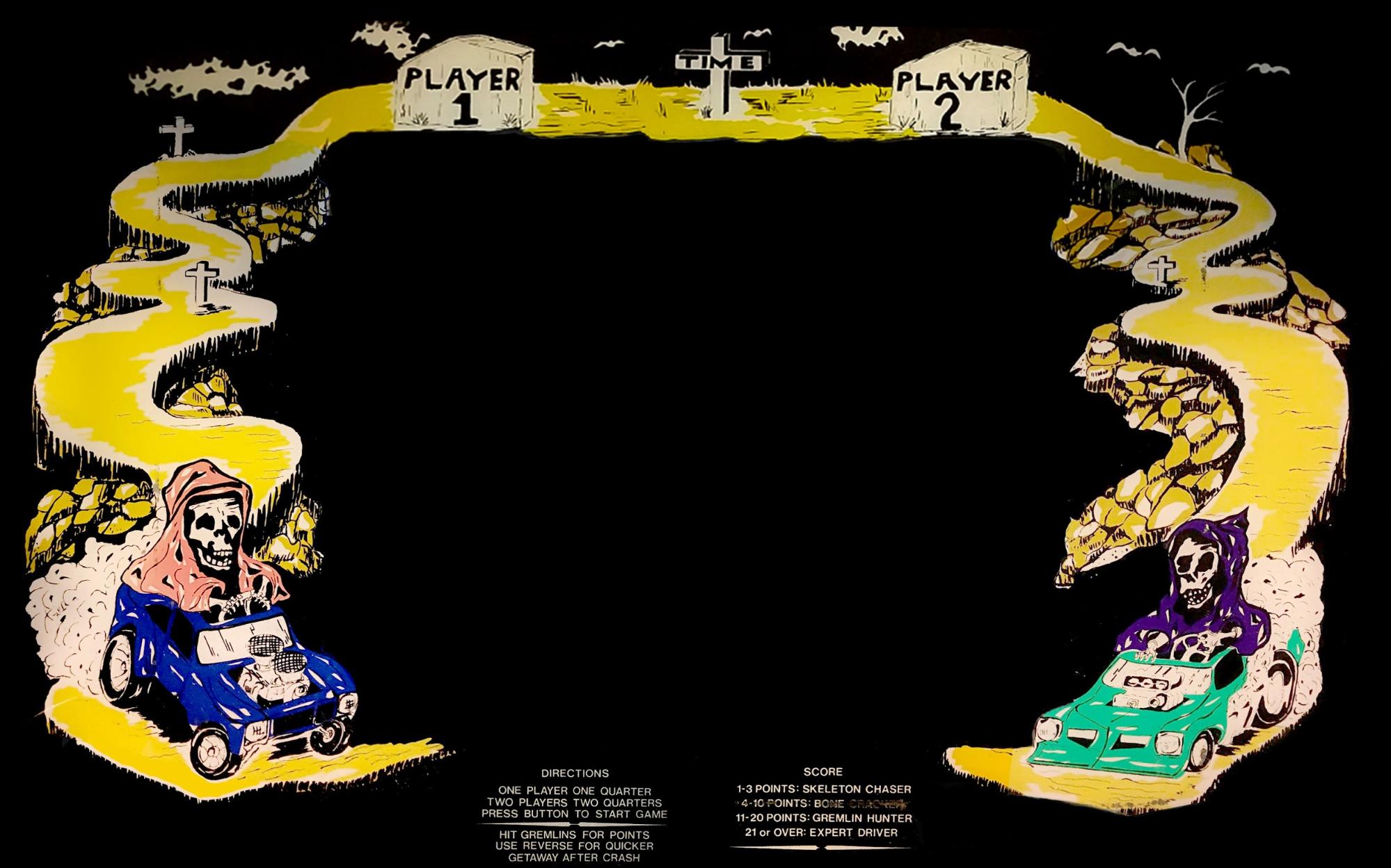

The artist: Pat ‘Sleepy’ Peak

Death Race’s striking cabinet artwork was created by Pat Peak, who went by the name “Sleepy”. He created several other marquees for Exidy (and others) at around the same time, but I was unable to learn anything of Peak’s post-Exidy life.

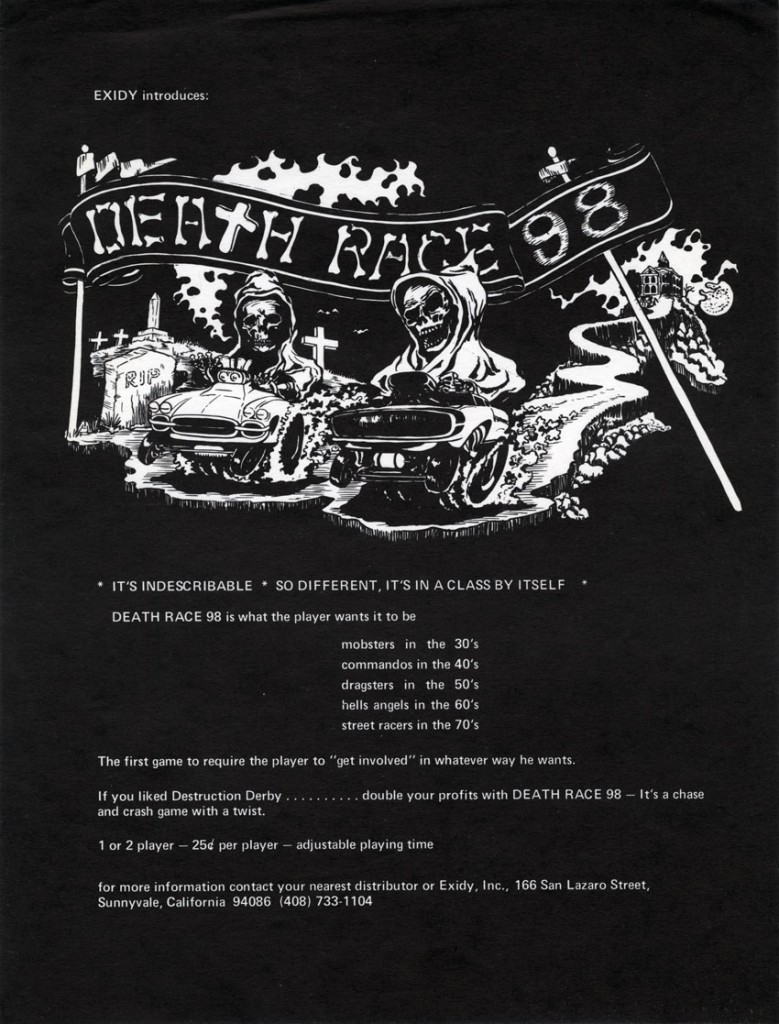

The spokesperson: Paul Jacobs

Paul Jacobs was Exidy’s head of marketing. Hired shortly after Death Race’s release, he immediately found himself in the middle of a media circus. Most of his television interviews prove too elusive to find, but he makes an appearance in this stock library clip: https://www.youtube.com/embed/KIxx_YtBsG8

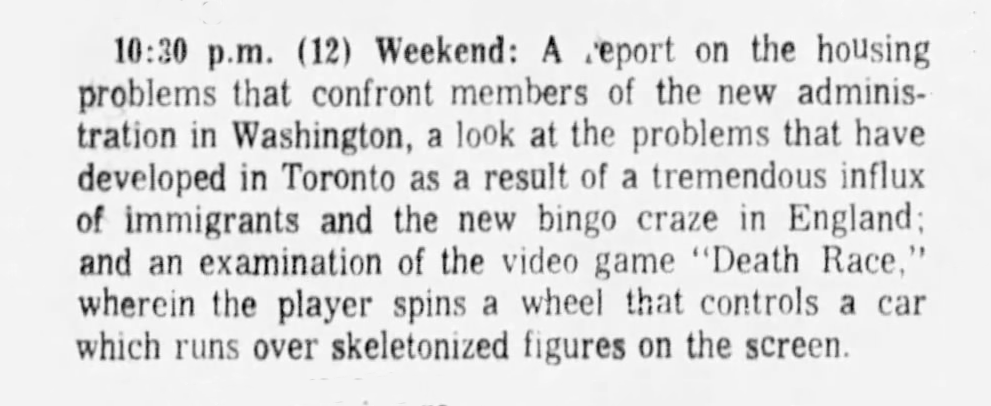

One notable Jacobs appearance, and key piece of Death Race history, was an eight-minute segment on a Saturday night NBC current affairs show in January 1977. My inquiries to the NBC archives went unanswered; I hope that eventually someone will be able to find and share this historic piece of television.

Jacobs followed his tenure at Exidy with a long career in executive roles at some of the major players in the arcade and coin-op industries, including SNK, Data East, and Capcom. A career rundown can be found on Ethan Johnson’s site The History of How We Play.

How many Death Race cabinets were manufactured?

There’s some uncertainty. That the game sold poorly before the controversy, and better afterward, isn’t in dispute. But different sources give different numbers.

- Steven Kent spoke to Pete Kauffman for his Ultimate History of Video Games, and quotes him as saying 1,000 machines were sold in total.

- In July 2016, former executive Larry Hutcherson spoke at an Exidy reunion panel at California Extreme. In response to a question, he spoke of an initial run of 5,000 machines, plus 1,500 more after the bad press.

- Paul Jacobs is quoted as saying the initial shipment, in the three months before the controversy hit, was only 200 machines, with that number rising to 3,000 (including 1,000 overseas PCB sales) after the game achieved notoriety.

- Keith Smith’s site quotes a programmer, Ed Valleau, recalling that the first run was 1,000 units, with two subsequent runs that together saw another 1,000 built.

Jacobs and Valleau’s figures being in rough agreement, I’m inclined to believe the total number of cabinets produced was probably only around 2,000 plus some extra PCBs, and that Hutcherson’s answer, extemporaneous as it was, was mis-remembered or misspoken. Pete Kauffman’s response could imply a large number of machines were built but not sold, but seems more likely to also be a minor mistake in recalling a decades-old event.

But in any case, perhaps the sales numbers are the wrong question to ask about Death Race. Howell Ivy argues that the biggest effects were more indirect:

The sales did increase slightly, however the most important aspect was raising the name “Exidy”… to a national recognized level. This resulted in an overnight increase in our Distribution Network and customers. The game gave us the shot in the arm to get our small company over the difficult early growth phase and be a competitor with the big guys.

How can you play Death Race today?

Not with an emulator, unfortunately. The game was hard-wired into the PCB; there’s no CPU executing instructions, and no software to dump. Neither MAME nor DICE (the Discrete Integrated Circuit Emulator) currently implement the game.

The original cabinet, with its dual steering wheel and pedal controls, provides the authentic experience. To partake, prepare to make a pilgrimage to one of the few remaining working machines accessible to the public, like those at Funspot in New Hampshire, Daytona Arcade Museum in Florida, Musée Mécanique in San Francisco, or the Galloping Ghost Arcade in Illinois. (Readers outside the USA may find the expedition a costly one.)

Otherwise, the best options are the two free indie versions of Death Race that run on Windows PCs: one by Rogue Synapse, the other by Fabien Brooke. Neither is perfectly accurate — they’re remakes, not facsimiles — but for now, they are the closest you can get without leaving the house.

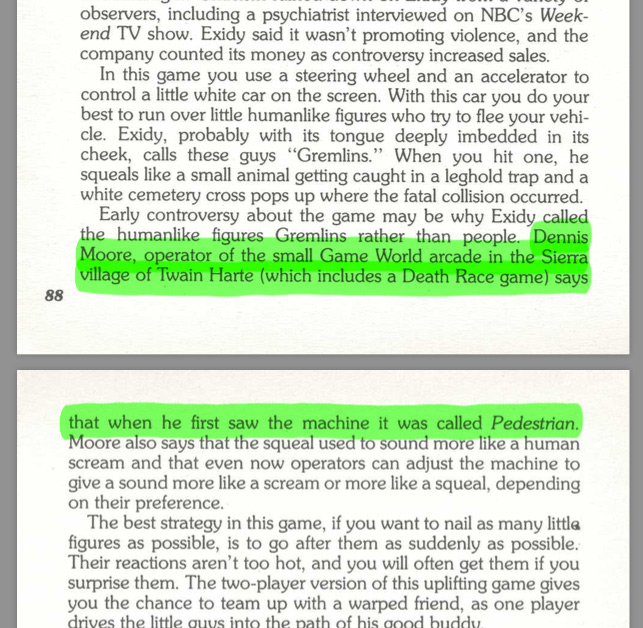

Was the working title Pedestrian?

The claim: while under development, Death Race was known as Pedestrian. The statement has been circulating for many years, usually without any citation. It even made it into a 2008 episode of G4’s animated comedy Code Monkeys, featuring a bizarre cameo by Howell Ivy that obfuscated the truth even further.

Historians generally write off the claim as an urban myth, but let’s see if we can dig a little deeper.

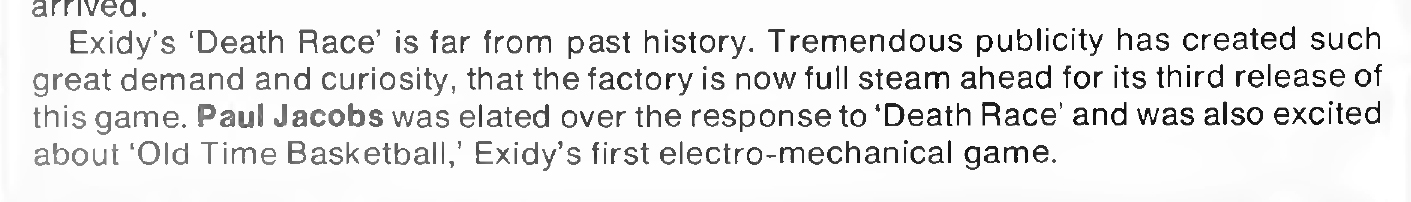

We know that the game had a different working title: Death Race 98, as seen in the game’s original announcement. This title may have been too close to the movie Death Race 2000, and the number was dropped before release.

But there’s nothing in the trade press that calls the game Pedestrian, nor has anyone found any other evidence to support the claim. We can be pretty sure that Death Race was never released, tested, or announced under that name, but maybe there’s another slim possibility…

At the CAX 2016 Exidy panel, Larry Hutcherson talked about Death Race originally being a ‘goof’ project they’d made purely for their own amusement, that was never intended for release:

In an email, Larry elaborated on the nature of this early incarnation:

The very first version of Death Race was a version with new graphics that still used the Destruction Derby audio. It existed only in the lab and was never released or tested in public.

Could this early machine perhaps have been jokingly named Pedestrian?

Larry Hutcherson, Howell Ivy and Paul Jacobs all agree: definitely not. All three assert that it was called Death Race from the outset, closing the door on the last credible possibility that it was ever known as Pedestrian.

So where did this myth originate?

The source of the claim appears to be a book of arcade strategies published in 1982, The Winners’ Book of Video Games by Craig Kubey. In that book, an arcade employee is quoted as saying he first saw the machine with the name Pedestrian.

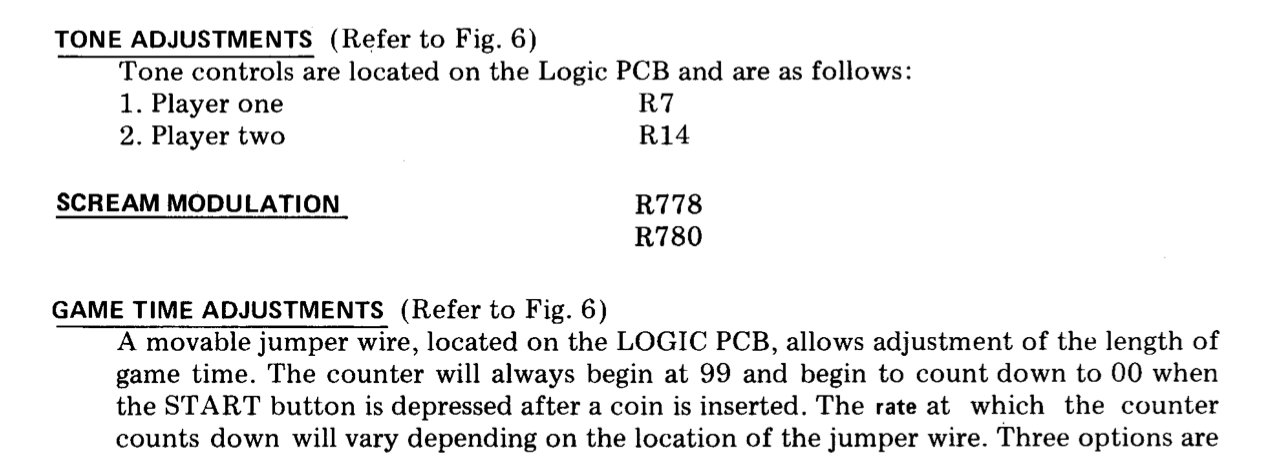

The operator’s second claim about the sound setting is given credence by the manual: configurable internal components controlled ‘scream modulation’.

But the other claim leads nowhere. However, Hutcherson suggests a possible explanation: the employee might have seen a Death Race cabinet that had received an unofficial makeover.“I have seen old games with an incorrect marquee. I’ve even seen some with paper artwork sandwiched between clear plexiglass panels. It would not be surprising to learn that someone may have created some artwork and put it on a cabinet.”

Unless we can track down the man who gave the quote (I tried, without success), our investigation must end here: not at a hard answer, but at least at a plausible explanation. Death Race was never called Pedestrian, except perhaps through one owner’s unorthodox customizations sometime before 1982.

Sources and Further Reading

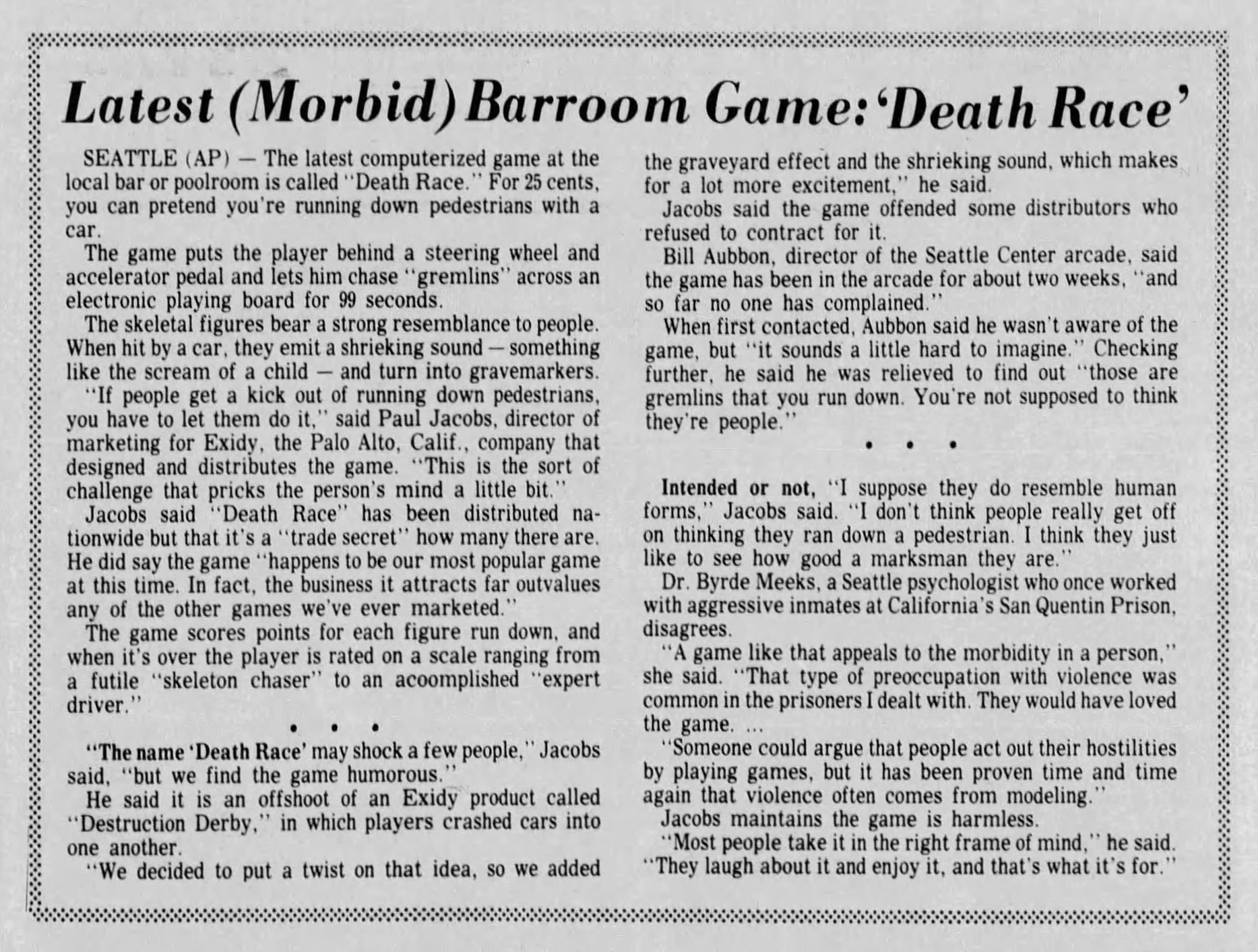

The ignition source of the Death Race controversy, several months after the game’s release, was the July 1976 AP wire article by Wendy Walker, which ran in hundreds of newspapers across the United States. Paul Jacobs is quoted. Many editors truncated the piece, cutting off the last two or three paragraphs, or sometimes more. Unlike scans already on the web, this is the full unabridged article:

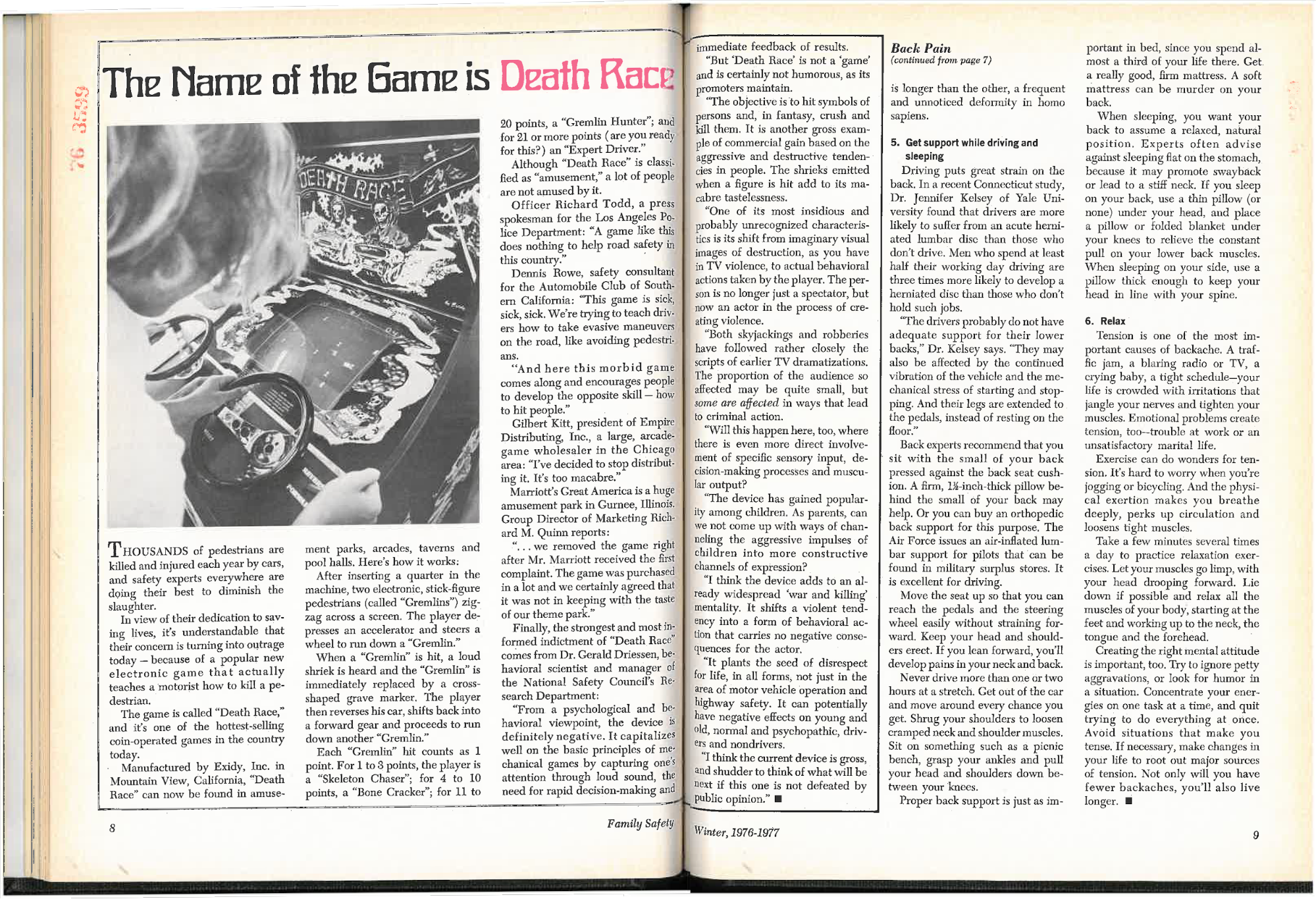

The controversy was reignited a few months later with a polemic in the pages of Family Safety, the membership magazine of the National Safety Council, a health and safety advocacy organization. Many thanks to the Council for providing a scan of this article; it’s believed to be the first time it’s ever been available on the web:

The Family Safety piece triggered another round of television and newspaper coverage, including a December 1976 New York Times article by Ralph Blumenthal.

In researching the video and this accompanying article, I drew heavily upon two excellent histories: Carly A. Kocurek’s paper The Agony and the Exidy: A History of Video Game Violence and the Legacy of Death Race, and Keith Smith’s blog The Golden Age Arcade Historian. Steven Kent’s book The Ultimate History of Video Games and Howell Ivy’s interview in Retro Gamer issue 125 provided further quotes and background.

Many thanks to Howell Ivy and Larry Hutcherson.

Chris Chapman is an amateur video producer and student of video game history. By age 35, he had saved up twice his weight in computer magazines. Follow him on Twitter at @retrohistories.