I love my job here at the VGHF, but if I had to pick one favorite task, it’s digging through people’s basements looking for game history gold. And if I were to rank these basements, among the top would be Ed Semrad’s.

Ed was a weekly game review columnist, and later, the editor-in-chief of Electronic Gaming Monthly magazine, a publication that is not only meaningful to me personally (I was a reader during Ed’s run), but historically.

If you asked me to describe Ed, the two words I’d use are “completionist” and “perfectionist.” Ed is the kind of guy who obsessively recorded every episode of every television show he enjoyed, and a not-insignificant portion of his basement, behind the Christmas decorations, is dedicated to homemade DVD box sets of recordings he made in the 70s and the 80s (and yes, every one of those shows is available in better quality now through official means, but where’s the fun in that?). Among his hobbies is fishing and radio broadcast DX’ing, which involves carefully tuning in to radio stations thousands of miles away and logging them in a journal. You can see why this guy might be into video games.

And when it comes to games, Ed must have been one of the earliest Americans to modify his consoles to output pure RGB signals, providing a much clearer picture than shlubs like me with our RF connectors or, if we got fancy, composite video signals. This, combined with his love of photography, meant that his skill taking clear video game screenshots in the days before digital capture cards was rivaled by few in his day.

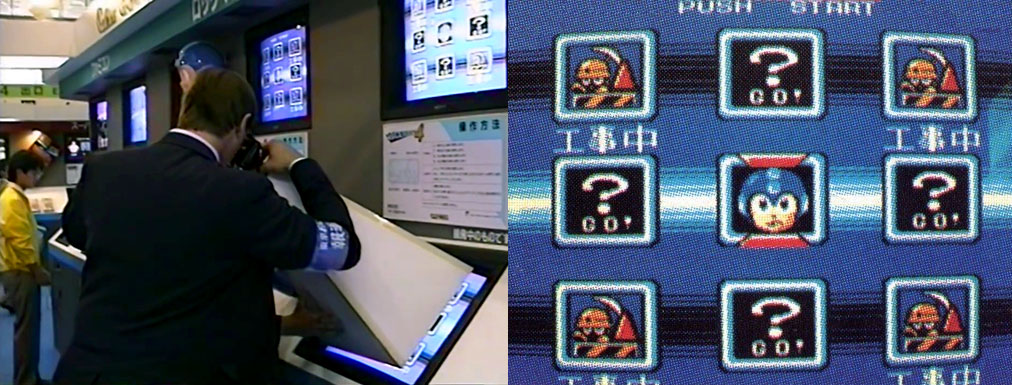

Ed’s obsessive personality made EGM a valuable resource. If a game existed and could be seen by his eyes, he had to have screenshots in the magazine. Ed was careful to catalog every game he saw at every trade show he attended. If it was playable, he snapped photographs while another editor played, with the “cone of silence” he invented and was well known for.

If there was a video loop showing footage of a game he couldn’t get his hands on, Ed patiently stood with his camera at the ready to make sure he captured it. If photography wasn’t allowed, Ed would find a hiding spot to sneak shots with a zoom lens. His office walls were adorned with photographs he’d taken of the “no photography allowed” signs he’d encountered on the job. At least once, when no one was looking, Ed re-routed a demo station’s video cables into a camcorder and back out to the TV, quietly recording an entire game demo that turned into a multi-page spread that the magazine was not supposed to have.

At the time this made EGM the source for knowing about every upcoming game, but for historians today, Ed’s obsession means that there are multiple unshipped and unfinished games whose only visual record of having ever existed came from Ed’s camera. If not for Ed, we would have no idea what these games looked like, let alone that they were ever in formal production.

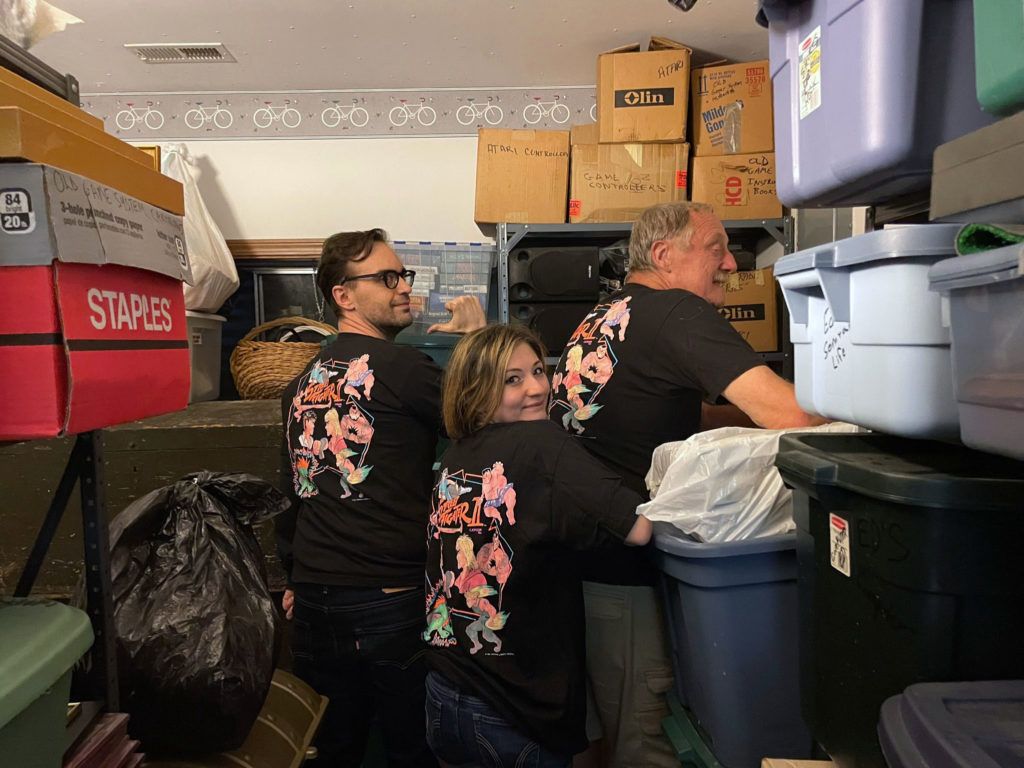

In 2021, we were fortunate enough to be invited into Ed’s home to evaluate the video game material he had accumulated during his time in the industry, to see if any of it was of historical importance. Ed wanted to keep the physical items, but was kind enough to not only let us rifle through his entire basement looking for treasure, but to also let us digitally document what was there.

You have to understand: for someone like Ed, there was little-to-no distinction between an unreleased or prototype video game and a dirt-common cartridge easily found on eBay. All of these are just…his games. So as Kelsey and I dug out plastic tub after plastic tub, we sorted his collection in realtime, putting aside anything that might contain unique data.

And did we find any prototypes, hidden away in Ed’s basement forgotten for nearly three decades? Yeah, we found a few.

As one of the few nationally syndicated game reviewers in the U.S., Ed was sent many, many games, and as you might imagine, many of them were sent before they were completed, and a few of them never made it to market at all. The data on Ed’s unreleased games for the most part was identical to the copies that have been floating around on the internet (which should come as no surprise, as that data typically came from “review copies,” all of which are typically made at the same point in a game’s development), but there were a few surprises in the lot as well.

Rather than trying to document this all ourselves, as fun as that might be, we passed the data along to the experts: Matt Reichert at AtariProtos for the Atari carts (the May 9, 2022 update…it took us a while to post this), Omar Cornut at SMS Power for the Sega Master System games, and for everything else, the inimitable Hidden Palace.