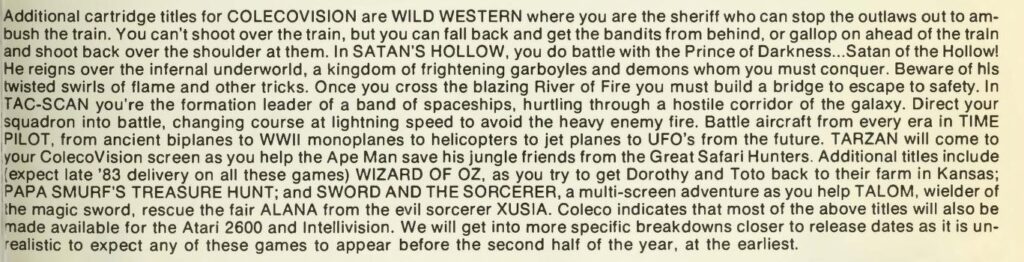

When you think about games written for the Atari Video Computer System (or 2600) today, what do you picture? Likely a home version of an arcade game, or some kind of shooter, a maze game, something that takes place entirely on a single screen. This is not the entirety of the 2600 library, though – major releases such as Pitfall!, Adventure, E.T: The Extra-Terrestrial, or Smurfs: Rescue in Gargamel’s Castle were built around worlds that extended beyond the screen’s borders, where you didn’t necessarily know what was coming next or how you’d need to approach that challenge. And among the most ambitious of these titles announced was Tarzan, to be published by Coleco for the 2600 and the ColecoVision console in 1984.

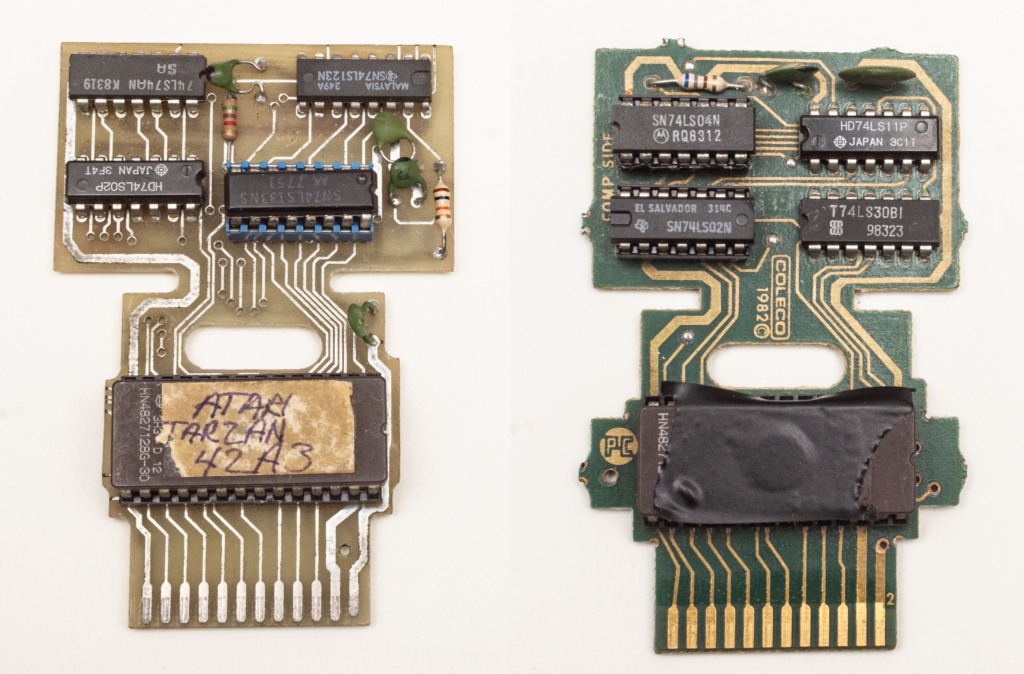

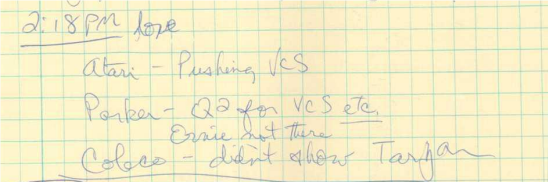

Tarzan was initially announced for as a 1983 ColecoVision release at the 1983 Winter Consumer Electronics Show, held in Las Vegas, with a 2600 port announced later that year during the summer CES for a November release. These dates slipped, with the ColecoVision Tarzan finally shipping in August, and the 2600 game announced as a second quarter release before being quietly canceled. The released ColecoVision version was fairly well-reviewed, with the newsletter Computer Entertainer praising the graphics and the varied action, noting strategy is required to clear the game. But the 2600 version faded into obscurity, considered just another project canceled due to the 1983 North American market collapse and its yearslong aftermath. In 2011 a manual for the game turned up, but the game itself remained lost. Lost, that is, until collector Rob “AtariSpot” managed to purchase a working copy of the game off of a former Coleco employee in 2022 and successfully worked with longtime Atari homebrew programmer Thomas Jentzsch to get it dumped. All 2600 games bigger than 4 kilobytes in size utilize an approach called “bankswitching” to get around hardware limitations by inserting code that gets the console to look at a separate 4-kilobyte chunk of data. This allowed for larger and more complex game programs, and Tarzan, a 16-kilobyte cartridge, is no exception. The game uses a unique bankswitching scheme, but Jentzsch was able to modify it into a standard “F6” bankswitch to make it operable on emulators and flash carts. Both versions are included with this article.

“I remember when they first came to me with the concept (of bankswitching for Tarzan), I’m like, ‘it’s gonna do what?’ Because in order to switch the banks, your software had to be in a certain place. So it landed in the right place in the other bank … once we got the hang of figuring out how we were gonna do it, it wasn’t too complicated.” – Henry Will IV, interview with AtariSpot, July 8, 2023

The Story of Tarzan

Tarzan for the 2600 was not being produced in-house at Coleco, but rather from the New Jersey-based design studio James Wickstead Design Associates (JWDA). Founded in 1969, JWDA had spent the years prior to the video game boom designing toys for Parker Brothers, including electronic games like Bank Shot and Wildfire Pinball, particularly after Mattel Electronics’ handheld Football game became a huge success. James Wickstead remembered being told by an industry friend in California that they should look into developing video games, as there were no design studios on the East Coast despite the market being hot in the early 1980s. The company took its first steps into the 2600 library when then-JWDA designer Garry Kitchen reverse-engineered the console and produced Space Jockey, a straightforward shooting game that nonetheless provided enough information for JWDA to understand the hardware. JWDA predominantly produced its console releases through US Games, but as they had a preexisting relationship with Parker Brothers and Coleco, the company designed games for those publishers as well.

“Many times, (these publishers) approached us. They had some games that already existed … they pushed us some of the games they wanted us to do for them, which we did. Basically, translating games from other systems or (the ColecoVision) into the Atari format.” – James Wickstead, interview with Kevin Bunch, Nov. 16, 2021

Wickstead said that at its height, JWDA had eight programmers, each assigned to a given project, along with a separate electrical engineering team to design any special tech needed for the cartridges. The company received a fee for each game developed on top of royalties, an arrangement Wickstead said worked out very well for JWDA and its employees even when the market ran into trouble overall.

“We worked as a team, and if somebody had a problem or anything, we would bring the team together for some time to try analyze the problem to help that person get over their hurdle.” – James Wickstead, interview with Kevin Bunch, Nov. 16, 2021.

Coleco’s game design team was overseen at that time by the late legendary game developer and designer Jennell Jaquays, who served as a design group manager. Coleco largely focused on home conversions of arcade games and utilizing existing licenses to help sell their products, Jaquays told David Craddock in 2017, because then the games had a leg up on selling themselves.

“They figured they would jump into the market by licensing arcade consoles, because another thing Coleco did was they wanted someone else to pre-sell their work. They liked licensing, and they’d already found out from the tabletop electronics they’d sold that people knew what Pac-Man was, people knew what Donkey Kong was, people knew what Galaxian was. [Consumers] liked the game and wanted to play them at home. That is the experience that, as ColecoVision designers and artists, we were expected to reproduce, and to be honest, we did.” – Jennell Jaquays, interview with David Craddock, published Dec. 4, 2017

But sometimes designers had the opportunity to work on original game concepts, too, largely when the company licensed a non-game property. In a 2015 interview with David Wolinsky, Jaquays explained that the game was licensed as part of a marketing blitz for the movie Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, released in March 1984.

Tarzan as a game was designed by future Baldur’s Gate 3 principal narrative designer Lawrence Schick, then a project manager at Coleco, which Jaquays described in an interview with Retrovideogamer.co.uk as the modern equivalent of an associate producer. Jaquays and Schick had known each other from their shared time working on materials for Dungeons and Dragons.

“I had grown up on Edgar Rice Burroughs’ stories and was eager to do the Tarzan game, especially because it was an original design rather than an arcade adaptation, and those were prized assignments. I think it’s my favorite of the games I designed or adapted for Coleco.” – Lawrence Schick, correspondence with Kevin Bunch, Feb. 18, 2024

Schick oversaw both the ColecoVision and 2600 versions of Tarzan the first few months of active development before his primary role was shifted over to Coleco’s ADAM computer, where he recalls continuing to oversee the Coleco version right up to its completion. Design documents suggest Schick continued providing some feedback, but for the most part another Coleco designer, Phil Taterczynski, a TSR veteran-turned Coleco designer like Schick, seems to have stepped in as the lead for design and feedback duties for the 2600 version of Tarzan.

The singular mandate from the Edgar Rice Burroughs’ estate for the game was that however the game ended, and no matter what happens in the game, Tarzan himself could not die. This put a serious restriction on how Tarzan could be implemented, one cleverly circumvented by making it into a timer-based title.

Schick said that typically, an original game would be designed around the ColecoVision hardware and its capabilities first before considering how to adapt it to other platforms. Since the ColecoVision was well suited for platforming games, he designed the game so that Tarzan runs, jumps, and fights through a series of obstacles from a side-view. This carried over to the 2600, which, while creaky by 1983 standards, could still handle such a game with experienced developers, as proven by Activision’s Pitfall! published in 1982.

“We took our usual approach of designing the ColecoVision game first and then adapting it to additional consoles. The CV game was a run/jump/fight side view game – we knew we could do that, and that we could port that to other platforms. It was just a matter of pushing the gameplay a bit beyond what we’d done previously.” – Lawrence Schick, correspondence with Kevin Bunch, Feb. 18, 2024

The lead ColecoVision version was produced by a small studio in St. Paul, Minnesota called 4D Interactive Systems (which Schick had worked with while at TSR, as they contributed materials for Dungeons & Dragons), while JWDA, by this point very familiar with the hardware, developed the 2600 version.

“This was our answer to Pitfall! by David Crane.” – Todd Marshall, sound designer on Tarzan, interview with Scott Stilphen, 2014

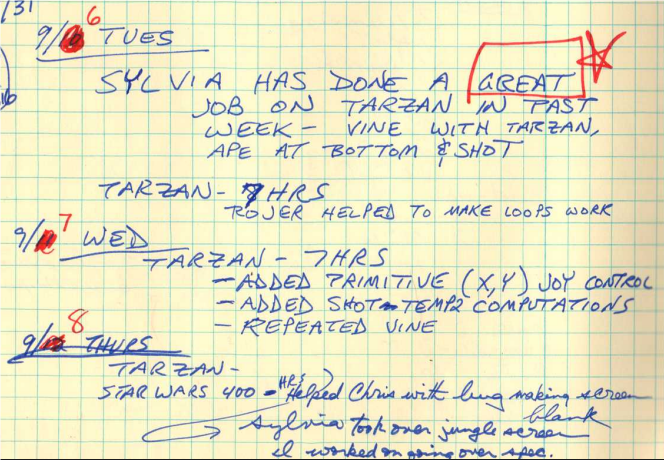

Putting together a game this ambitious on the 2600 hardware took multiple people. Leading on the programming was Henry Will IV, who previously had led on Word Zapper and Smurfs: Rescue in Gargamel’s Castle and contributed to multiple other games in the collaborative JWDA environment. Smurfs had been Will’s first experience with multi-screen game development, an experience he was able to bring to Tarzan’s development. In addition to Will, Sylvia Day and Roger Booth also worked as programmers on Tarzan, with Will in his notes crediting Day in particular for getting the vines working correctly and Booth for assisting on the game loops.

“Looking back on it, it was kind of cool to do a Tarzan game. We all watched Tarzan when we were kids. So, I mean, it was cool being able to, just in general, get these licensed cartridges and stuff.” – Henry Will IV, interview with AtariSpot, July 8, 2023

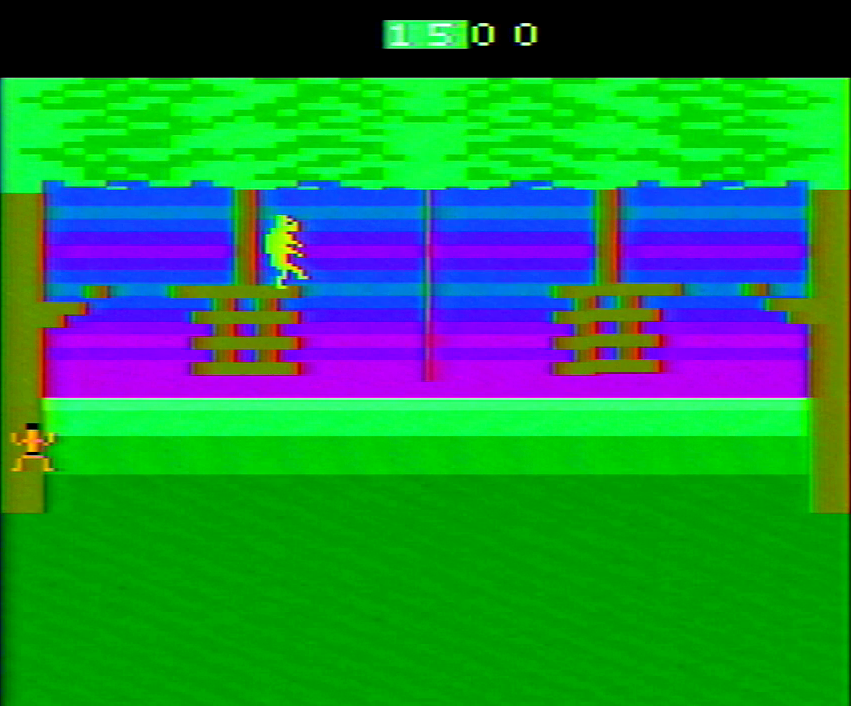

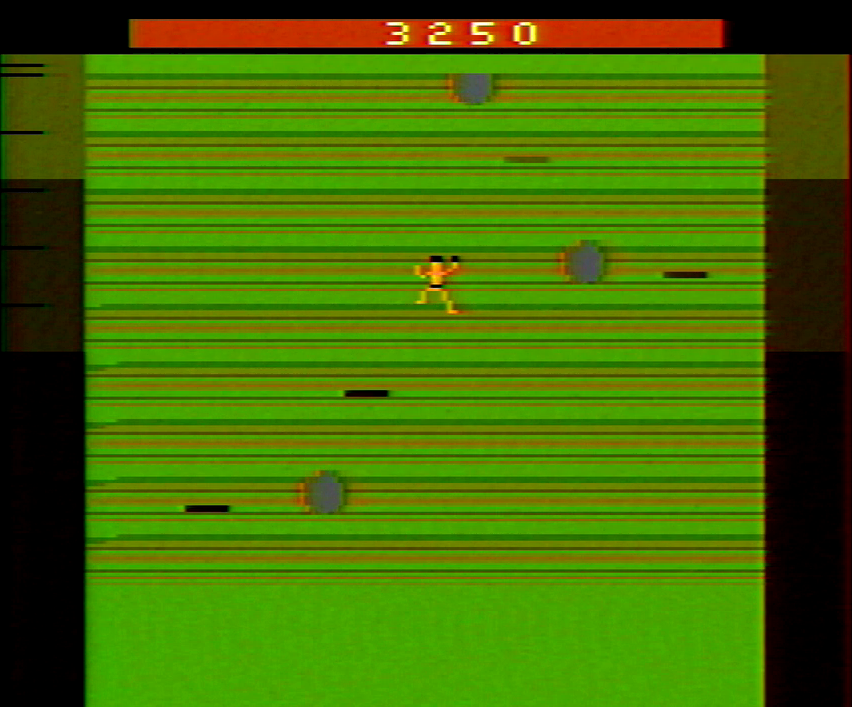

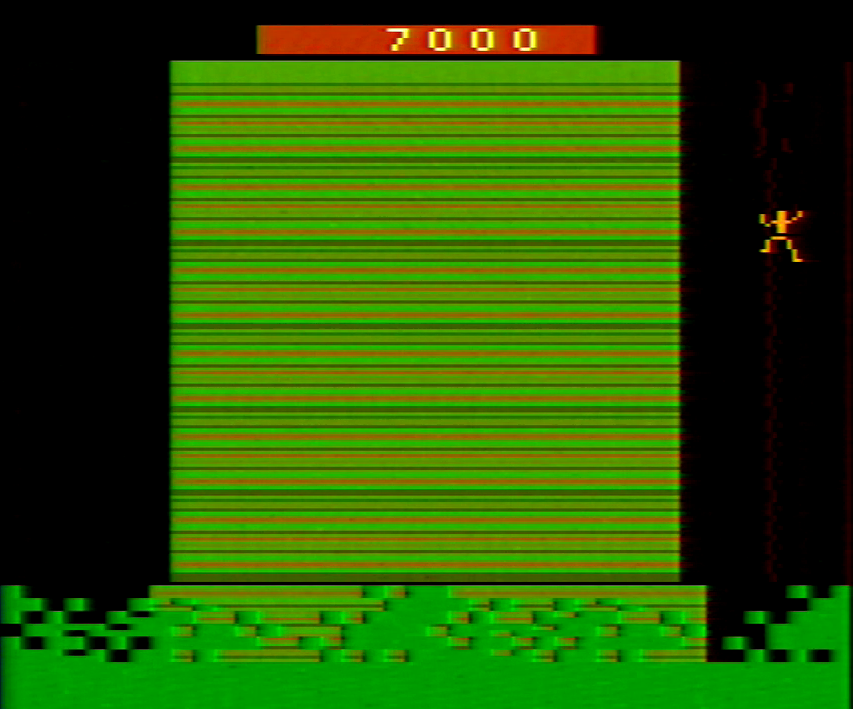

JWDA artist Robin McDaniel Ballweg helped design the game’s graphics, animation and color scheme, as she had in multiple other JWDA games. Tarzan himself is a large, multicolor character, smartly designed so his hair and loincloth do not overlap vertically with his flesh-toned body – a limitation of the 2600 hardware – and while poachers and apes are all large, single-colored sprites, they are nonetheless legible to be what they are. In the dumped build, the game effectively uses the 2600’s color palette to paint the jungle imagery, from the thick treeline to the dusky sky seen in the distance – whether or not she was responsible for these elements is unclear, but they create a lovely backdrop within the hardware’s limitations.

Todd Marshall was tapped with developing the game’s audio. In his 2014 interview with Scott Stilphen of Ataricompendium.com, Marshall recalled doing a lot of “advanced sound” for Tarzan, and indeed the newly dumped build truly has a unique soundscape. The background drumbeat in particular sounds like nothing else on the 2600 platform and serves as a further testament to the skills of the JWDA staff.

“Well, there were two major challenges (we faced when developing games). One was getting animation that was interesting, dynamic, and fun. Then secondly, getting it all to fit within the memory spaces that are allocated. There is the third, of course, which is not technical, and that’s schedule. Everybody wanted it done yesterday in time for, say, the Christmas marketplace.” – James Wickstead, interview with Kevin Bunch, Nov. 16, 2021

Marshall snagged Will’s development notebooks when JWDA closed up its video game business, which have since been made available online through the scanning efforts of Scott Stilphen. This document contains a great deal of details about Tarzan’s development, including that it initially got underway in October 1982 with Sylvia Day leading, though the idea for a Tarzan-based game was initially pitched in January. Work on this initial, 4-kilobyte version was halted December 2nd for about 8 months – according to Will, this was because Warner was producing Greystoke and they expected Atari, a subsidiary of Warner, would be getting the home game rights. During that break he was moved over to working on other projects, such as Smurfs, while Day and Booth were shuffled over to the similarly unreleased Pursuit of the Pink Panther. JWDA received the green light in August to return to Tarzan, now using an 8-kilobyte cartridge (later expanded again to 12 kilobytes in September, with the newly available game coming in at 16 kilobytes). Will no longer recalled where the unique bankswitching scheme used in the prototype came from, but considered it likely to have been developed by JWDA’s hardware engineers, the late Tom Heidt and Jerry Sullivan. Additionally, Marshall recalled in his interview with Stilphen that Tarzan was supposed to use a custom combined RAM/ROM chip (used in Pink Panther) that would include additional memory on the cartridge, but Will’s notebook doesn’t suggest that this was used in Tarzan, nor does the final prototype utilize it.

Taterczynski provided his feedback to JWDA several times over the course of its development in the fall through early 1984, remarking for an early build from September 1983 that he thought “Tarzan in general is great – better than Jungle Harry in Activision(‘s Pitfall!).”

Based on Will’s notebook, the final version of the game appears to have gone to Coleco on or around April 30, 1984, following months of revisions and requests by the publisher and the Burroughs estate. These ranged from enlarging the game’s sprites to reducing Tarzan’s movement speed and capabilities to make the game more challenging, but Will recalled the working relationship with Coleco was quite positive.

“I’m sure there were times when I had to push back (against Coleco’s notes), but usually, it’s because of a technical limitation or something. Or it might be gameplay feedback or whatever, and we talked through that, but I don’t remember (Taterczynski or Coleco) really getting contentious. – Henry Will IV, interview with AtariSpot, July 8, 2023

The Game Itself

Tarzan is a remarkably robust game in this seemingly final build. According to the scanned manual, you control the titular character on a quest to save his ape friends from hunters and the Beastmen of Opar, who have captured them. Tarzan can run, swim, climb, leap, and punch on his road to rescue, and which actions he’ll need to take vary from screen to screen. If a screen features a hunter or Bolgani, a hostile gorilla, Tarzan has to avoid their attacks and get past them, punching them to stun them if necessary. Histah the viper also shows up on some screens and can only be stunned by jumping or falling on top of it. Few fights in this game are required, however, as Tarzan can usually simply run past them, or even climb the trees and leap from trunk to trunk (or trunk to vine, as the case may be). Watery sections will feature a crocodile called Gimla that Tarzan simply has to avoid, either by swimming and leaping around it or by taking to the trees.

There are special screens Tarzan can’t simply dash through. The hunter encampments are denoted by a cage with gorillas atop a post in the center of the screen that Tarzan must reach and punch open while avoiding gunfire from a hunter. Other screens feature multiple cages protected by a Beastman Tarzan must punch out; only then will his ape friends escape. Eventually, Tarzan will also reach a cliffside, which he must scale vertically while avoiding falling rocks. There are black lines denoting ledges that he can hide under, a real blessing since the rocks seemingly fall randomly. Further on Tarzan will reach the Temple of Opar, where more apes are imprisoned and freed by Tarzan punching open their cages. The final screen of the game is another cliffside, where the Beastmen are attempting to lower caged apes down to the hunters using a chain. Tarzan needs to leap over to the chain, punch open the cages, and then leap back to the cliffside before they shake him loose. Once all the apes are freed, the game tallies up your remaining time for a score, and begins another loop. If you run out of time before saving all the apes, the game ends rather abruptly.

Each of the game’s four difficulty levels adds more screens you need to make it through before reaching the final cliffside, making it increasingly harder to finish without running out of time. Additionally, time ticks down three times normal speed whenever Tarzan is stunned, making it imperative to keep him healthy and upright as you work through the game. And seemingly in recognition of just how long this game can be, the Select switch on the 2600 console is used as a pause feature, with the game unpausing after the controller is moved.

Tarzan’s 2600 outing plays quite closely to the released ColecoVision version. It’s missing some elements, such as traps on the ground, additional attacking elements on the temple stage, and decidedly more aggressive enemies; it also certainly doesn’t have the visual panache of its counterpart. Despite this, it is a remarkable achievement on Atari’s creaky, 1977-era hardware, and is in some regards a friendlier game to play through. The game world is large even on the lowest difficulty, the game’s pacing and varied challenges keeps things interesting, and that steady musical beat is surprisingly engaging. Tarzan’s quality speaks highly to the game design sensibilities American developers had in 1983 and 1984, years that commonly and unfairly get lambasted as an era of bad games and lazy cash-ins. Unfortunately, the games being developed in this era found themselves in a difficult market, if they came out at all.

The Crash, Atari, Coleco, and the Wreckage Left Behind

By the point Tarzan was completed and delivered to Coleco, the bottom had fallen out of the home video game market in North America. Historian Alex Smith has noted that Atari’s own product tracking system and inability to ship the requested amounts of product to retailers and distributors in 1980-1982 ended up imploding the market when retailers started ordering more than they wanted to account for these short orders, and actually received the full amount. As the largest player in the video game space, this created a knock-on effect where there were simply too many games on shelves for consumer demand, dragging other companies into the morass and creating a race to the bottom with cartridge prices. While this was a great situation for consumers, who could and did buy whole libraries for a couple dozen dollars, it was disastrous for retailers, distributors, and the people developing and publishing the games.

Coleco’s final 2600 release, a home conversion of the Konami arcade game Roc ‘N’ Rope, came out in June 1984, and evidently at that point Coleco no longer considered it cost-effective to release new games on the platform. Schick remembered receiving the finished 2600 game, but had forgotten it hadn’t been released, speculating further that if the cartridge required special hardware to run, that would have made it more expensive to produce and likely not financially viable. Will wrote in his notebook about the state of the industry looking on the whole rather bleak at the winter 1985 CES show, where Tarzan was a no-show despite months of work and a finished product.

“The reason I wrote that (comment in my notebook) there is because I was really disappointed, you know? I guess they have to make the decisions they have to make, but after you put that much time into something, it’s like your baby. So yeah, I was disappointed that it didn’t come out.” – Henry Will IV, interview with AtariSpot, July 8, 2023

This isn’t too surprising – in July 1984, parent company Warner Communications spun off Atari’s consumer business to the former CEO of Commodore, Jack Tramiel, including all its assets and liabilities. While Tramiel declared he was still committed to the 2600 and even started producing new units (seemingly for overseas markets) the company itself wasn’t selling any *new* games for its mainstay console until 1986, when the market crash had finally subsided. Parker Brothers, Activision, and Sega were the only major publishers left on the platform in that interim period, and even they had largely ceased by the end of 1984.

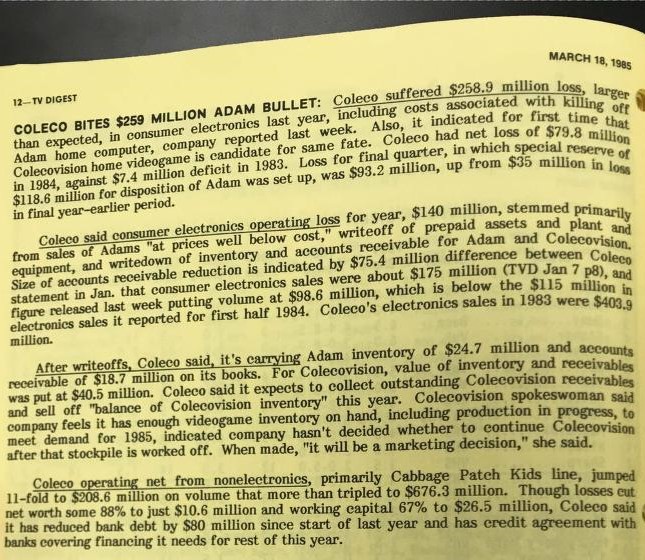

Concurrent to the game market’s troubles, Coleco introduced its ADAM computer in the fall of 1983, which, in addition to technical problems, led to it being caught up in the ongoing computer price wars between Commodore and Texas Instruments that decimated the consumer computer market. Coleco finally dropped support for the ADAM in January 1985, reporting losses of $140 million for Fiscal Year 1984 primarily because of needing to sell the computer below cost to compete.

Coleco continued supporting the ColecoVision platform itself through this difficult period, with some of the console’s most ambitious games appearing in this period, including its own version of Tarzan, Illusions (developed by Nice Ideas, formerly Mattel Electronics’ French development house), and 2010: The Graphic Action Game. Coleco quietly discontinued the ColecoVision in the summer of 1985 and sold off its remaining inventory to liquidators, mere months before Nintendo’s test market of the NES took place in New York.

“I was pretty pleased with CV Tarzan, as I recall, the final version fulfilled most of my original design goals. I thought it played well and looked and sounded good.” – Lawrence Schick, correspondence with Kevin Bunch, Feb. 18, 2024

Schick left Coleco in 1984 having learned all he could from the experience, according to an interview published in Coleco – the Official Book. Jaquays, who remained at the company longer, remarked in an interview published in the same book that roughly 70 people in the art, engineering and design department were laid off on Jan. 2, 1985, with additional attrition taking place over the ensuing months before she was laid off with the rest of her staff in June.

As for JWDA, Will’s development notebooks paint a pretty rough picture overall for staff in late 1984. Will wrote on August 22 that major client Parker Bros had just laid off the vast majority of its video game department and had negative royalties for JWDA. In retrospect, he remembered some rough moments where royalty checks dried up and the regular paychecks were delayed, as Wickstead was paying everyone out of pocket, though similarly Will remembered Wickstead doing his best to keep everyone up-to-date on projects they were pitching or receiving. JWDA left the video game market behind around 1985. Wickstead said the company continued on developing products, such as the Etch-a-Sketch Animator published by Ohio Art and the Pixel 2000 for Fisher-Price.

“It was one of those marketplaces that you look at with interest to get involved in, and then you look back on it after a little time (has passed), and you think, ‘Well that was fascinating. God, how did we ever survive that?’” – James Wickstead, interview with Kevin Bunch, Nov. 16, 2021

The North American Crash, the Atari Shock, or whatever else you want to call it, was an incredibly traumatic event for game development in the US. Most of the companies that had been making games just years prior closed their doors, laying off hundreds or thousands of people in the process. These were designers, programmers, artists, marketers, assembly workers, and more who found themselves out of work and trying to pick up the pieces. Some were able to pivot to the home computer space, find work at the surviving developers and publishers, or form new game companies. Others left video games behind entirely. In many of these cases, the projects they were working on were simply and quietly canceled, regardless of how close they were to completion, never intended to be seen again – just a failed product that didn’t make it to market. Like Tarzan.

In the years since, a number of these canceled games have been discovered, saved on cartridges for beta testing or for reviewers, or even on development disks, tapes and drives. Each of these finds is a minor miracle, that copies of a game that may number in only the low single digits survived time, entropy and life to find its way to someone able and willing to recognize it as a feat of human ingenuity, training and thoughtfulness. Even design materials or coverage for games that haven’t surfaced can provide a glimpse into an alternate future, where American game designers didn’t suffer from a series of failures that one major company made and that their hundreds of hours of hard work were recognized by players and their peers. In the case of Tarzan, it may have taken 40 years, but today, this herculean effort by Jaquays, Schick, Taterczynski, Will, Day, Marshall and McDaniel Ballweg can be recognized as the would-have-been VCS masterpiece that it is, and an absolutely stellar capstone to JWDA’s 2600 library.

As of this writing, the games industry is going through another convulsion. Despite a massive number of acclaimed releases in recent years, thousands are being laid off. Much like industry staff in 1983 and 1984, there will be projects they worked on that go unfinished or unpublished, and some will be unable or unwilling to continue working in the games field, delivering a blow that will reverberate for years, much as the aftermath of Crash did. Organizations like the Video Game History Foundation didn’t exist 40 years ago, but thanks to it being here today, these folks have an opportunity for some of their materials to find a home where an appreciative audience can explore it in the future to understand what had come before – just as materials like Will’s notebooks and Tarzan itself do for our understanding of JWDA and the Crash.

Thanks to owner AtariSpot for ensuring Tarzan was successfully dumped and made available, and to Thomas Jentzsch for the F6 bankswitching conversion. You can find both the original ROM file and a modified one that can run on emulators and flash carts on Archive.org.

Correction 6-6-2024: The article has been updated to note who scanned Henry Will’s notebooks and to reflect new findings that Tarzan’s ROM is not 12 kilobytes (with one bank doubled) but rather encompasses the full 16 kilobytes of the bankswitching scheme used.

About the Historian

Kevin Bunch is the author of Atari Archive Vol 1: 1977-1978, a book now available through Amazon and Limited Run Games detailing the Atari VCS/2600 game console, its competitors and the market it first existed in. He also produces videos on the companion Atari Archive YouTube channel, a Patreon supported endeavor. He can also be found occasionally guest-hosting the Retronauts podcast.

Special Thanks to AtariSpot, Henry Will IV, James Wickstead, Lawrence Schick, David Craddock, David Wolinsky, Scott Stilphen, Todd Marshall, Tim Duarte, Jennell Jaquays, Thomas Jentzsch, and the Video Game History Foundation’s staff.