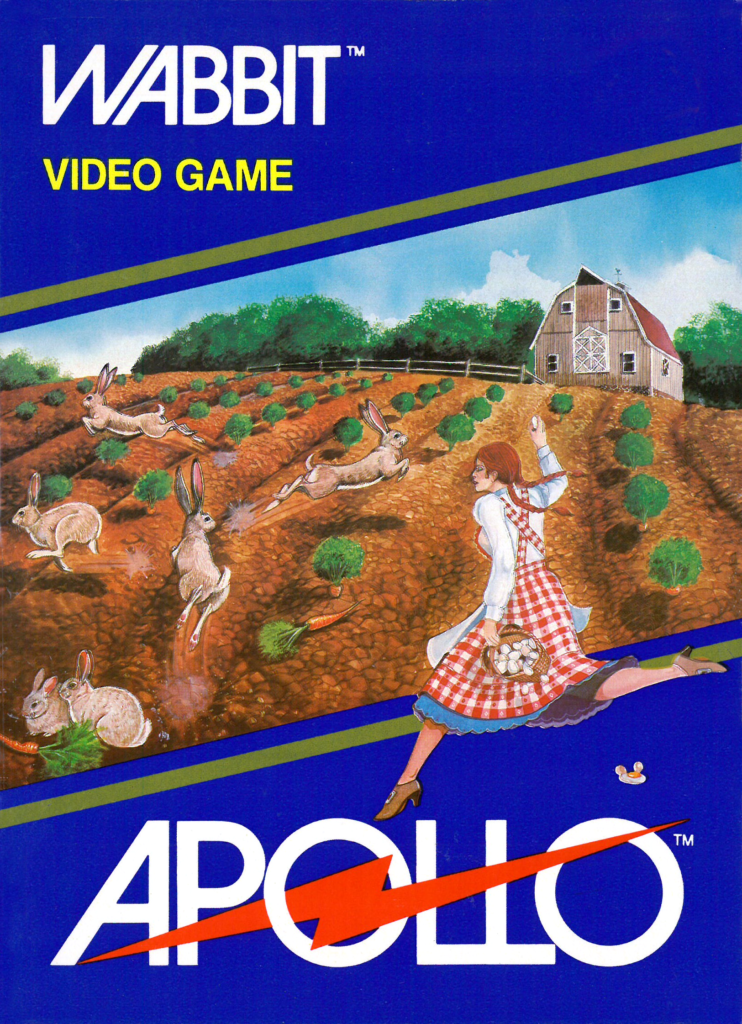

Last year, Polygon ran an article about our search for an Atari VCS game developer by the name of “Ban Tran.” As we understood it, Tran was a Vietnamese woman who worked for a short-lived, Texas-based game company called Apollo, where she wrote Wabbit — the first console game to star a human girl — before the company declared bankruptcy towards the end of 1982.

However, after working on an unreleased Solar Fox conversion the following year for the Atari 5200 at MicroGraphic Image, Tran simply disappeared. And while there are many people in the United States by that name, none of them appeared to be her. The article on Polygon concluded with musings that her old coworkers may have simply mis-remembered her name.

As it turned out, they were only one letter off.

Finding Van Tran

Van Tran was found with the help of collaborators at the Video Game History Foundation, which responded to the article by starting up a channel in its official Discord dedicated to tracking her down.

The big breakthrough came from member SoH, who had the idea of contacting the National Archives down in Texas to look through their bankruptcy records. Several of Apollo’s employees had to go through the court to get final royalty checks for their games, and as it turned out, Tran was one of them. Armed with this new information, we were able to finally reach out to her (now going by a married name, Van Mai), and she graciously agreed to an interview to tell her story.

Mai was born in Vietnam. As a teenager, she entered the US as a refugee at the end of the Vietnam War, settling in with her family in Dallas. After dropping out of high school due to the language barrier (she later got a GED), she said a friend of hers suggested they take night classes to learn how to operate and program computers. She didn’t know much about computers going into those classes, but found she liked working with them, even if the school’s IBM 370 meant her first forays into programming were done using punch cards.

Upon getting her certification, Mai was hired as a programmer at the Dallas Independent School District. The district had a team developing lesson plans as part of a computer-based curriculum, and Mai’s job was to program these lessons in BASIC for the district’s TRS-80 computers. The work was simple, but introduced her to working on computer graphics and animation, which she enjoyed.

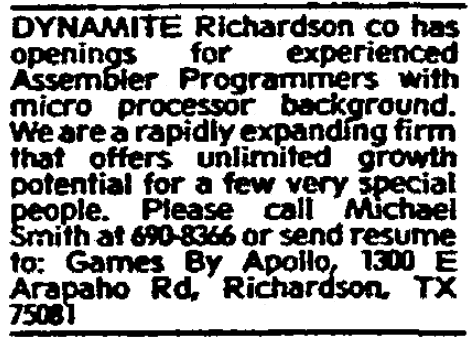

Eventually the district cut the computer lessons program, and Mai was back to looking for a new job. She just happened to spot a Help Wanted ad Apollo had printed in the newspaper looking for programmers to work on video games. Since her family lived near the Apollo offices at the time, she figured it was worth checking out.

Joining Apollo

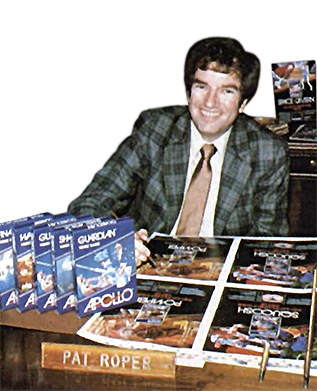

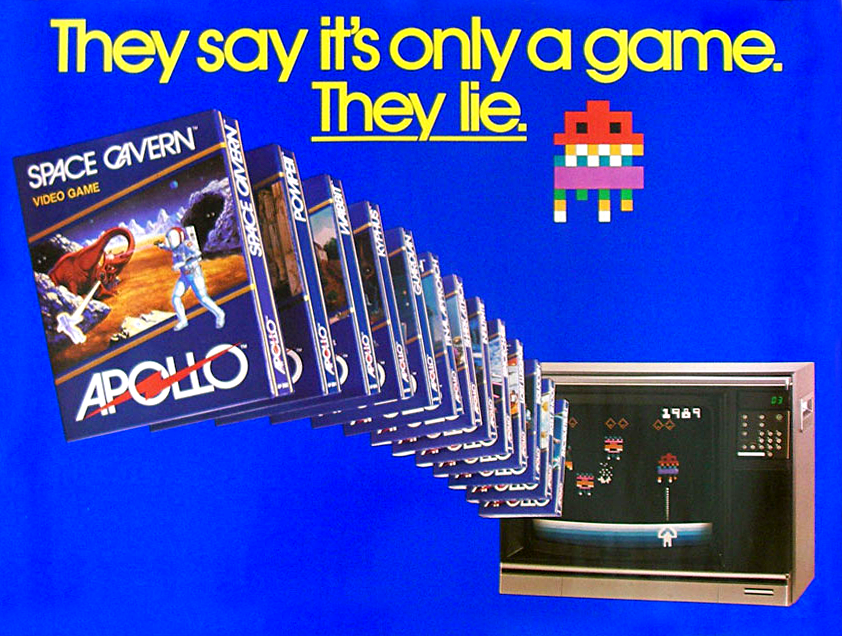

Games By Apollo (rebranded in 1982 as simply Apollo) was founded by Pat Roper in 1981 as a subsidiary of National Career Consultants (NCC), with his sister Judith Burnett joining the company soon after to help out. While Roper passed away in an auto accident in the 1990s, contemporary magazine interviews – as well as correspondence with his sister – paints a clear picture of Apollo’s history.

According to Burnett and interviews with Roper in the August 1982 Videogaming Illustrated and the January 1983 edition of Electronic Fun with Computers and Games, NCC originally produced educational film strips before a California “Back to Basics” law started hurting their business. Roper had a habit of taking the company’s petty cash to play video games, and after a round of NFL Football on the Intellivision, hit on the idea of saving NCC by making home video games themselves.

Roper put an ad in the October 17 editions of the Dallas Morning News and the San Francisco Chronicle seeking a programmer who knew assembly. He found Ed Salvo, an Oklahoman who had learned how to program Atari VCS games using the MagiCard, a programming cartridge produced by Computer Magic earlier that year. Salvo sold Apollo a target shooting game named Skeet Shoot, which hit stores in December and kicked off a rapid series of releases and growth through 1982.

At its peak, Apollo employed 50 people, including 15 programmers, and with its own production facility attached to the main office building Apollo was able to turn around software cartridges quickly.

Mai’s coworker at Apollo, Dan Oliver, recalled that she was interviewed for the job by Salvo, who was the head of software development by this time. At first glance she didn’t strike Oliver as the kind of “nerd” they expected to be applying for a job at Apollo, but she quickly set herself apart from the other interviewees by coming up with a game concept during the interview.

“It was an extremely-intense concept and made Night Trap look like a bedtime story for kids, but it was 20 years ahead of its time and way too intense for the VCS,” Oliver remembered. “She was explaining it like it was a picnic at the beach, so pretty quickly the stereotype started to fall.”

Mai herself doesn’t remember what this concept may have been, but she does distinctly remember during a team meeting pitching her managers on an Atari game for little girls, which would become Wabbit. In it, a little girl named Billie Sue shoos away rabbits that are trying to steal her vegetables.

“I don’t think my teammates or my boss said anything about [the theme],” Mai said. “Everything was up to me, I designed it – all the animation and all that. They seemed to like it a lot.”

Programming Wabbit

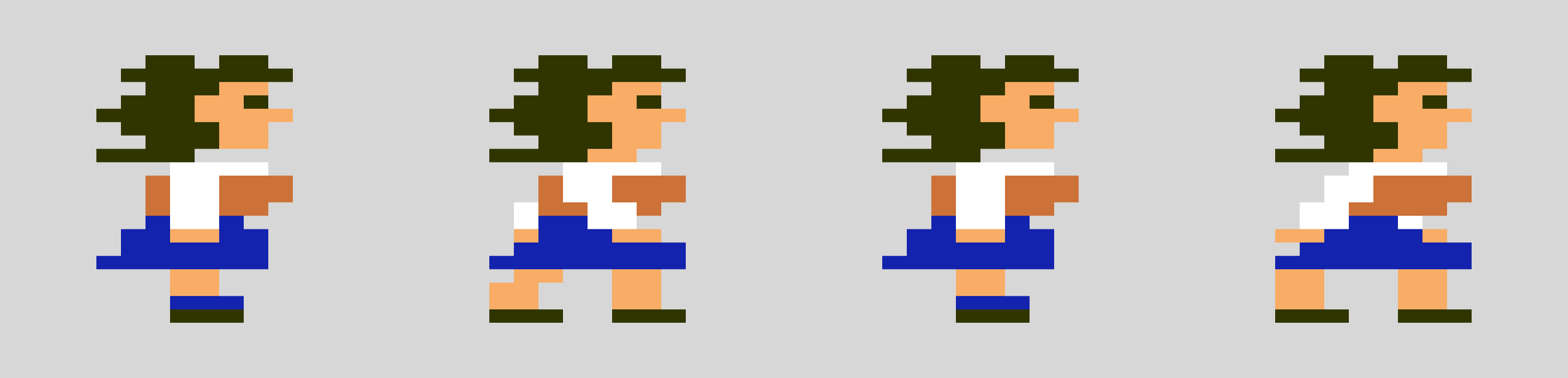

Mai’s background in computer graphics and animation paid off with Wabbit, which features relatively intricate detail given the limitations of the Atari VCS platform and the 4k cartridge she had to work with. While it starts off slowly, eventually the rabbits begin moving in so quickly that the player needs to essentially predict their movements in order to protect the garden.

Instead of a life count, the game uses an innovative score-based survival mechanic, where the game only ends if the rabbits score 100 points; but if the player scores a multiple of 100, the rabbits’ score will dramatically drop and buy the player more time.

“I was very proud of myself,” Mai said. “Within the limitations (of the VCS), RAM and everything, and the (cartridge) space, I could put one game into 4k like that.”

With only four kilobytes of cartridge space, Wabbit had to have some trade-offs. Mai said she originally included a flashing sunbeam graphic, but it had to be cut to make room for the game audio and the game over tune that plays when the rabbits finally win. Nevertheless, she appreciates the lessons she learned from the experience.

“It taught me how to write compact code, to write good code,” Mai said. “Later on, when I went to university, they didn’t care much about RAM or computer space, they had plenty. I think I’m a pretty good coder because of that, because in the beginning, there wasn’t much room to write your logic, and you have to write good logic because of space.”

The sprite for the player character, Billie Sue, is notable for being particularly colorful on a system where sprite objects were intended to be a single color that could be turned on (visible) or off (allowing the background color to show instead). But because the VCS draws the screen one scanline at a time, it’s possible to change colors line-by-line, which was used here. She also overlaid two different player sprites to create Billie Sue — one sprite covers her hair, eye, dress, and shoes, while the other handles her skin tones, the soles of her shoes, and the white parts of her outfit. A similar technique was commonly used in NES games.

“I think the reason why I put more color in her was that because of the animation,” Mai said. “If you looked at her walking sideways, she moves her arms like (she’s) normal walking. And I think the reason why I put white color in the shoulder portion of her shirt was so that it will distinguish her arm’s movement against her red/orange shirt. I remember I put no color, or the background color, to draw the pixels to show her arm, but it did not show up very well … And a different color for her hand or the skin color.”

At Apollo, she said programmers were largely broken out into smaller teams; while everyone was responsible for their own individual game, teammates would frequently give each other feedback. In her case, her team consisted of herself, Larry Martin (who wrote Guardian, the last game published under the Apollo name), as well as someone formerly involved in the airline industry whose name she couldn’t recall. Mai said she and Larry made a pretty good team, regularly going out for lunch together and brainstorming about their respective games.

In all, development on Wabbit took about 4-6 months, she recalls. The game was showcased at the Texas State Fair in October before reaching stores shortly afterwards. Mai had no insight into how successful the game was from her end, but she remembers her nieces tried to buy a copy at a nearby mall only to be told that it was sold out.

“My mom was proud of me,” she said.

After Apollo

After finishing Wabbit, Mai started on a new game but didn’t get very far before Apollo filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on November 12. It would never reemerge. Mai said she was paid a salary at Apollo, but in the last few months the programmers got the company to agree to also pay them royalties on copies of their games that were sold. After the bankruptcy, her royalty check ended up taking nearly seven years to arrive.

With Apollo gone, Mai was back to looking for work, though this didn’t last long. Three of her former Apollo colleagues – Tim Martin, Cash Foley, and Robert Barber – formed a video game development company called MicroGraphic Image, using money that Martin and Barber had earned working on a VCS Halloween game that was contracted out to them by VSS, a company founded by Ed Salvo with several other former Apollo managers.

Mai thought Ed Salvo might’ve been the one who interviewed her for MicroGraphic Image, but wasn’t positive. Whoever it was, he told her that when he saw she was applying, he said, “I don’t need to interview her, I already know what she can do!”

The working environment at MicroGraphic Image was a bit different from Apollo’s, with Mai recalling that the founders would argue amongst each other regularly. But it didn’t interfere with her assignment, which was to write an Atari 5200 conversion of the arcade game Solar Fox as a contract job for CBS Electronics. Solar Fox was showcased at the 1983 Summer Consumer Electronics Show, where it reportedly impressed show-goers for being nearly arcade-perfect; but while it was advertised for an October release, the game never came out. As of this writing, a copy of the game has not surfaced.

“They brought in the arcade (machine) so we could convert it to a home game,” Mai recalled. “We could not write the whole game like the arcade, but we could write a simpler version on the smaller Atari 5200.”

Mai said she worked on the Solar Fox conversion for about “five or six months” before departing Micrographic Image. The game was far along but not yet completed by the time she left, and she had no information on who may have taken over the job once she left the company. Rather than stick with video games, Mai instead moved to California, where she earned a degree in computer science. After a few years there, she moved back to Texas and found work as an Oracle developer for a French telecommunications company. Today, she works in the banking industry.

While her time in video game development is well behind her by this point, Mai said that she has thought about returning to the field, though she believes her time away from computer programming and the array of new tools poses a hurdle. But she said she has very fond memories of her time at Apollo.

“It was wonderful,” Mai said. “Writing games is the most — I don’t know, I can never find a job like that. You just go in there and play games for a while to get ideas, and then sit around and talk to your teammates, just giving each other opinions. It was fun.”

About The Historians

Kevin Bunch is the host of the Youtube series Atari Archive, which looks at the history of the Atari VCS (aka the Atari 2600) one game at a time.

“Critical Kate” Willaert is the host of the Youtube series Video Dames, which looks at the history of playable female protagonists one game at a time.

Special Thanks to Judith Burnett, Frank Cifaldi, Cat DeSpira, SGreenwell, Patricia Hernandez, Ethan Johnson, Kelsey Lewin, Dylan Mansfield, Tim Martin, Lisa Marie Mary, Zach Robinson, Phil Salvador, Jason Scott, SoH, Matthew “Firefang” Stephenson, Rob Wanenchak, and the VGHF community.