In part one we looked at the very first attempt to market a video game. But where that one was targeted at arcade operators, advertising directly to consumers would require a different approach. How do you market a home console to a world that’s never even used a VCR?

This is the story of Odyssey.

Creating The First Home Video Game

In 1966, a designer of military electronics had a revolutionary idea: what if people could interact with their home television set?

Ralph Baer began tinkering with the idea in secret at work, at one point even borrowing a spare technician to help him flesh out a proof-of-concept. When he finally showed his bosses at Sanders Associates what he’d been working on, they naturally fired him on the spot.

I’m kidding. They were impressed and approved the project.

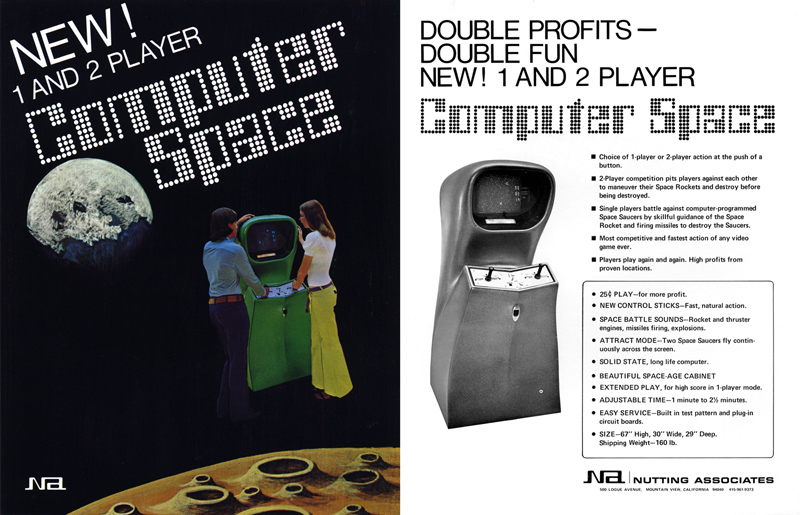

The only problem is that Baer was having trouble coming up with fun game concepts to play on his device. Unlike Nolan Bushnell at Nutting Associates, Baer was completely unaware of computer games like Spacewar!. And besides, Baer was trying to keep it simple. Rather than showcasing a powerful computer, he was trying to develop something that would be affordable at a consumer level.

His initial ideas involved simple actions, like mashing a button to cause a flat color to rise from the bottom and fill the screen. If an overlay of a burning house was placed on the screen, the flat color could represent water that “fills up” holes cut into the overlay.

“Pumping” games continue to show up today as mini-games, but could you imagine playing only variations on that concept over and over?

Ralph Baer recruited an engineer named Bill Rusch for some additional brainstorming sessions, which resulted in a number of concepts that revolved around using controllers to move two dots around on the screen. If a board game overlay was placed on the TV, the two dots could function as game pieces. Or, the dots could chase each other and play tag. These ideas were more promising, but there was still a general concern about replay value.

When Bill Rusch was brought on as an official member of the team, he had an idea that would be a literal game-changer:

What if they added a third dot that wasn’t controlled by either player, that could be hit around by the other two dots, like a game of ping pong?

In 1969, Sanders Associates entered talks with Magnavox to produce a consumer model, the same year Nolan Bushnell discovered Spacewar!. Baer and Bushnell were now in a race to launch the first for-profit video game machine, and neither of them knew it.

Unfortunately for Ralph Baer, negotiations with Magnavox took just a little too long, and Nolan Bushell was able to beat them to market by about a year. But Baer and Magnavox were still the first to bring video games into the home.

Launching The First Home Video Game

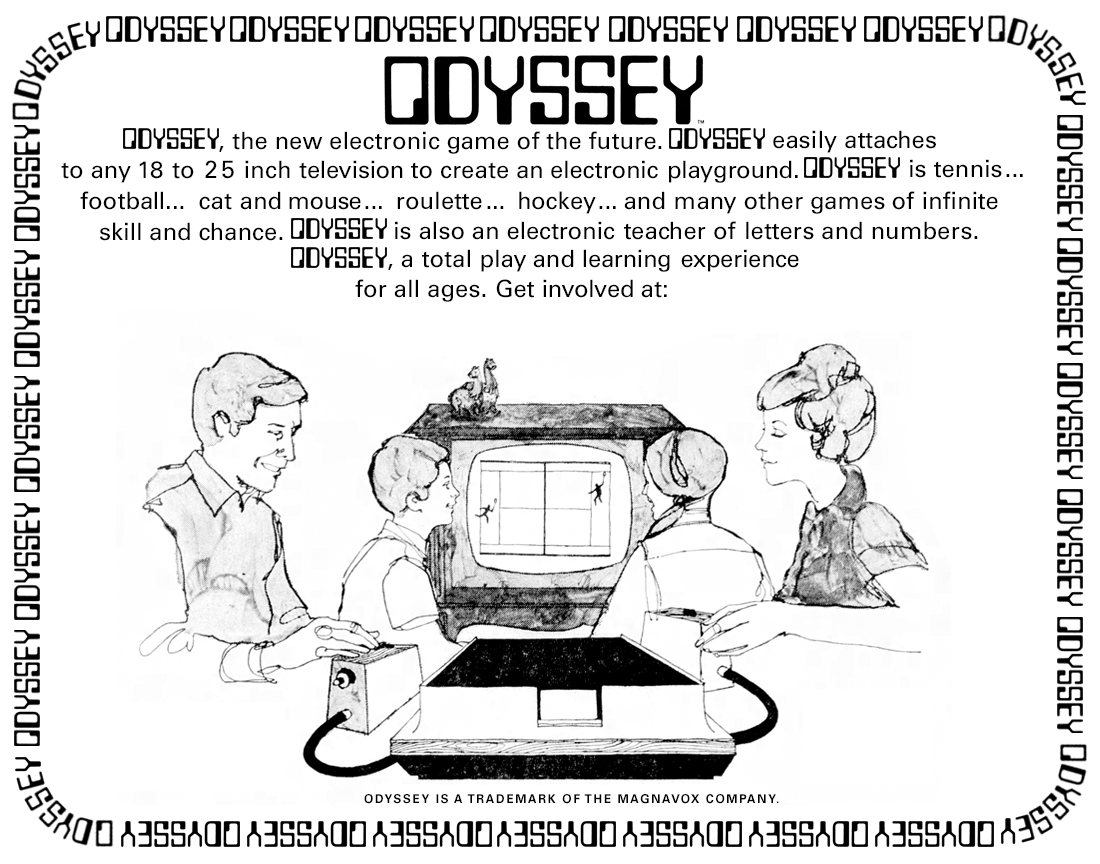

Magnavox launched the finished product in the fall of 1972, naming it Odyssey, perhaps in reference to the recent sci-fi film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Although it’s tempting to call it “The Odyssey” or “Magnavox Odyssey,” marketing materials always called it simply: “Odyssey.”

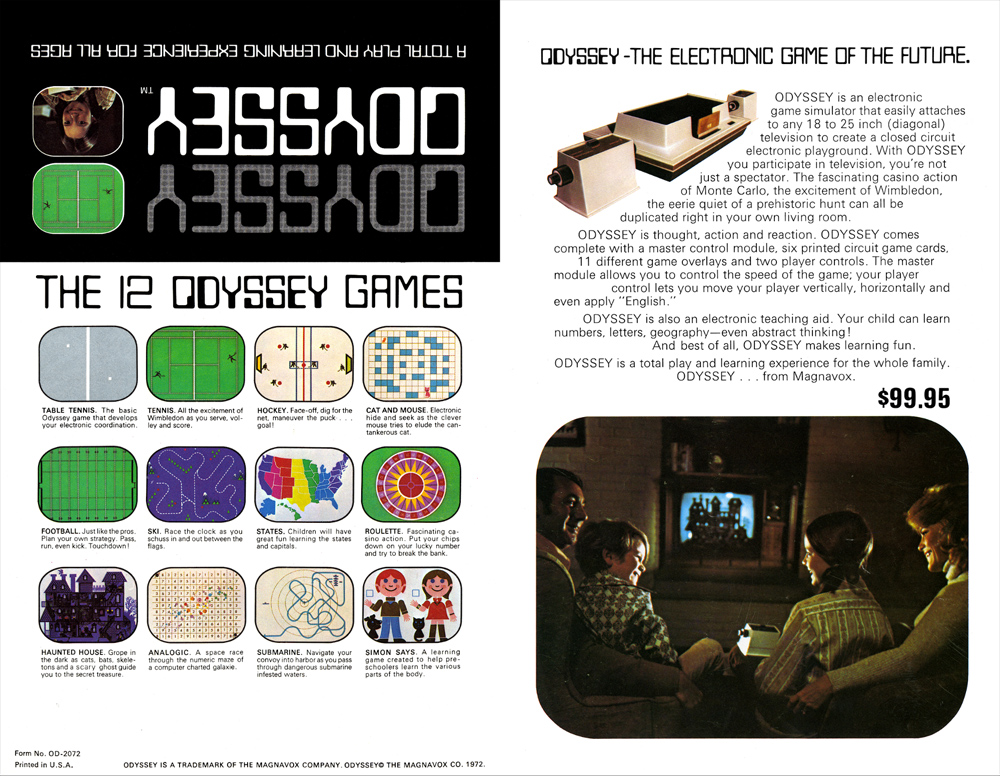

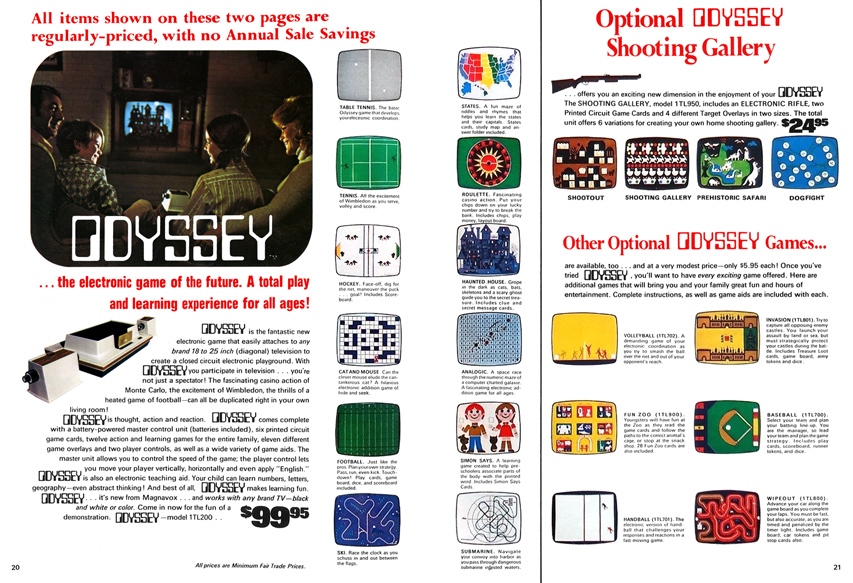

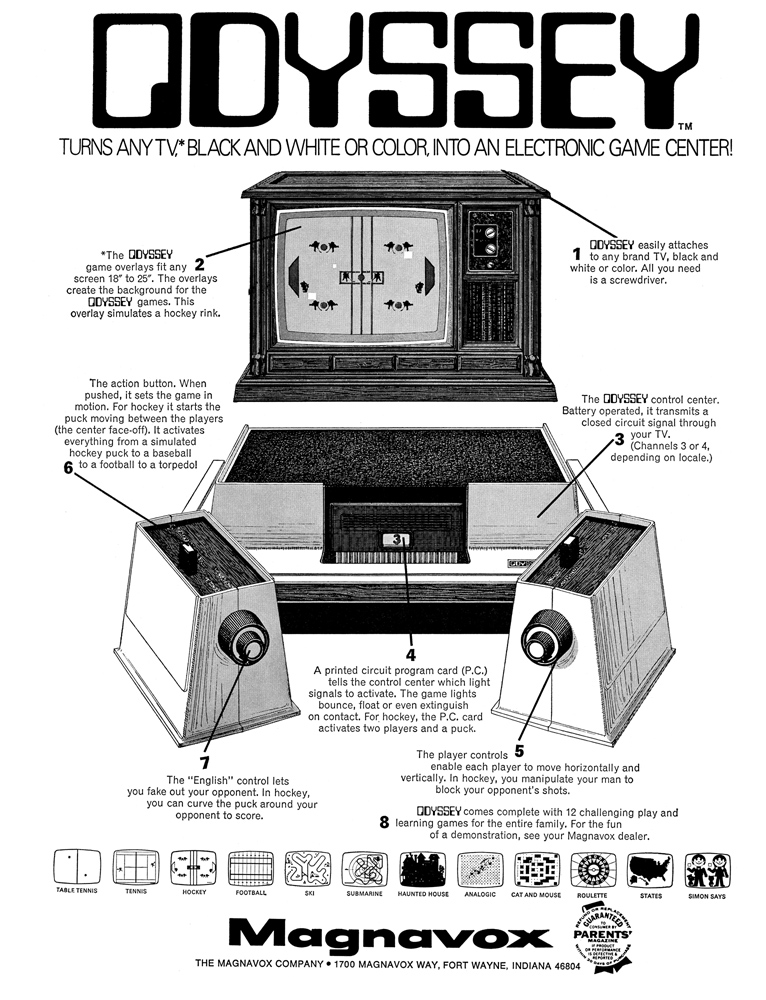

Odyssey came packaged with twelve different game modes, most of which were essentially just board games that used your TV as the board. But the main attraction was clearly ping pong, with the first three game modes being just variations on that, called Table Tennis, Tennis, and Hockey.

But what do you call a video game console when the term “video game” isn’t yet a thing? Magnavox’s first brochure provided a number of options:

- An electronic game simulator

- A closed circuit electronic playground

- A total play and learning experience

- The electronic game of the future

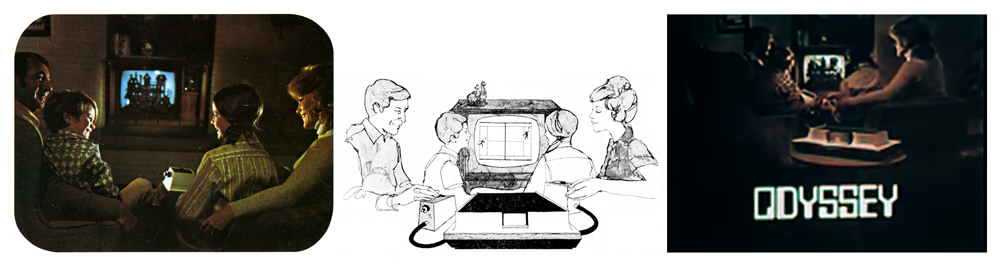

The first brochure was likely printed before the box art was finalized, because most of the screenshots are early prototype versions, similar to the ones that made it into the first commercial.

Some of these prototype images did make it onto the final packaging, such as Tennis, Hockey and Cat And Mouse. But the brochure features additional prototypes, most noticeably Roulette, but also Analogic, and Submarine.

Just how early was the brochure released? Was it available during Magnavox’s touring trade show, where they demonstrated Odyssey the summer before launch?

I suspect it might’ve been, because a second brochure was printed the same year that’s much more in line with the box art.

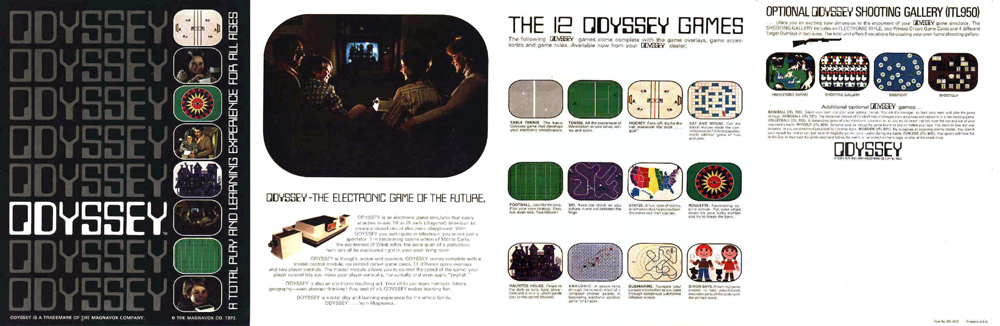

This brochure used updated art for Roulette and Analogic, and added screenshots of the Shooting Gallery games.

Strangely, the title for the “Optional Odyssey Shooting Gallery” doesn’t match the style of the other titles. In the first brochure, the designer did the titles in a custom-made non-bold variation on Odyssey’s logo type.

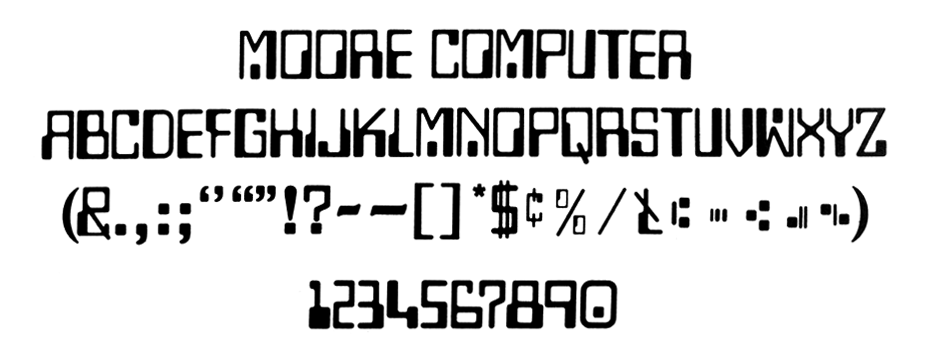

Odyssey’s logo was based on a font called Moore Computer, which we would’ve called a “typeface” back then, but language evolves and now we call them fonts. Live with it.

According to Fonts In Use, Moore Computer was designed in 1968 by James H. Moore, and was later digitized under the name Computer, but good luck searching the internet for “Computer font.”

But who was responsible for the obscure non-bold variation, which has never been digitized? The packaging was created by Bradford/Cout Design, but I’ve analyzed both of their styles and I’m still not positive whether it was Ron Bradford or Al Cout. Bradford definitely designed all the overlays and game pieces, but it’s unclear whether he did the box itself.

The custom-made font was used on all the initial design materials, such as the Odyssey box and the boxes for the first wave of games, and then never appeared again.

Odyssey’s logo, on the other hand, continued to get quite a workout.

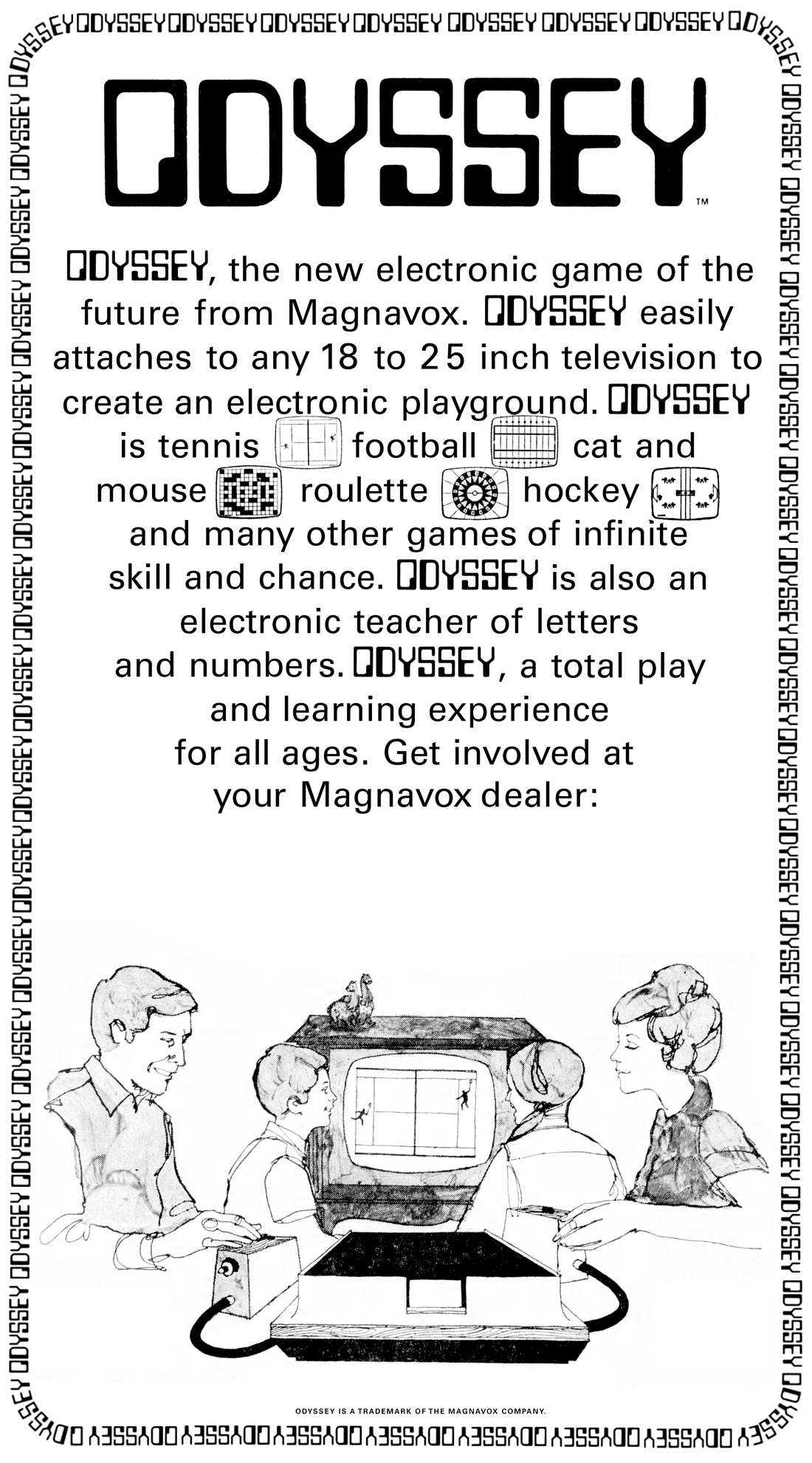

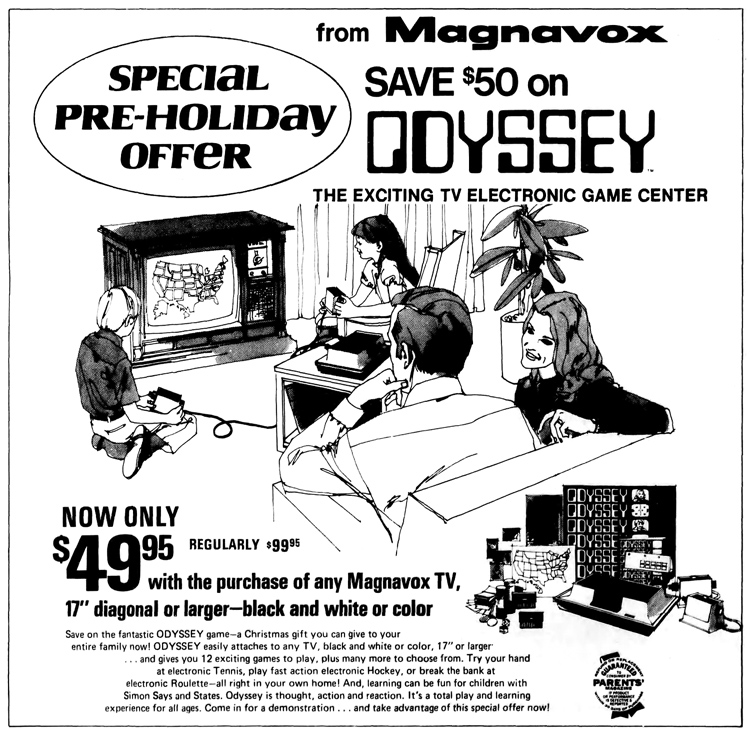

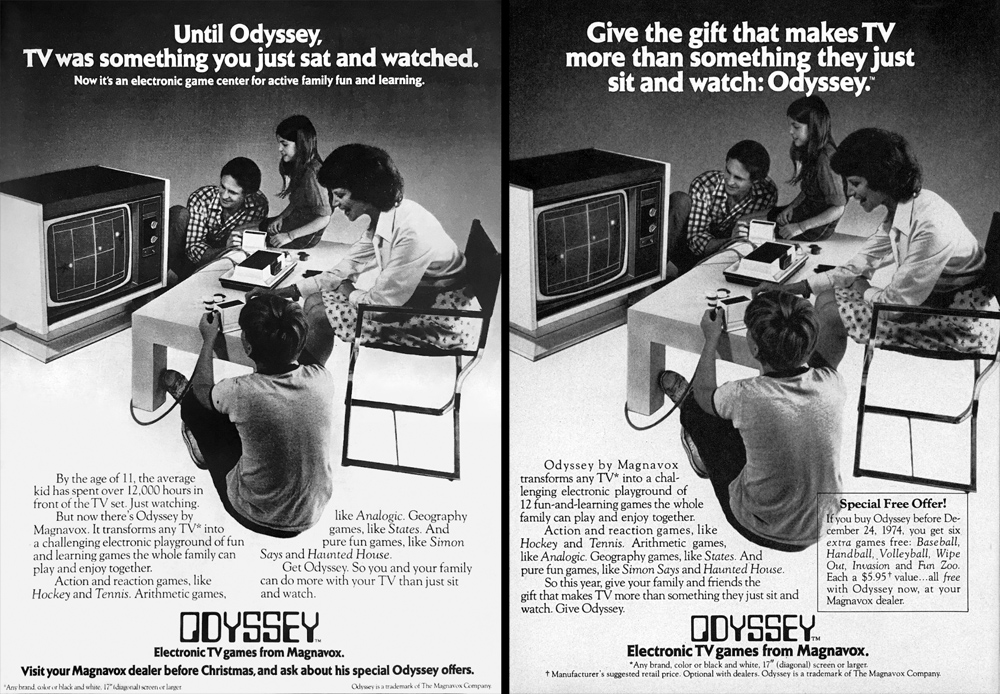

Odyssey newspaper ads came in two basic shapes: short rectangle and tall rectangle. They might not look like much, but these are the first ads ever created for a home video game console.

Or were they the first video game ads, period? Although the ads for Computer Space appeared a year earlier, they were only seen by industry insiders. The Odyssey ads, on the other hand, were the first to be seen by actual consumers.

Either way, the marketing approach between the two couldn’t be any different. Where Computer Space went with “sex sells,” Odyssey is very “fun for the whole family.”

On the other hand, one thing they do share in common is that neither were directly marketing to kids. Just as Nutting was targeting arcade operators, Magnavox was selling to primarily to parents. Hence the focus on Odyssey being educational.

But they also wanted to emphasize that this wasn’t just for kids — it was fun for adults, too!

The illustration looks like it was loosely based on the brochure photo and the shot at the end of the first commercial. Or was it the illustration that came first? Either way, there’s one important difference: in the illustration, the parents are the ones reaching for the controllers. This mirrors the early Odyssey TV commercials which showed the parents playing more than the kids.

And it’s not hard to imagine why Magnavox would take this approach. $100 was a lot of money in 1972 (about $600 in 2019 dollars), and parents might be reluctant to spend so much on a mere toy, even if it was educational. But a fun gadget that adults can enjoy? That’s another story.

The only catch was that you had to live in a city that had a Magnavox dealer, because they were the only ones allowed to sell Odyssey, even though other Magnavox products could be bought at department stores. This exclusivity may be what led some consumers to believe Odyssey was only compatible with Magnavox televisions.

This exclusivity also meant that fewer people at the time even heard of Odyssey, because the ads were only run on a regional basis. Dealers were typically responsible for taking out the ads themselves, with template art supplied by Magnavox.

But the art wasn’t always printed exactly as sent. Since the space reserved for the dealer’s store info was so small, those who didn’t just put their info underneath the ad would sometimes chop it up, or rearrange it to make it fit a different shape.

I feel kind of bad for whoever had to create that border, going to all that pre-computer effort only for someone to potentially throw it away. I hope it was a labor of love and not a directive from above. Repetition can be effective, but it’s called the rule of three, not the rule of thirty, Bob.

Post-Launch 1973

Odyssey’s launch didn’t go quite as planned. Magnavox had projected holiday sales of 50,000 units, and ended up selling 69,000 units. Which is great, right?!

Except an enthusiastic Odyssey advocate in marketing had convinced the company to manufacture more than twice as many units as the projected amount. Now that overstock was taking up warehouse space, making Odyssey look like a flop instead of a runaway success.

But dealers were consistently selling through their orders and wanted more. This must’ve given Magnavox just enough confidence to not discount Odyssey during their big Annual Sale.

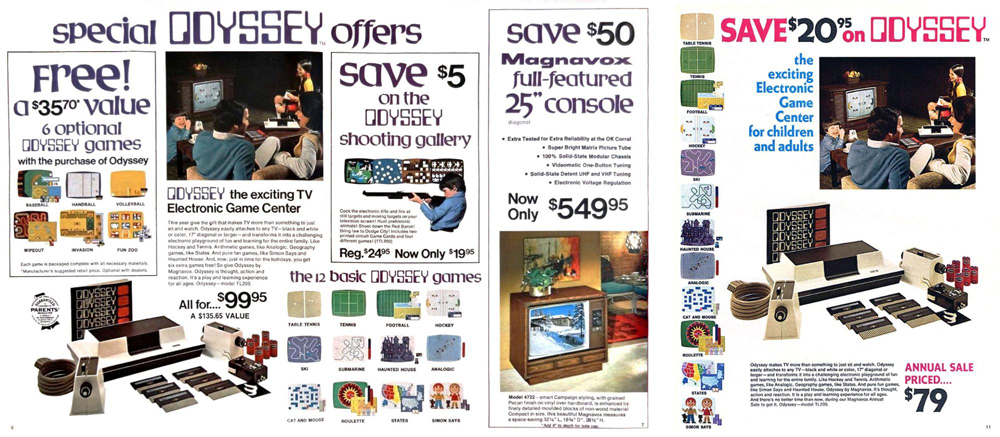

The first catalog ad for a video game was this double-page spread in the Annual Sale catalog for January 1973.

Every year, Magnavox put together two big catalogs: a pre-holiday catalog in the fall, and the Annual Sale catalog in January. These were available in-store in glossy form, but were also sometimes printed on lower-quality paper as a newspaper insert.

Why did Odyssey first appear in the Annual Sale catalog rather than the Fall 1972 catalog? Magnavox was limiting how many dealers would even get shipments of Odyssey that season, so that’s probably why. But I imagine with all that warehouse backstock post-Christmas, they must’ve opened the floodgates right away in January.

My favorite thing about this spread that it reminds me of video game catalog spreads from the ‘80s and ‘90s. Back then, Sears and JCPenney would fill pages with rows of screenshots instead of box art. I never imagined the trend started way back in 1973, but it makes sense. What better way to quickly get across that Odyssey played a wide variety of games?

But one thing that bugs me is that the logo is wrong. It’s so subtle you probably didn’t even notice, but take a look at the uppercase “O.”

In the official logo, the thick portion of the “O” was lowered to line up with the thick portion of the “S.” But somehow, the original “O” snuck in!

And it’s not just once. Odyssey’s logo appears thirteen times, and the wrong “O” is used every time. Did the catalog designer not have the logo on hand, and decided it’d be faster to just typeset it from scratch?

Christmas 1973

Odyssey had a strong Christmas in 1973. Not only did they sell through all that warehouse stock, they also manufactured 27,000 additional units, for a total of 89,000 units sold — better than the previous year!

But Magnavox itself wasn’t doing so well. They began 1973 with a disappointing earnings report just as the stock exchange was entering one of the ten worst bear markets in history. Magnavox stock that was as high as $39 in mid-1972 was already down to $17 by February 1973.

That same month, Magnavox brought in Alfred Di Scipio as their new President of the Consumer Electronics Group at Magnavox, who immediately proceeded to shake things up. One of his big marketing initiatives was a Magnavox-sponsored Sinatra TV special for Fall 1973 that showcased a variety of Magnavox products, including Odyssey.

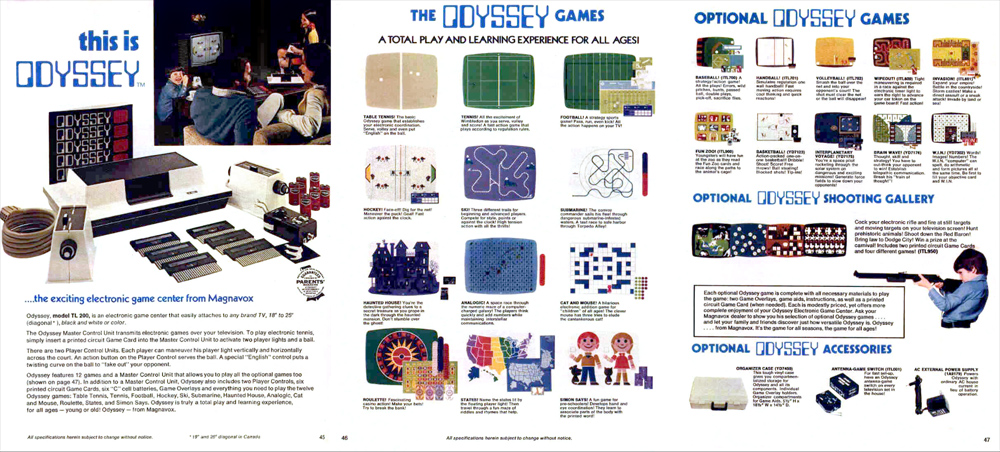

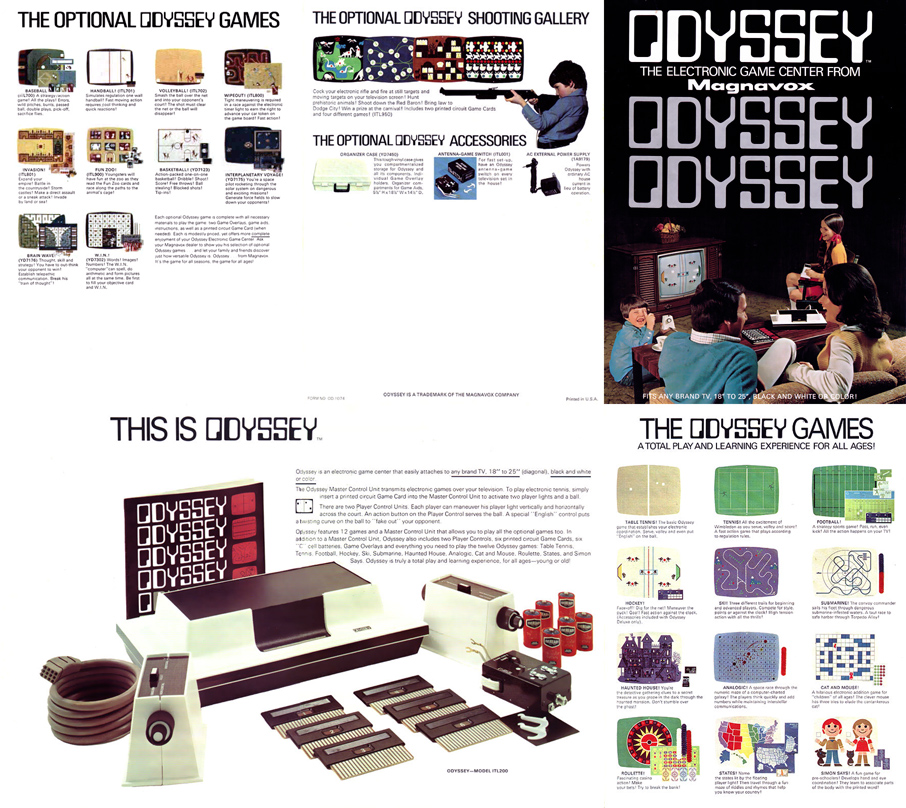

Fall 1973 also saw a makeover to Odyssey’s print assets. This included a new, less-spooky family photo, and a new product descriptor: no longer merely an “electronic game,” Odyssey was an entire “electronic game center.”

Odyssey took up three pages in the Fall 1973 catalog, with a spread that showed literally everything. The four new optional games, bringing to total to ten. The optional carrying case. Even the AC power supply!

And that’s not all; they also displayed all the little game pieces next to their corresponding overlays, to make it extra clear what you were getting.

Afterwards, a revised brochure was released that contained most of the same information. The images were larger, of course. But there’s also a small addition so subtle you might not notice.

In the big block of text under the words “This Is Odyssey,” there’s a tiny little illustration of a ball-and-paddle game trying to draw your attention to the sentence about “electronic tennis.”

Ball-and-paddle games were heating up at the arcades, so it made sense to call that out. But at the same time, why so subtle?

The Fall makeover extended into the newspaper ads, with a new family illustration loosely based on the new family photo. Strangely, the illustration replaced Hockey with States. Did they feel newspaper readers would be more engaged by the educational angle?

I’m not sure why the half-off deal featured here wasn’t mentioned in the catalog ad, unless not all dealers were participating in the deal? But one one small item that did appear in both ads was the Parents Magazine Guaranteed Seal. It’s that little graphic in the lower right corner.

The Guaranteed Seal indicated that Parents Magazine had personally tested the product and were so confident in its quality that they were willing to offer 30 day return policy.

The Guaranteed Seal was inspired by Good Housekeeping’s Seal Of Approval, possibly the most recognizable trust symbol of the 20th century, and likely a direct ancestor to Nintendo’s Seal Of Quality.

The Seal of Approval was originally established in 1909 to help combat unsafe products. Before a product could be advertised in Good Housekeeping, it had to be tested in-house. As a bonus, any product that passed the test could include the seal on ads outside of the magazine.

Parents Magazine worked the same way, which meant Magnavox took out a magazine ad. And here it is:

The first full-page magazine ad for a home video game.

I’d say it was a pretty bold move advertising in a national publication when the product was only available in cities with Magnavox dealers, but the Sinatra special was far more bold. Magnavox hoped that the uniqueness of the product would convince people to seek out their nearest Magnavox dealer.

I love that the first magazine ad was essentially a “for dummies” explainer for adults. They knew that no kids were reading Parents Magazine, so the focus was less on fun than functionality.

But in trying to explain how simple it was, did they make it even more complicated? At the very least they could’ve arranged the numbers in a clockwise pattern, rather than zig-zagging all over the place.

In another strange design gaff, they “smooshed” the logo! This happens all the time in the computer age, because a thoughtless amateur can just grab a corner and stretch it as much as they want, but back then it took a little more effort to break common branding rules.

Christmas 1974

1974 was Odyssey’s best year yet, breaking the 100k barrier with 129,000 units sold!

But it was a rough year for Magnavox as a company. It were forced to delay its Annual Sale to March, though Di Scipio claimed it was due to the Sinatra special creating “unprecedented demand” that overwhelmed them with orders.

They didn’t even print a catalog for Annual Sale ‘74, which is disappointing because generic dealer ads indicate Odyssey was on sale for the clever price of $74.74.

Meanwhile, Magnavox stock continued to plummet. The Fall 1974 season began with Philips initiating a hostile takeover, gaining a majority stake in October 1974 and complete ownership by July 1975.

The catalog ads that year simply reused the assets from 1973, but what’s most notable this time is what’s not featured. The four newest game releases are gone, and the ones that remain are literally being given away. Magnavox clearly lost interest in the extras.

Ralph Baer believed the additional games didn’t sell because they were apparently hidden under the store counter, for staff to upsell customers who were purchasing a console. If true, that would make it impossible to sell new games to someone who already owned Odyssey.

But what if there was simply much more interest in the ball-and-paddle game? The additional packs were little more than glorified board games, offering additional overlays and game pieces to game modes already built into the console.

Maybe Magnavox saw the writing on the wall, which would explain the direction they went with the first Odyssey sequels — but we’ll get to those another time. Magnavox wasn’t finished with the core console just yet.

In a shocking move, Magnavox allowed their once-exclusive console to be sold by mail in the Sears Wish Book!

Naturally, this wasn’t something Magnavox pursued, but rather were talked into. Tom Quinn was a buyer at Sears who was fascinated with video games. He was in charge of sporting goods, but he justified going after Odyssey because it included sports games.

But he couldn’t convince them to allow Sears to sell Odyssey in their stores.

Magnavox also produced a new magazine ad for Parents Magazine, and then ran in a reworked form in Reader’s Digest. That they were targeting magazines primarily read by moms I think says something about who they felt had most of the buying power at Christmas.

I imagine it must’ve been a constant headache figuring out which two of the four basic family members should be playing in any particular ad. How do you suggest a gift for the kids, but that adults can enjoy it too?

Here they’ve apparently given up and decided all four should be playing. If you don’t know how Odyssey works, basically they’ve got two people controlling vertical movement, and their partners controlling horizontal movement. Which is a great idea if you want to get everybody arguing. On the other hand, there are modern hits like Overcooked.

I’ve been trying to generate theories on why the ad was reworked for Reader’s Digest. The page dimensions of that magazine were much smaller, but it doesn’t look like they actually increased the text size. It ran in the Gift Guide section of the issue, so that at least explains the change from “Get Odyssey” to “Give Odyssey.”

But there are two things I love about the first version that get lost in the second.

First, that killer headline. It’s based on an idea that goes all the back to the very first brochure (“With Odyssey you participate in television, you’re not just a spectator”), but it was never said better than right here. It’s so good that even the garbage subhead underneath barely injures it.

Second, the bold move to open the body text with a shocking statistic about the trouble with television, only to turn it around in the very next paragraph. This was a common strategy used in Volkswagen ads — though usually augmented with humor — which brings us full circle with Computer Space and the inescapable influence of car ads.

The Flop Fallacy

There’s a common misconception that Computer Space and Odyssey were flops. Failures. Fiascos. None of this is true.

I’d hesitate to even call them “commercial disappointments.” Both machines sold a reasonable number of units for the times, they just weren’t the culture-defining hits they could’ve been.

What held them back? In the case of Computer Space, the game was just a little too complicated to be someone’s first introduction to the concept of video games. College kids enjoyed figuring the game out, but bar patrons wanted something a little more pick-up-and-play.

The legend goes that the game was so complicated that no one wanted anything to do with it, but that’s simply not true. Nutting Associates manufactured around 1,500 at a time when that was an above average amount, and sold most or all of them.

If they hadn’t, they wouldn’t have made a sequel.

With an actual logo this time! And I guess Nutting decided sex was no longer selling, because he decided to replace the risque models with the game’s theoretical target demographic: teenage boys and girls.

Magnavox’s launch was more complicated. They beat their projected numbers, but produced way too many, which looked like a flop on paper. But then they sold through all the overstock and produced another run, beating the first year’s sales. And then the third year they beat the second year’s sales.

So why do these get labeled as flops?

It’s partly down to the initial overorders, of course. But also, it’s like we have this kneejerk desire to declare something a flop if something isn’t a hit — or sometimes isn’t enough of a hit.

Maybe we even believe that if something becomes obscure and forgotten, it’s a sign that it was a flop. But the truth is, we only ever remember the hits. After all, when we see a ball-and-paddle game today, we don’t call it “Odyssey” or “Table Tennis.”

We call it Pong.

[Continued in Part 3.]

Additional Sources: Billboard, Cash Box, FlyerFever.com, GoodHousekeeping.com, Hearings by the United States National Commission On Product Safety, New York Times (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7), Odyssey Museum, (blog and expanded book), Videogames: In The Beginning by Ralph H. Baer, Weekly Television Digest.

Special Thanks: Chris Chapman, Frank Cifaldi, Ethan Johnson, Gus Lanzetta, Alex Smith, and Wietse van Bruggen.

Kate Willaert collects video game history in her monthly newsletter.