School teacher Bonnie Berryman looked up as her son Brett hustled through the door of her classroom. He gave a cursory hello as he crossed the room to the desk holding her Apple II computer, where he dumped his backpack onto the floor and dropped into a chair.

The Apple II’s disk drive rattled. A moment later, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? appeared on the screen in black and green letters.

Berryman returned to grading papers while Brett leafed through a World Almanac. Occasionally he would ask her a question rooted in geography or world history, then go back to tapping keys. A moment later, the computer would trill a simple melody, signifying that Brett had correctly deduced where to travel next.

Brett had discovered Where in the USA is Carmen Sandiego? through a friend at elementary school, two blocks from the junior high where Berryman taught eighth-grade social studies in Minot, North Dakota. As soon as school let out, Brett walked the two blocks to his mom’s building and played Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, the first game in the series, on her school-owned Apple II.

His mother didn’t mind Brett playing computer games after school. Unlike coin-op games like Space Invaders, Brøderbund Software’s Carmen Sandiego series didn’t revolve around shooting aliens and setting high scores.

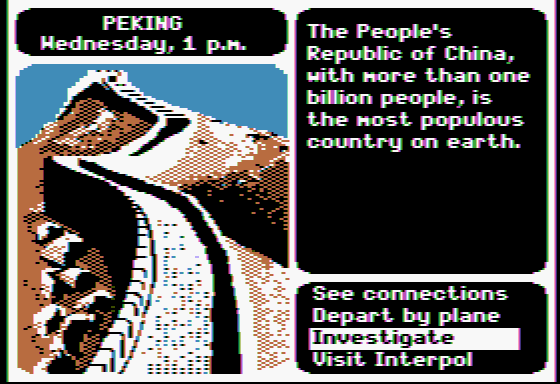

Instead, players are cast in the role of a detective tracking down the notorious Carmen and her band of thieves, beginning each case by investigating their current location and interviewing witnesses. The clues they receive are couched in geographical and historical trivia: a witness may say they think the suspect was headed for the Eiffel Tower, or sailing down the Danube.

Players unravel clues by doing research — consulting friends, parents, teachers, and texts such as encyclopedias and almanacs — to determine where to travel next to continue their search. If they follow the breadcrumb trail correctly, they eventually make their way to the thief’s hideout and apprehend them before they can abscond with their stolen treasure, usually an artifact with historical significance.

“One day when he was playing, he says, ‘We should have one of these on North Dakota, Mom,'” Berryman remembered.

During the drive home, Berryman mulled over Brett’s idea. A Carmen game based on North Dakotan history had merit. Many teachers she knew had an Apple II in their classrooms, and the Carmen games had been popular among kids of all ages since their debut in 1985. Now it was 1987, two years out from North Dakota’s centennial. Teachers from all across the state had been brainstorming ways to get students interested in their history. A history lesson disguised as a computer game seemed just the ticket.

Excited, Berryman called Craig Nansen, Minot Public School District’s director of technology. Nansen grew thoughtful as she pitched him on approaching Brøderbund, the game’s publisher, about making a version of Carmen unique to North Dakota. If this worked, he thought, the state’s schools and teachers stood to gain exposure. Maybe even a visit from the President.

”It was kind of like this moonshot type thing,” Nansen admitted. “But as we thought about it and talked about it, we ended up pursuing that with our state legislature. We contacted Brøderbund, got a lot of different people involved at the Department of Public Instruction.”

Nansen and Berryman headed up the project. Their next step was organizing a meeting of fourth- and eighth-grade history teachers in Minot. Although social studies was offered at every grade level, Minot Public Schools required teachers of those grade levels to incorporate a unit on North Dakota into their lesson plans. At the meeting, Nansen and Berryman outlined their proposal: Any interested teachers would form a committee to gather trivia and other materials, then submit it to Brøderbund for use in making a Carmen game set in their state.

“We let them know that it would be time-consuming, that there would be work to be done,” Nansen said.

Several teachers expressed hesitation. Computers were new additions to their classrooms. Many let them sit unused, unsure how to even turn them on. “We weren’t totally interested, because we felt like that’s beyond what we could do,” recalled Shawnee Voiles.

Thirteen teachers pledged their support. The newly minted committee set about discussing ways to gather information on North Dakota. Nansen would act as coordinator, keeping tabs on budgets and deadlines, and being a point of contact with Brøderbund and state representatives.

“The people on the committee are the ones that really ended up doing the work,” Nansen said. “They were the ones that were the curriculum experts. They were the people who knew North Dakota, who knew all of that information. So once the project became a reality, all I pretty much did was schedule the meetings and made sure people were there and arranged for some things.”

Where in the world is Brøderbund?

Carmen Sandiego is notorious for remaining one step ahead of Interpol, countless police departments, and the ACME Detective Agency, the coalition of player-detectives who dedicate classroom sessions and after-school hours to recovering the priceless artifacts she and her minions steal.

In 1989, Brøderbund Software was much easier to find.

Thanks to the global acclaim of their products, Brøderbund had spread out over five buildings in an office park based in San Rafael, CA. In 1981, business software had accounted for 40 percent of its revenue. Even then, co-founders Doug and Gary Carlston strove to diversify, offering everything from games to their most successful software, The Print Shop.

“In the early days, everyone was trying to be everything,” said Doug Carlston. “Even Microsoft was doing flight simulators and all kinds of silly stuff in the early days, because they didn’t know what they wanted to be, either.”

Ideas for the first game, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, came from several people. It started when programmer Dane Bigham wrote a menu-driven adventure game interface, in response to most adventure games being driven by text commands. He collaborated with artist Gene Portwood to develop a concept centered on cops and robbers.

Gary Carlston saw potential in Bigham’s graphical menus, and suggested Dane and Gene use the interface to create a trivia game centered around a World Almanac that would be bundled in with the product. Artist Lauren Elliott was also collaborating with Gene Portwood on a separate game concept, a scavenger hunt called Six Crowns of Henry VIII, and from his perspective this was an extension of that project.

“They’re going to toss this book in,” Elliott remembered. “So, we took that original idea and built the game around it.”

Brøderbund contracted David Siefkin, a freelance writer, to draft a treatment for a game about a master thief and a band of minions that players would have to tail and arrest one by one.

“Before I wrote the script for the game, I had traveled around the world for nine months, having to learn about different currencies, languages, customs, and landmarks. I wanted a game that introduced these things to young game players, and hoped it might inspire them to make similar trips,” Siefkin told me. “I also imagined that players would use trial and error to track the villain, and that they would learn about the world from their experience.”

Siefkin’s script included a list of suggested names for the organization’s mastermind. One was a woman named Carmen Sandiego.

Brøderbund’s product manager Katherine Bird—known as Cricket to her colleagues—took to the exotic-sounding name and character.

“One of the things that irritated me about the games industry was that at the time it was so heavily focused on males, boys,” she explained. “If you were playing a game, the reward would be getting to the castle and finding the very busty princess. I and a number of other people were trying to make a broader game that was fun for everybody.”

Cricket worked with a female colleague to write hundreds of clues that players would have to decipher, with Elliott and Portwood chiming in on design.

“Gene used to say, ‘Kids are short, not stupid.’ They knew if they were being drilled on something,” Elliott said. “All the crap at the time was, you know, ‘Which of the following three answers is correct? No, do it again.’ So, Carmen was the first, I think, that had a character to it at all.”

“We tried to have a really diverse range of characters in the game,” added Cricket. “That was another goal.” Carmen got her name on the box, but all of her henchmen were given catchy names, though the famous pun-based names didn’t start trickling in until the second game, with character such as Ken Hartley Reed (“Can hardly read.”) and Polly Esther Fabrique (“Polyester fabric.”).

Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? wasn’t an immediate hit, but picked up steam after teachers adopted it as a teaching tool. Brøderbund capitalized by cranking out follow-ups based on World’s blueprint: players start in a location, investigate landmarks and talk to witnesses to gather clues, then research their findings and head to another location—a process they repeat until they arrest a criminal and begin the next case.

As the franchise grew in popularity, Brøderbund was inundated with mail from teachers who sent lesson plans written around letting their kids play Carmen games during class. Those lesson plans were discarded until Cathy Carlston, Doug’s and Gary’s adopted sister and honorary co-founder, recognized them as a gold mine; one where teachers did the mining—research into specialized areas—for them.

“And we finally realized, well, wait a minute, we’ll take the lesson plans, contact these teachers, put their names in the final edition in the credits [of the Teacher’s Guide edition],” Elliott said. “So the teacher worked like a sonofabitch and spread the word, and then you gave them the copy, and in the software you had a coupon to go home with the kids’ families so they could buy it directly. It was a very intelligent thing for Cathy to start.”

Cathy was methodical in her work. Through outreach, she formed a network of teachers who were eager to submit information to Brøderbund. Her effort in building a grassroots network of teachers set the stage for Where in North Dakota is Carmen Sandiego?, designed by teachers, for teachers.

“We got an inquiry from a teacher in North Dakota who said, ‘Hey, we really like your game. We’d love to do something similar and teach our kids about our state,'” Cricket said. “I don’t know if he [Craig Nansen was the one who] had contacted me or what, but I thought Oh, that sounds fabulous. What a great, fun idea.”

Brøderbund had a template for the Carmen franchise. If Minot’s teachers were willing to supply trivia, the studio’s in-house team could turn out a custom game. They also got a kick out of the notion of Carmen Sandiego, infamous plunderer of some of the world’s most prestigious and historically significant artifacts, hiding out in North Dakota of all places.

“I think that was part of the attraction, that it was North Dakota, for all of us,” Cricket continued. “It was like, oh, this is kind of random: Not New York or Illinois. It was fun.”

Craig Nansen had sent a proposal to North Dakota’s Department of Public Instruction, which had forwarded it to the state legislature. State politicians had responded with a grant for $100,000 to be split unevenly: $80,000 would go to Brøderbund, and $20,000 would be dispersed among the committee of Minot teachers as compensation for time spent working on the game. Brøderbund’s developers would handle programming, artwork, and manufacturing, since the Carlstons had a pipeline in place for just such an endeavor. Nansen also asked that Brøderbund sell them 2500 loose disks, which they would distribute to teachers all across North Dakota.

Not everyone on the Carmen team met the proposal with enthusiasm.

“Gene was a little against the idea. He was very much a character-driven guy,” Elliott recalled of Portwood, who had started his career as an animator at Disney working on ’50s classics such as Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, and Sleeping Beauty. Portwood left Disney and the animation field in general in order to support his family, but found himself doing computer animation a few decades later at Brøderbund.

“Gene was instrumental in turning Carmen into a real character,” Elliott continued. “So, when something like North Dakota came along, he wasn’t quite sure that you could maintain the level of—she was after famous stuff, and was North Dakota famous enough?”

Portwood came around when he remembered that Disney licensed its characters to media such as educational films. That winter, he flew to North Dakota to scout it as a viable setting. He phoned Elliott, who asked how the trip was going.

“It’s freezing,” Portwood chattered. Elliott coaxed more details out of his friend, who said the weather was blustery and, he reiterated, cold. Portwood concluded his report by asserting that Brøderbund would be hard-pressed to come up with 100 interesting facts about North Dakota, a pastoral but largely featureless state with one of the lowest populations in the country and few major tourist attractions outside of state parks.

Fortunately, coming up with factoids was the teachers’ job. All Brøderbund had to do was connect the dots, and a few programmers believed doing so would be simple thanks to an ongoing experiment. “At some point, when Carmen was successful, the company was going to go a couple different directions. There were ideas to come up with a Carmen toolkit,” Elliott said.

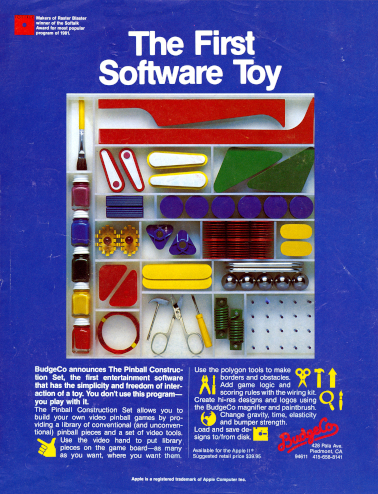

The concept of developing a toolkit that would let Brøderbund’s developers quickly piece together new games in the series was so short-lived that no one can quite remember how it was planned to take shape. As Elliott remembered it, the Carmen toolkit would have been modeled after the success of products such as Pinball Construction Set, a game published by Electronic Arts where players built their own pinball tables using bumpers and other components. A Carmen toolkit would be used internally at Brøderbund to facilitate quicker development of new entries in the series: take trivia and graphics, and plug them in to bake games in the mold of Where in the World. If it panned out, the toolkit might be something Brøderbund could sell, just like EA’s do-it-yourself pinball game.

Doug Carlston had a different recollection. As his memory served, some of his programmers pitched him on creating a game engine for Carmen titles. The idea was to leave the engine’s technological underpinnings more or less intact from game to game, but insert new data such as location images and text-based clues and prompts. “Programming has always been expensive, and it was fairly expensive even on simple programs like Carmen Sandiego,” explained co-founder Doug Carlston. “Some of the guys there said, ‘We basically have it down to an engine, just with a set of data we can [use to] make a whole new product.'”

When a few company programmers held up Where in North Dakota as a potential guinea pig for their engine, Doug compromised. If they could turn out a game according to Where in the World’s template, on time and on or under budget, he would give the green light to develop engines for other types of games.

Educating the educators

A Carmen Sandiego game set in North Dakota was not the Minot school system’s only attempt at writing software for the purpose of educating students. “MECC had a product out called MECC Dataquest, and we were going to go ahead and start gathering all this information about North Dakota and put it into a database,” said Nansen.

Short for Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium, MECC was an organization of teachers and other individuals such as administrators and programmers interested in evangelizing the use of computers in education. The group’s Dataquest program let users input information into a database for personal or professional use. A committee of teachers in North Dakota proposed the database to the State Department.

The finished database consumed 17 floppy disks, with one of them – “Carmen’s North Dakota Almanac” – acting as a semi-canonical tie-in to the game. Collectively, those disks formed a compendium that would give students a leg up when they sat down to play Where in North Dakota is Carmen Sandiego?.

“We made all these databases, and then the kids could refer back to the databases as they’re playing the game to find information,” said Mary Littler, one of the Minot teachers on the game committee.

The database would serve another purpose. To make sure teachers were prepared to incorporate the game into their lesson plans, representatives from every school district in North Dakota would need to attend a workshop conducted by the game committee. Upon completing the workshop, they would receive materials including the game and database.

Before they could lead workshops, however, the teachers had some learning to do themselves. “Up until that point I would say that most of the schools had a central area with, I don’t want to call it a lab, because it might have only been between five and twelve computers,” Nansen said. “So, the idea of having one in their classroom, that was pretty neat.”

“We didn’t even know how to turn them on,” Berryman admitted.

Computers appeared in classrooms at varying rates, and many businesses pitched in to increase adoption. Supermarket chain Piggly Wiggly ran a promotion where customers could submit a certain number of receipts in exchange for an Apple IIGS. “They all came with little brass plates [that read] Donated by Minot’s Piggly Wiggly stores or something,” Voiles remembered.

Nansen, who had canvassed the tech and education fields with news of the game’s development, did his part to help the teachers become computer literate. “One of the other things we had done too was contact Apple Computer,” he explained, “and Apple Computer donated a computer for every classroom of those people that were on the committee. And in fact, Phyllis [Landsiedel] is reminding me that we even had a drawing at the end, and one person got to get their own personal computer from Apple.”

Landsleedle had good reason to remember that sequence of events: When the drawing took place, she held the winning ticket. “I took it home. I had it at home as my private thing,” she said of the Apple II. “And I learned how to [type] and to hit the right button after a lot of errors.”

Brøderbund pitched in by donating a copy of The Print Shop to Minot’s committee. The teachers put it to good use, creating posters, advertisements, and other materials for classrooms as well as their workshops.

Bringing the World to North Dakota

While they were aware that Brøderbund expected data to be submitted according to guidelines, the teachers insisted on rethinking certain series staples. Instead of hopping on a jet to investigate new locations, students would drive. Carmen and her band of ne’er-do-wells also underwent a change.

“One of the things where we got our way with the Brøderbund game is that, being an educational product, which we were looking for, we didn’t want Carmen to be a criminal,” said Nansen. “So, in this version of the game, Carmen is a prankster. And everything that is done is playing pranks.”

The teachers delighted in coming up with pseudonyms for the criminals-turned-pranksters. Many of the names doubled as allusions to state history. Craig Nansen became C. R. Parks, a nod to attractions such as the Theodore Roosevelt National Park in western North Dakota. Don Feldner, who taught social studies at a middle school, created L. E. Vader, a pun on “elevator,” which one had to ride to get to the top of North Dakota’s capitol building.

“I was Rich R. Dirt,” explained Gloria Lock, a fourth-grade teacher at the time. “I wanted to be Rich Chernozem, but everybody thought chernozem was too hard and nobody would know it. Chernozem is the name of the rich dirt,” she added, naming a type of soil found in the east.

Leaving hands-on work to the teachers, Nansen coordinated work sessions and wrote and distributed memos to keep everyone up to date. Brainstorming sessions occurred during meetings. Part of those sessions involved assigning topics and sites. “I think we each had a topic. I know mine was Agriculture. I did that on my computer in my classroom after school,” said Phyllis Landsiedel, who was also fourth-grade teacher.

Research entailed more than making up clues. Lock tackled Government, which meant that if a case led students to Bismarck, the state capitol, she was in charge of devising reasons for the pranksters to be there. Other trivia could be so obscure—such as “gandy dancer,” slang for railroad workers and a term very likely to be unheard of to the game’s target audience—that accompanying history texts, assembled by the committee for inclusion with the game, were practically mandatory. Landsleedle and other teachers had accumulated a wealth of information on North Dakota, but had made most of it themselves. North Dakota was such a small state that even book publishers steered clear of it, certain that publications on the region would lose money.

What they lacked in ready-made materials, they made up for in ingenuity. Nansen mailed letters to mayors of each city and town, asking them to fill out questionnaires from which the team extrapolated more facts. “When I wrote to all the cities, I asked them to send brochures, tourism things,” recalled Shawnee Voiles. “So, we’d send them to Brøderbund, and that’s how they made the ‘beautiful’ color pictures on the screen at each location.”

Every clue and document underwent peer editing and fact checking, though the committee took some good-natured creative liberties. Researching regional sports teams in the state, Landsleedle sneaked in mention of the Kenmare Yellow-jackets—a mash-up of high school teams Mohall Yellow-jackets and Kenmare Honkers. As both cities were located in the greater Minot area, residents enjoyed the rivalry between their teams. Landsleedle, a Kenmare native, knew that her intentional misappropriation of the Yellow-jackets would rile up her family members in Mohall. Sure enough, she received a phone call from her cousins after the game’s release.

From there, Minot’s team sent materials to Brøderbund for editing. Cricket, as Product Manager, was among the first to review their writing. She made notes and suggestions regarding the game’s instruction manual, then returned them. Minot applied the changes and added more information, then sent back fresh revisions. Back and forth they went, the script growing with each round, until Cricket returned final copy with a note that read, “The Brøderbund design services staff would like to humbly beg that no more changes be made, only corrections. Thank you, thank you, thank you,” followed by three smiley faces.

“Oh!” Cricket exclaimed, not recalling her note. “Irritable, huh?”

“Well, as we got into it, and then of course making changes and modifications, they were having to retype everything that we were sending them,” Nansen explained. “So eventually they sent us a prototype of a database that we had to enter information into it. So then they didn’t have to do the retyping.”

“They realized early on they would make no money, and we were kind of high maintenance,” Voiles admitted.

High maintenance is one way to describe Minot’s cohort of moonlighting game designers. Dedicated is another. The committee worked on the database and their Carmen game from 1987 through much of 1989, while teaching full-time. After students filed out for the day, they had assignments to grade, lesson plans to fill out, exams to write. Around dinnertime, the teachers switched gears to Where in North Dakota. Some worked in their classrooms, taking advantage of the peace and quiet. Others convened at Nansen’s office, ordering in pizza and cranking out clues.

“We were up at Craig’s office many nights until 11, 12 o’clock because we had deadlines to get done,” Littler remembered. “And [not] all the teachers could come each night,” she added.

Work on Carmen didn’t stop when students left for summer vacation. No classes to oversee meant more time to devote to the game. Over June, July, and August of 1987 and ’88, most work sessions lasted until well past midnight. Saturday meetings became the norm as deadlines approached.

Once the game content had crystallized, they held a “copy party.” Committee members met up to mass-produce copies of the 17-disk database, enough for school districts across the state. While some teachers copied disks, others applied labels, while another organized them.

“No ability on the computer, and typing all my stuff in one finger at a time and then pushing the wrong button and it’s all gone. Crying a few times. It was exciting,” Lock recalled of the copy party.

“I wanted to quit several times,” Voiles said of the two-year writing and production process. “That’s one of the first times in my career that my husband Terry said, ‘I don’t think you should quit this. I think you need to hang in until the end, because you’ll all be glad that you did.’ And we really were. But it wasn’t easy, and it was time-consuming.”

Reviewing all of the evidence

With revisions finally locked down, the Brøderbund machine kicked in, producing the 2,500 disks as dictated by the contract, a teacher’s guide, and a manual. A fully-assembled kit could also include a custom almanac (designed by the Database Committee in The Print Shop), lesson plans, and the 17 database disks.

The game was released on February 23, 1989, just in time for North Dakota’s centennial that November.

Minot’s committee of teachers had finished writing and producing copies, but the next phase was just beginning. Traveling in groups, they carpooled from school to school, educating teachers on the game and their database, and how to integrate them into curriculum. “They could not get the material until they’d attended the workshop, which was really a good thing for us,” said Berryman.

“We taught them how to use a computer,” Voiles added. “Many teachers had never even understood what a database program was. We really didn’t until we had to make them.”

Workshops took place over Friday evenings and part of Saturdays. That, and a $150 fee, got attendees a binder of games and materials.

Kids who completed the entire game could send for a certificate as proof of their accomplishment. For the committee, seeing kids excitedly poring over maps was accomplishment enough.

“To me the best thing about this game was we taught North Dakota studies for years,” Landsleedle said. “And you’d try to get the kids involved with all kinds of projects. And they were involved. But with this project, they learned North Dakota, and they loved every minute of it.”

Outside of North Dakota, Where in North Dakota holds the dubious honor of being Brøderbund’s lowest-selling game, and perhaps its lowest-selling product, rivaled only by Food Cost Explosion, a business product that sold roughly a dozen copies, according to Doug Carlston.

Although Brøderbund offered a retail version of Where in North Dakota for $34.95, it was never listed in the company’s product catalog of that era. The game could be ordered via mail-order form, but Carlston remembered retail sales never increasing beyond single digits. “It was not something that even made it into the rounding error in the finances,” he said.

Brøderbund didn’t earn enough money to cover the project’s engineering and manufacturing expenses. Therefore, Carlston had no choice but to deem the internal engine/toolkit experiment a failure. “They were disappointed, but there were a lot of other things to do, and I also worried about tying up too many of our relatively small programming teams doing things that weren’t really breaking new ground at all,” Carlston said.

Despite the outcome, Brøderbund’s co-founder doesn’t regret the trial run. “Sometimes you can be dictatorial and say, ‘I’m just not going to let you do this,’ but sometimes it’s good to let a team fight their boss and prove that he’s wrong.”

Even if North Dakota had sold well enough to justify green-lighting engines for Carmen and other games, Doug and Gary Carlston’s word may not have been enough to justify such ventures. Brøderbund had grown from a few siblings mass-producing disks in Gary’s living room—the Carlstons’ place of business before relocating to San Rafael—to an enterprise that employed hundreds of people. Operating such a scale meant that whims and risky propositions had to take a back-seat to more conservative decision making.

“It’s just the evolution of the industry went that way,” Elliott said, “and there was a whole era there where a whole lot of people, Gene [Portwood] and myself, all kinds of authors left because they renegotiated all the contracts to zero out any royalties for the authors.”

Fiscal outcome aside, Where in North Dakota is Carmen Sandiego? remains a project near and dear to the hearts of those who made it, including Brøderbund developers. “I’m glad that they got to do it,” said Elliott. “It sounded like more of an exercise for the teachers than anything. It got everybody involved, it seems like they had fun, and got their names in it.”

North Dakota kept its favorite game in circulation until schools upgraded equipment, trading Apple II machines and floppies for Macs and CD-ROM. The committee kept Where in North Dakota on life support, cannibalizing parts from dead Apple IIs and slotting them into computers still chugging along. Eventually they used emulators on modern PCs to run the game – until the trivia became so outdated that it was no longer useful.

Twenty-eight years after the game’s publication, most committee members have retired. Where in North Dakota’s existence almost went unnoticed by any except those who worked on it.

In March 2014, Doug Carlston donated his collection of Brøderbund products and memorabilia to The International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG), curated and maintained by The Strong museum in New York.

One of the reasons for ICHEG’s founding is to make its growing compilation of gaming artifacts available for researchers. While examining Carlston’s donations at The Strong, Video Game History Foundation founder Frank Cifaldi noted that Where in North Dakota was missing. Cifaldi tweeted about the game, explaining that he’d only recently heard about it and requested information from anyone who had more details.

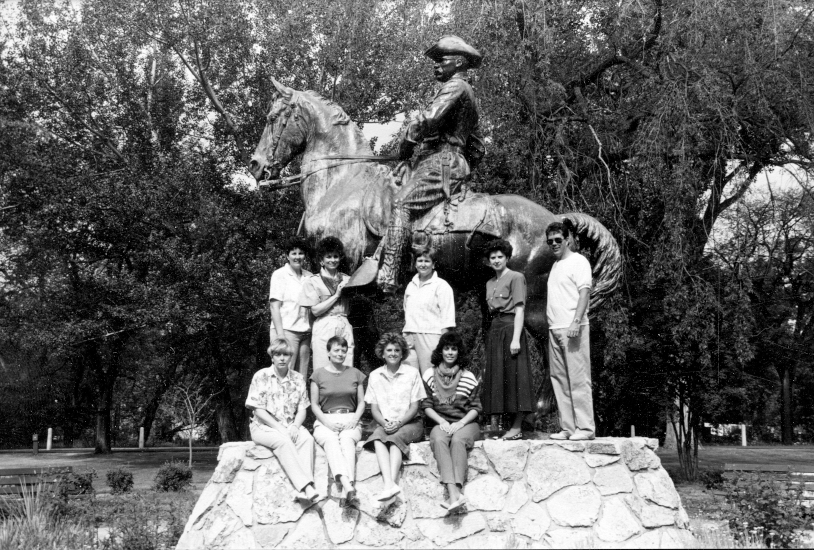

That tweet initiated a domino effect. Former Minot school district administrator Craig Nansen noticed Cifaldi’s tweet, wrote him back, and arranged a sit-down conversation with as many of his ex-design colleagues as he could locate. As it happened, Nansen and others had been reminiscing about the game over email.

Afterwards, Cifaldi spoke with Doug Carlston, Katherine “Cricket” Bird, and Lauren Elliott about Where in North Dakota as well as Carmen Sandiego history in general. Sadly, Cathy Carlston and Gene Portwood were unable to share their experiences. Cathy Carlston passed away in 1995 from colon cancer. She was only 39. In the summer of 2000, Portwood died of a heart attack in a hospital where he was recovering from a stroke he had suffered a year earlier.

Cifaldi’s interview with the Minot committee gave them a forum where they could wax nostalgic about the project that many consider their greatest professional achievement.

“You know, I’ve never included it in my resume. I should have,” Berryman said.

“Bonnie was the creative genius that got the idea going,” Voiles said.

Berryman demurred. “I just got it started, and you guys carried the ball, and it’s fantastic. I mean, it was fun, it was really fun.”

“That’s just how committed we were,” Voiles said. “We wanted this out in classrooms with kids and teachers. It was pretty darned impressive that we did this, and made it happen, I think. It’s probably one of the biggest accomplishments of most of our careers.”

On that point, Berryman agreed. “We had this baby, and we wanted to see what it looked like.”

Thanks to everyone who contributed to the making of this article, including but not limited to: Brian Kent, Kate Willaert, Wesley Fenton, Kevin Bunch, and 4am.

All of this research was made possible by donors just like you! If you’d like to support the preservation of video game history like this, consider donating today.