Before Pong there was Odyssey, the first home video game console. When Magnavox released it in the fall of 1972, they encountered a number of obstacles in educating consumers about this brand new technology. Odyssey creator Ralph Baer recounted in his book, Videogames: In The Beginning:“Magnavox featured Odyssey in their fall TV advertising in such a way that everyone got the impression that the game would only work with Magnavox TV sets. … On the positive side, a television commercial featuring old “Blue Eyes,” Frank Sinatra, helped spark up sales in the fall.”

Numerous video game history books and articles have referenced these revelations, sometimes conflating the two into a single commercial. But was it? Did Sinatra have a role in confusing consumers? And what exactly was said that confused consumers?

Originally this was going to be the first in a series for GameHistory.org about early video game ads in print (watch this space), but it felt important that I address these lingering questions, and one other:

Could I track down the first Odyssey commercial?

Fits Any Brand TV

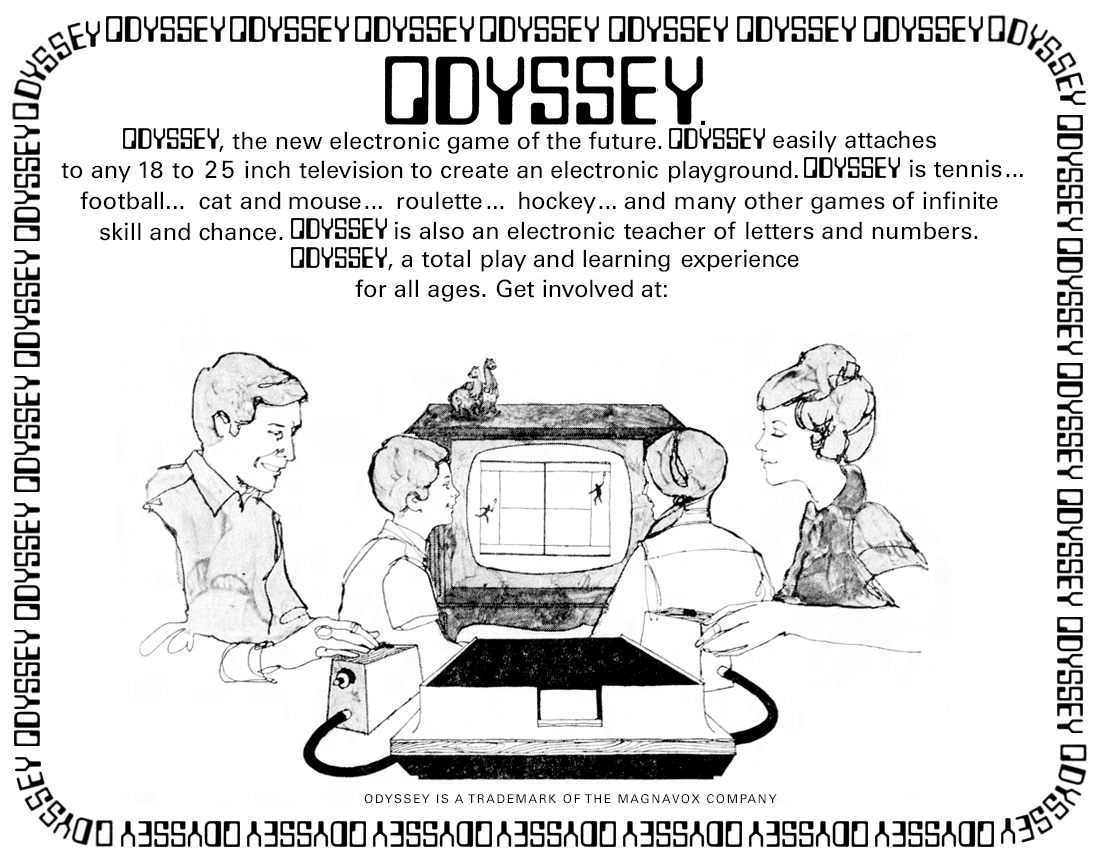

Odyssey by Magnavox (not “Magnavox Odyssey” or “the Odyssey” — simply “Odyssey,” like the band Talking Heads) worked a little differently from modern consoles today.

Although you inserted game cards into the console similar to a game cartridge or disc, the cards didn’t really have any games on them. All the game modes were built into the console, and the cards just let you select each mode, like a more cumbersome switch or dial.

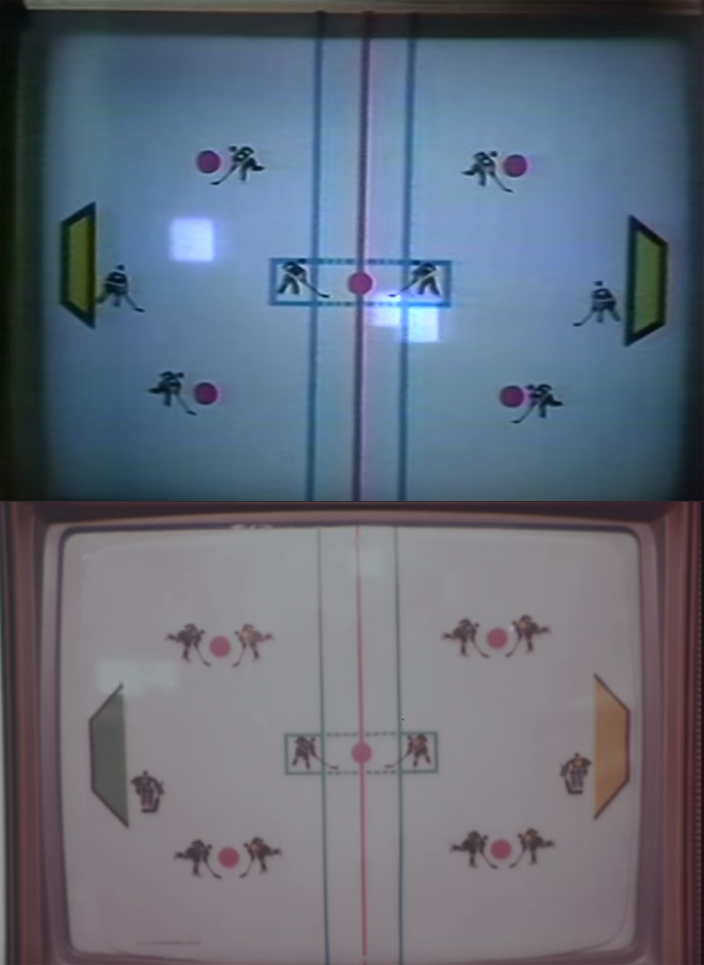

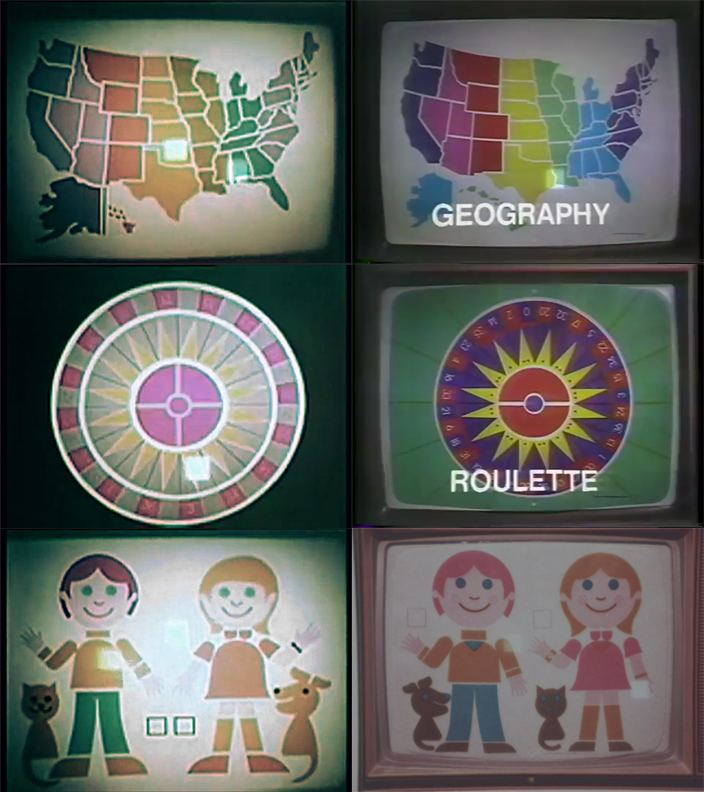

Every game mode was a variation on player-controlled white dots or paddles being moved around on-screen. Instead of color graphics, the box came with a set of transparent overlays that attached to pre-HDTVs via static electricity (with a roll of tape included just in case).

This is the most common Odyssey commercial on Youtube. The earliest Youtube source for the video says it came from The Carol Burnett Show on February 10, 1973, which is pretty close to the fall 1972 launch. Could this be the first commercial?

Except there’s nothing in this commercial that’s confusing. Not only does the announcer clearly say it “easily attaches to any brand TV,” there’s even large text displayed on the screen while he says it, with the words “any brand” underlined for additional emphasis.

This seems more like a reaction to confusion. Clearly I’d have to go back further.

The Electronic Game Of The Future

Odyssey went on sale some time between late August and mid September of 1972. It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact day because electronics didn’t have street dates like we’re used to today.

I can confirm that Magnavox’s marketing campaign for Odyssey kicked off around mid-September, when the earliest Magnavox-produced newspaper ads began appearing. Commercials may have started airing the same month, but that part I’m unable to confirm.

However, there is one major TV appearance with a date that’s confirmable, if this episode guide can be trusted. On October 16, 1972, Odyssey was featured on a segment of the game show What’s My Line?

Panelists: “Ohhhhhhhh…”

Panelist #3: (“Playing Tennis…?”)

The show assembled a different celebrity panel each week, who had to figure out what the guest does. A week’s worth of episodes were taped in a single day and then aired a few months later.

According to the episode guide, the Odyssey segment was recorded on August 24, 1972. This is important because, as I mentioned, the marketing campaign didn’t appear to kick-off until mid-September. The episode was taped before the panelists could have seen a single ad for Odyssey, making this the first time any of them had seen a video game hooked up to a home TV set.

The segment makes things a little more interesting by asking the panelists what the guest and host are currently doing, rather than asking what the guest does for a living. “Playing tennis” is an easier answer than “I sell a device that you hook up to a TV to play Tennis.

They had to answer “tennis,” of course, because Pong hadn’t been released yet. For that matter, the term “video game” hadn’t even been coined yet, so they couldn’t say that either!

Think about that for a second. These are terms and concepts that we take for granted to such a degree that it’s difficult for us to imagine anyone not knowing them. How could someone watch two people sitting in front of a TV with controllers, and not recognize that they’re playing video games? This video is a fascinating historical document of people being introduced to these concepts for the very first time, before the terminology had even been established.

Naturally, the panelists were unable to guess correctly. Once the answer was revealed, product manager Bob Fristche was given some time to explain how Odyssey works, with prompts from host Larry Blyden. One prompt in particular stuck out to me:

Larry Blyden: Can you use it on any television set at all?

Bob Fristche: Yes, it works on any TV. Primarily 18 inches through 25 inches. That’s by design of the overlays that we have for the product right now, but certainly it’ll work on any TV.

It turns out this was actually a common Odyssey talking point. The launch newspaper ads said, “Odyssey easily attaches to any 18 to 25 inch television.” The in-store promo film said, “Odyssey can be attached to any brand television receiver with a screen size of 18 to 25 inches.” And every reporter who wrote about Odyssey demonstration earlier that summer made a point to say it works on any TV set, suggesting it was part of the messaging as early as May 1972.

In other words, Ralph Baer must have been mistaken. Which is completely understandable, given that human memory is much less reliable than we’d like to believe, and especially several decades after the fact. But if the ads didn’t cause the confusion, what did?

Five years after the release of his book, Baer was asked about the topic in a Youtube interview with Video Game Saga. This time he speculated a different reason:

[The commercials] show Magnavox’s attempt to show that it’s a universal piece of equipment that can be attached to any set. But, initially there was this problem. Magnavox’s television sets and radios were sold largely by company-owned or company-controlled stores. And someone got the idea wrong at first, and I was kind of critical of that, too. But they fixed it along the way.

In short, consumers believed Odyssey only worked on Magnavox TV sets because it was only available in Magnavox stores. This makes a certain amount of sense, given their unfamiliarity with closed-circuit devices. Consumer VCRs hadn’t arrived yet, so the closest reference point people had were either signal-boosting antennas that worked on any TV, or early remote controls which only worked on specific model TVs. Since the controllers loosely resembled remote controls I speculate this was a major cause for the compatibility assumption.

But this wasn’t the only interesting detail to come out of the above Youtube interview…

The First Video Game Commercial

While discussing the commercials, Baer offered this:

Well, if you want to publish something…if you want to, I’ll show you several commercials. They’re short, about 30 seconds long. They don’t take much memory, so I can send them by email if you want.

Sadly, it appears he only sent them one clip, but it was a very important one.

Video Game Saga used it as a video backdrop during the interview, but thankfully also uploaded an isolated version, albeit stretched horizontally (a huge pet peeve of mine). I decided to put some time into cleaning it up, restoring the original aspect ratio and attempting some color correction. It’s not perfect, but it’s an improvement.

The biggest obstacle I encountered was that everything took on a red hue after fixing the white and black levels, indicating a significant amount of cyan loss. Film is made up of overlapping layers of cyan (light blue), magenta (pink), and yellow to create a full spectrum of colors. In aging film from the ‘70s and earlier that isn’t stored under absolutely perfect conditions, it’s not uncommon for the cyan layer to fade faster than the rest, resulting in a red hue.

You might notice in the original uploaded version that white elements have a cyan look to them. When the film was transferred to telecine, they likely used a cyan filter on it, which is commonly used as a quick way to make red film look a little more natural.

I wanted to do better than that. But I’d never color corrected red film before, and most the resources I found on the internet were only half solutions. I ended up using Dr. Dre’s Color Correct Tool paired with Photoshop and a lot of fine adjustment to try and reach an acceptable range of color. Like I said, it’s not perfect, but it’s an improvement.

I also re-synchronized the sound, based on a copy of the file Ralph Baer donated to the Strong National Museum Of Play. A comparison reveals that Video Game Saga trimmed out some “empty space” at the beginning and end, and when they did so, must’ve accidentally desynchronized the sound by half a second. For example, in the Strong file there’s an audible click near the beginning when the mother presses the button on the controller, but in VGS’s edit you hear it before the controller is on screen.

The trimmed out portions were a film leader at the start, and several additional seconds of blank star field at the end. I assume the star field existed so local dealers could superimposed their store name and phone number.

Initially I wasn’t sure whether this commercial was filmed before or after the 1973 “Any Brand TV” commercial, so I decided to compare them frame by frame. That’s when I first realized just how special Ralph Baer’s little gift was.

The first difference I noticed — aside from the change in narrator — was the differing frame rate. Movement in the 1973 commercial seemed “smoother,” like you’d see on a soap opera, game show, or live television. This is called the “soap opera effect,” and indicates that the 1973 commercial was recorded on video, which has a higher frame rate than film. It also doesn’t have the cyan loss problem of film.

My next question was: why video? A survey of early ‘70s commercials on Youtube suggests that most high budget commercials were recorded on film, possibly for the “cinematic” look. Could the 1973 commercial have been a quick low-budget replacement in order to emphasize “Any Brand TV?” The minimalist set in the 1973 commercial sure seems lower budget…

Next I looked up every 1970s Magnavox commercial I could find. They regularly made commercials for all their products, most frequently new models of television sets. What I discovered was that every Magnavox commercial from 1972 and earlier was recorded on film, and every one from 1973 onward was recorded on video. This filled me with additional questions, but did confirm one important detail: Ralph Baer’s commercial was definitely from 1972.

But it gets even better.

While comparing screenshots, I discovered the overlays in the first commercial are all wrong!

At first I thought the colors looked so different because of the cyan loss, but the differences go beyond color. Look at Hawaii on those two maps…it changes size! Most noticeably, Simon Says (compared here with the in-store promo film on the right) originally had the figures mirroring instead of matching each other!

In other words, we’re looking at prototype overlays! There are minor differences in almost every overlay shown, and they’ve been sitting here in plain sight for years.

When the product itself hadn’t even been finalized, I think it’s more than safe to say we’re looking at the very first video game commercial. And if there was any remaining doubt, I eventually learned that Baer himself had helpfully labeled his file “Odyssey Commercial 1 (Telecine).”

But There Are Always More Questions

Q: So wait, if consumer VCRs didn’t exist in the early ‘70s, how are there tapes of these commercials on Youtube?

A: I asked Fabtv, the uploader of the 1973 commercial, who told me:

There are several scenarios these tape-sourced clips can come from. Either copies made from the master tapes of the original programs in which they appeared — these were sometimes acquired for guest performers on the programs for their personal archives — professional taping services that recorded off-air programs for industry use, or videophiles that shelled out for the 3/4″ Umatic machines which came out around 1969, primarily for industrial use but also used for office copies of programs for many production companies that produced television programs.

In the case of the Odyssey ad, this was sourced from a VHS tape probably run off the original 2″ quad master tape for one of the show’s guests, who I’ve done archiving work for.

And that’s just for tape-sourced clips. For decades, collectors have saved and traded bits of 16mm film acquired from television networks, sometimes from the dumpster.

Getting that answer was easy, but others aren’t.

For example: why did Magnavox commercials switch to video in 1973? My initial theory was cost-cutting, but now I wonder if it was because the smoother frame rate made the featured model TV’s screen look better. It could be any number of reasons.

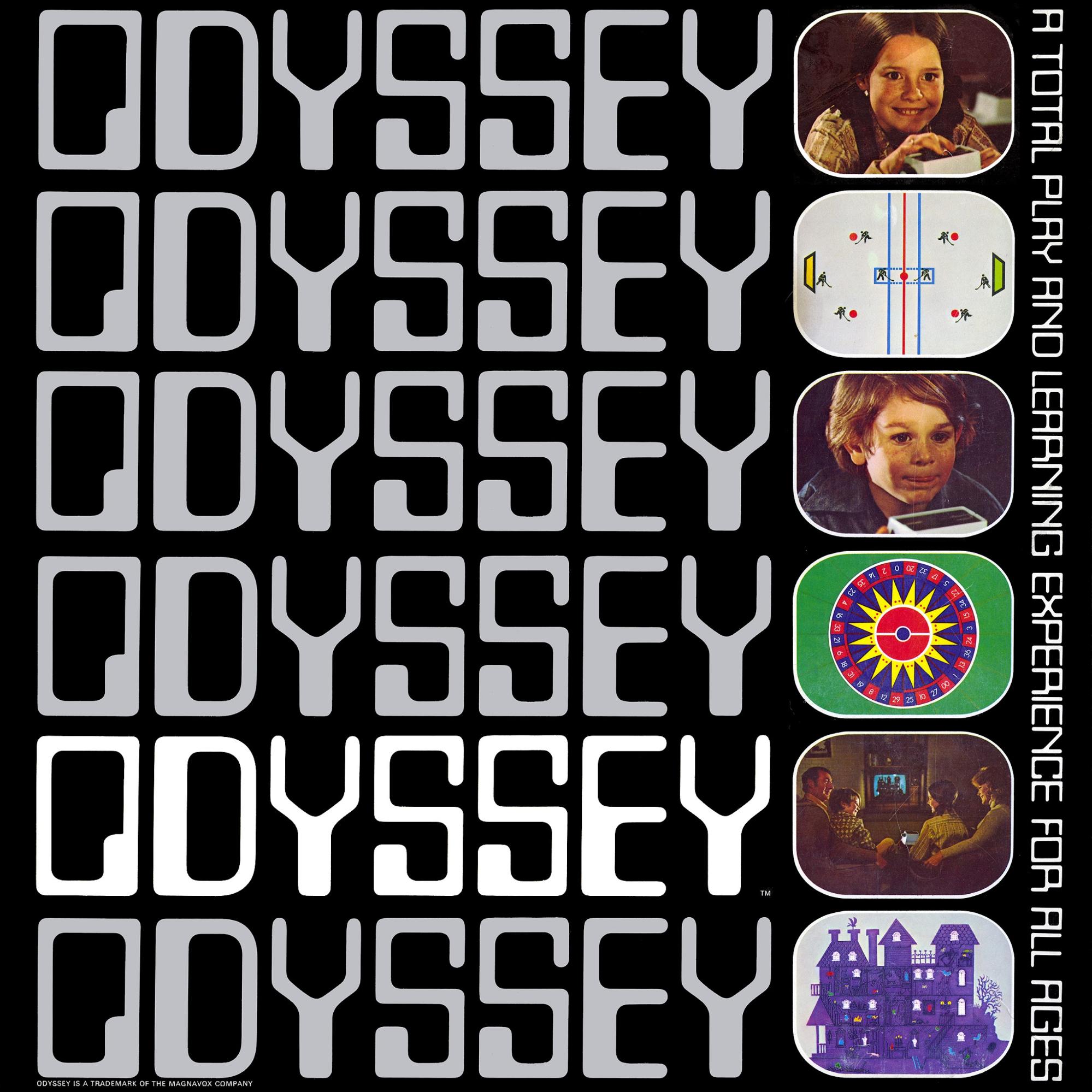

Another question revolves around Odyssey’s box art. The box was most likely finalized after the first commercial was filmed. You might notice that the photographs on the box use the same actors and the same room as the first commercial. It’s very possible these shots were taken the same day the commercial was filmed.

And of course, none of the screenshots are of prototype overlays…except one. Hockey.

Prototype Hockey has fewer players on the playfield, and regular players in the net instead of proper goalies. Normally I would assume this was simply a production error, or that maybe it wasn’t replaced until the very last minute. But prototype Hockey didn’t just appear on the box; it also appeared in the 1973 “Any Brand TV” commercial.

Does this mean the first wave of Odyssey units shipped with prototype Hockey? And if so, when was it replaced? Believe it or not, this one was really easy to answer. Every Odyssey came with an inspection card stamped with a code, and David Winter of Pong-Story.org discovered that part of the code contains the inspection date.

Using this guide, I browsed eBay for any Odyssey listings with a 1972 inspection number and a photo of the Hockey overlay. I was able to find models with inspection numbers as early as August 1972 — which I believe is the earliest known date — and none of them had prototype Hockey.

The next question is how prototype hockey made its way into a commercial from early 1973, when Hockey had been replaced at least as early as August 1972. Maybe prototype Hockey was such a last-minute replacement that there was actually a small, never-released run printed up, and someone in production unknowingly grabbed one of those? Or maybe other copies do exist in the wild, but are so rare that no one’s thought to look for it? Just how much lead time were these commercials given, anyways? All of this we’ll probably never know.

Another big question is whether there were other Odyssey commercials, and how many. ‘70s commercials are so rare that the only circulating copy of the 1976 Atari Pong commercial is so worn out or so many generations old that it’s completely lost it’s color and the garbled audio is barely intelligible. It’s a miracle that we have the 1973 Odyssey commercial, and we wouldn’t have the very first commercial if not for Ralph Baer.

Yet, Ralph Baer mentioned commercials plural. Did he have others? I attempted to contact Video Game Saga to see if maybe they’d been given additional files, but was unsuccessful in reaching them. At any rate, I have to assume they would’ve posted anything they had.

Next, I reached out to aforementioned David Winter, who digitized most of the images in Baer’s Videogames: In The Beginning. Baer’s association with David Winter began in 1998, at a time when Baer was beginning to think about his legacy.

Law firm Leydig, Voit & Mayer had amassed an impressive amount of materials while representing Magnavox in Odyssey lawsuits dating back to the ‘70s, and Baer wanted to make sure the most important items were preserved once the final lawsuit was over. This involved digging through endless boxes at the law firm’s storage facility in Chicago.

According to Baer, his declining health led him to recruit David Winter in 2002 to help locate and catalog these items. In return, Winter was allowed to add much of it to his collection.

Winter confirmed for me that he was the one who digitized the first commercial. He also mentioned he has two copies of a second commercial. He said they appear to be identical and contain an animation effect that, according to his description, sound like rotoscoping or something similar. I was hoping to point my obsessive attention to detail in their direction, but he declined my request to view them, and unfortunately no other sources of this commercial are known to exist.

But at least there’s one more question I can answer:

How does Frank Sinatra fit into all of this?

Ol’ Blue Eyes & The Brown Box

Whether Ralph Baer misremembered or just phrased things in a confusing way, here are the facts:

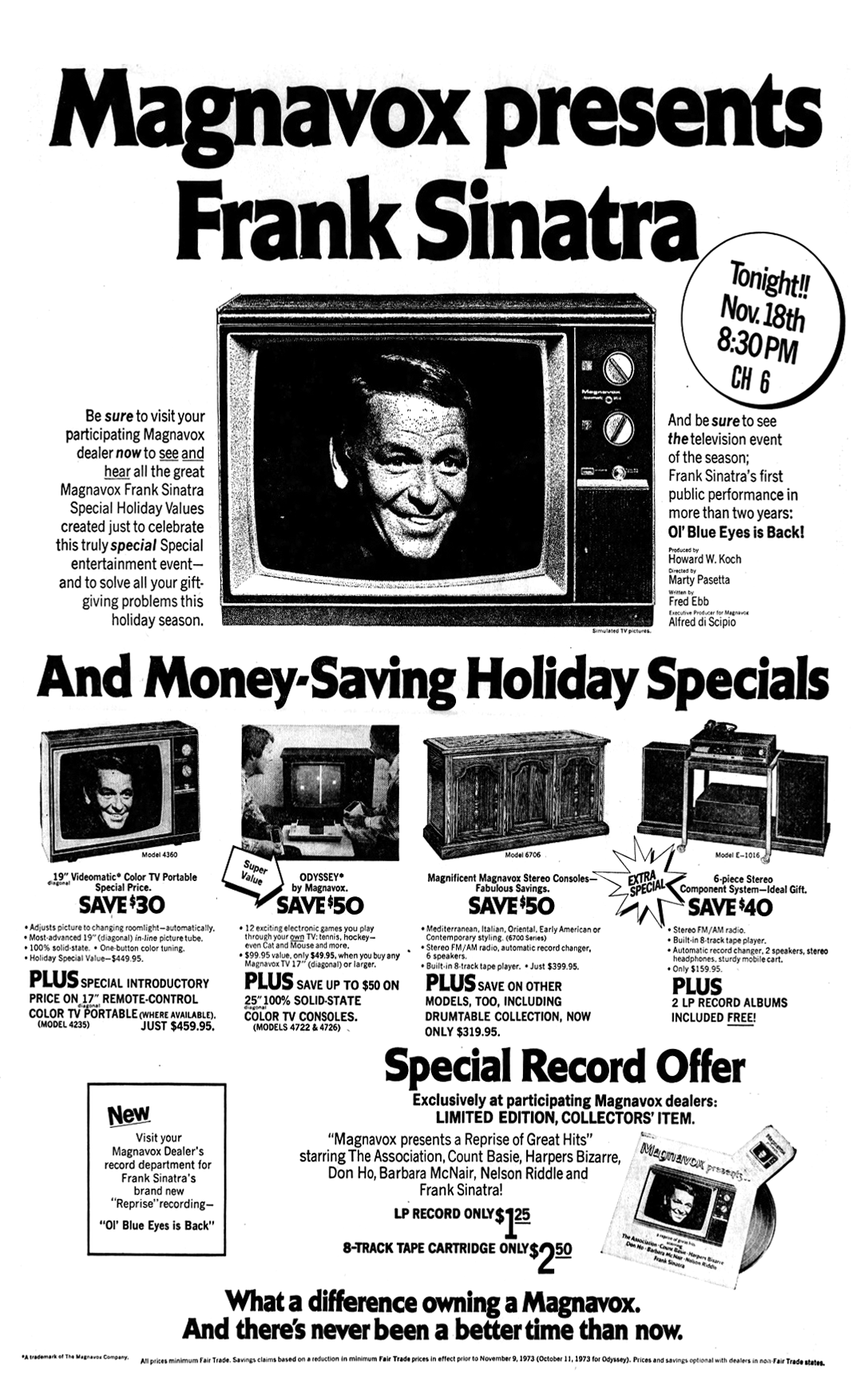

- The “Sinatra commercial” happened during the fall of 1973, not the fall of 1972.

- The focus was on Magnavox’s entire fall ‘73 product line, not just Odyssey.

- The “Sinatra commercial” wasn’t a commercial at all, but an hour-long special sponsored by Magnavox.

Frank Sinatra announced his retirement in 1971, but it was short-lived. To celebrate his newfound unretirement, he recorded a new album called Ol’ Blue Eyes Is Back and did an hour-long TV special sponsored by Magnavox. The special was often referred to as Magnavox Presents Frank Sinatra in TV listings and ads, but when it aired it was suddenly called Ol’ Blue Eyes Is Back to match the album.

As part of an agreement between Reprise Records and Magnavox, ads for the album also mentioned the TV special, and ads for the TV special also mentioned the album. Magnavox used the TV special ads as an opportunity to advertise their fall product line with Sinatra’s face attached.

The TV special itself contained specially made commercials for Magnavox’s fall line, but Sinatra wasn’t the one doing the plugging. The special can be viewed on Youtube, but all the commercials have been removed, and the torrent of the complete show available on a private tracker currently lacks seeders. Thankfully, Youtube channel Flemishdog uploaded the isolated Magnavox segments:

So we end on an anticlimax, but at least we’ve learned a few things along the way. We’ve confirmed the first video game commercial and Frank Sinatra’s lack of involvement in it, plus we’ve gained a better understanding of possible causes of the consumer confusion. Or were we the ones who were confused all along?

Special thanks to Andrew Borman, Chris Chapman, Frank Cifaldi, and Gus Lanzetta.

Follow me on Twitter: @katewillaert.