While working as a barista at a southern California coffee shop, Nina Stanley would serve the same customer every Saturday, without fail.

“This guy would come in at six in the morning with these bags under his eyes, and order an espresso,” said Stanley, in a Skype interview from her home in Albany, New York.

After serving him his espresso, they would chat. They got to know each other. He was a software engineer, she was a fine art student pursuing her master’s degree at California State. He hired her for a small project for his new company.

“He asked me to do this logo, and I painted it in watercolors,” said Stanley.

The end result was a rainbow-hued logo, set against the backdrop of a giant fluffy cloud.

That company? Color Dreams.

That man? Dan Lawton, the founder.

Lawton was pleased with Stanley’s logo, and hired her full-time to design games for Color Dreams in 1989. As a company, Color Dreams was unique in that their games weren’t officially licensed by Nintendo. Lawton, through a technological sleight of hand, bypassed the NES security lockout chip. This enabled Color Dreams to create games without Nintendo’s authorization, which for smaller developers was usually prohibitively expensive.

Stanley was their first design hire, as well as their first female employee. Stanley had the advantage of being a classically trained artist, while joining a rapidly expanding company, producing games for the hottest console in the United States. According to The New York Times, by 1988 Nintendo sold some 10 million NES consoles in the United States. And that, per The Ultimate History Of Video Games, doesn’t include the 8.4 million consoles ordered for Christmas 1988, of which Nintendo could only deliver 7 million. Consumers couldn’t get enough of the NES.

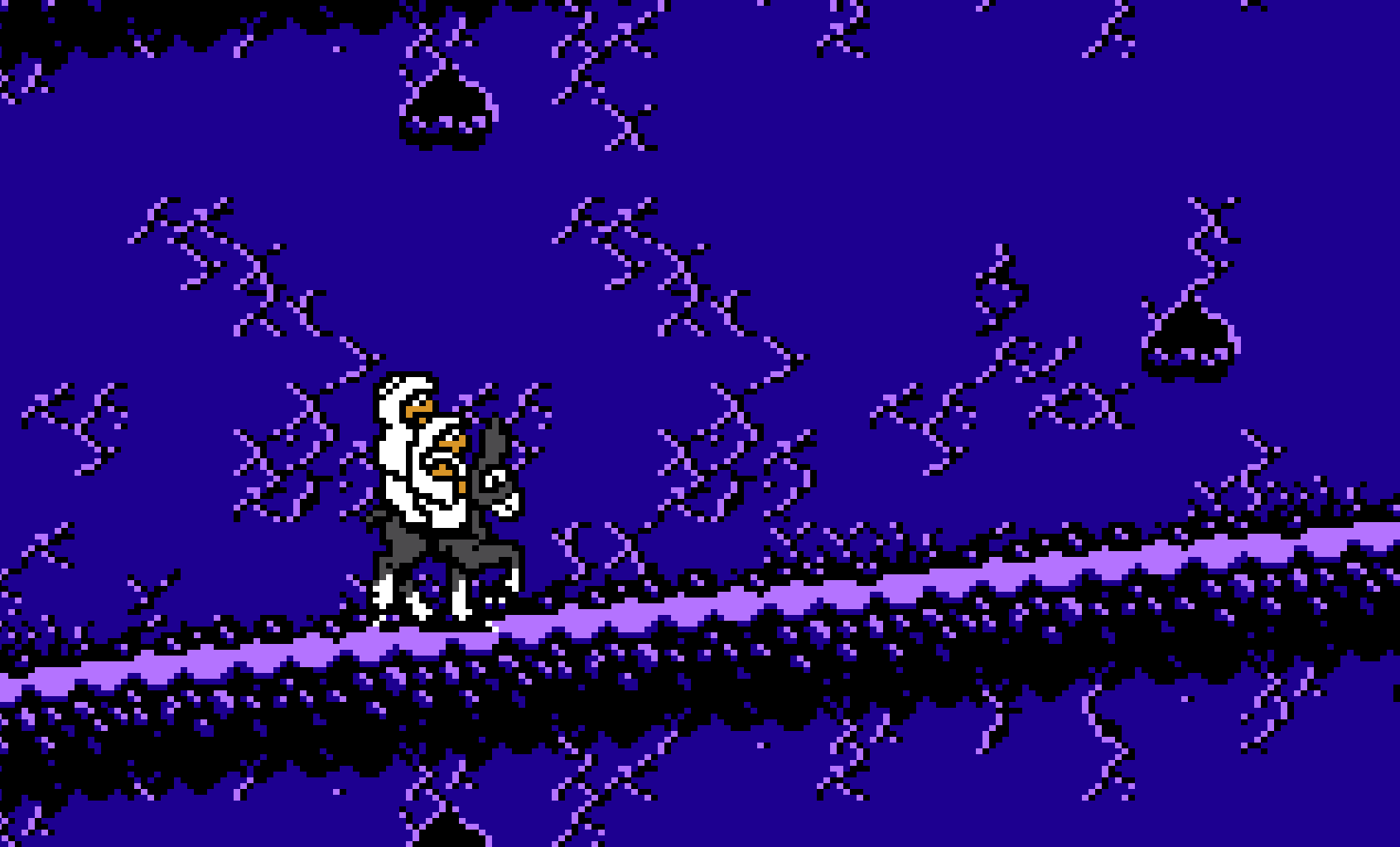

But in this pre-Photoshop era, graphic design technology was clunky and time-consuming. At Color Dreams, Stanley’s work station consisted of a NES console connected to a television. Jammed into the console’s cartridge slot was a printed circuit board, running a rudimentary design program. And instead of a paintbrush, Stanley used the NES controller to create designs in real time, using the system’s limited resolution and colors.

“It was brutal. I would have to use the controller to cycle through colors and place each pixel, one at a time, in little eight by eight squares, to build characters, objects, and landscapes. You had to cycle through all the colors to choose your palettes, and there were four palettes of four colors each, but the first color had to be transparent. If you wanted to use more than three colors, on a part, on a character, you had to be able to blend the palettes across the borders of the eight by eight pixels. So, I did that for a while, and then I said “Nah, this isn’t any fun,” and I went back to the coffee shop.”

But Stanley and Lawton remained friends, and Lawton eventually convinced Stanley to return to Color Dreams with the promise of an updated, easier-to-use design program, the aptly named NinDraw.

“You’d get 256 characters, meaning eight by eight chunks of pixels, eight by eight pixels chunks. There were 256 characters for all of the sprites, and 256 characters for the background for all of the level. And so tiling, and making things, reutilizing the pixels and the artwork to make as much interesting stuff as you could was really a challenge. And I actually enjoyed it,” said Stanley.

Armed with the NinDraw, Stanley went on to produce art for the majority of Color Dreams’ output, which included Menace Beach, whose title page character was modeled after her then-five year old son, Alex.

Soon after, Color Dreams changed its name to Wisdom Tree, and, in a pivot of biblical proportions, began producing Christian-themed games. Stanley stayed on during this era, creating art for games with titles like Bible Adventures, Exodus: Journey to the Promised Land, and Spiritual Warfare. When it comes to her artistic process, Stanley references, among other elements, Jungian philosophy, Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum’s kitsch movement, and classical mythology, which is arguably the central pillar to her approach to games.

Stanley was still pursuing her graduate degree while employed at Color Dreams, and her professor, Don Lagerberg, suggested she incorporate video games into her master’s thesis. The resulting work, “Popular Culture and Myth: Video Games as a Reinterpretation of the Hero’s Journey,” set forth the concept that video games empower individuals through the classic mythology of heroes, and explored how those mythological tropes related to gender.

“I did a ton of research on male and female gender roles, in particular, and how the two [sides] of masculine and feminine myths work through stories, because games are really just storytelling. The female myth is in process, it’s not linear, it’s more amorphic, and it’s really hard to talk about, because it’s connected with the right side of the brain, which is more spatial. And the masculine myth is very straightforward, is very logical, it has the language to describe things with, it’s mathematical.”

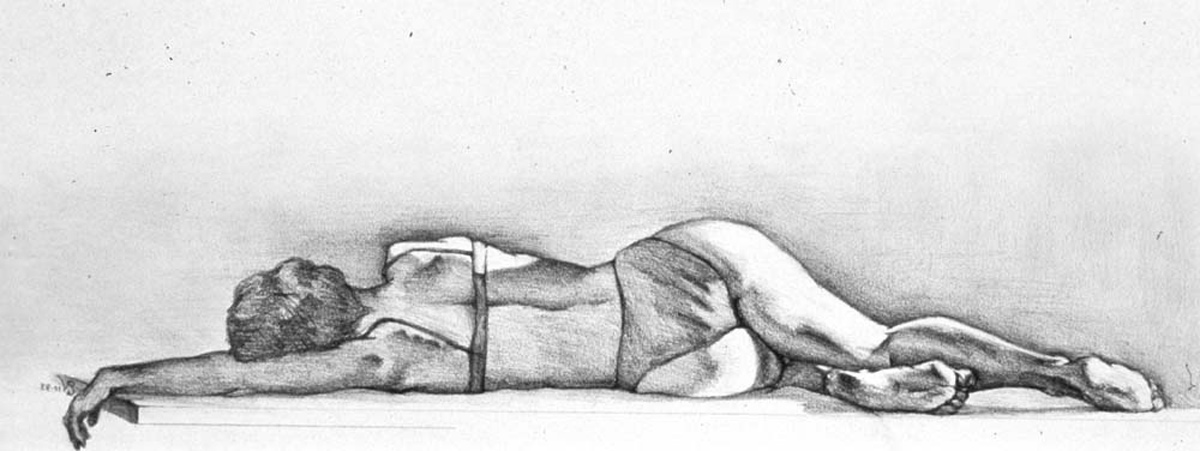

Putting the masculine and feminine mythology of games into artistic practice is, for Stanley, a finely-honed mix between reality and fantasy. She first learned how to draw by creating illustrations for her friends’ “Dungeons & Dragons” characters. As her interest in the medium piqued, Stanley took figure-drawing, illustration, and painting classes while studying for her undergraduate degree, with the intention of marrying her artistic interest with a career that would pay a living wage. Something practical, like graphic design.

“I started out in the graphics department, and I worked in a little print shop, trying to be very practical. I took a life-drawing class, where I learned to draw the human figure, and it was pretty life-changing experience. Because graphic design, while it’s great, you don’t really do a lot of drawing. It’s composition, color theory, and balance, and it’s all stuff you need to know, but I just didn’t want to stop there. I wanted to learn how to draw the figure, too.”

Stanley describes finding her passion for drawing during a period when her father was telling her, in her words, “You can’t be an artist, you’ll starve to death.” Undeterred, Stanley focused her studies on figurative drawing.

“I was able to hook up with the one instructor who was the figurative artist, and I stuck with him all through the rest of my undergrad and graduate degree, and studied the figure, and learned anatomy, and an academic approach to art. Not academic like our school system, but academic like The Academy, where you learned to draw from observation and real experience. It’s an art that was kind of pushed aside with the pop era, and the modernist movement, where they stopped putting an emphasis on the figure. I think what happened, and what’s happening now, is that those of us that pursued the realistic and more academic style of work went into the entertainment industry.”

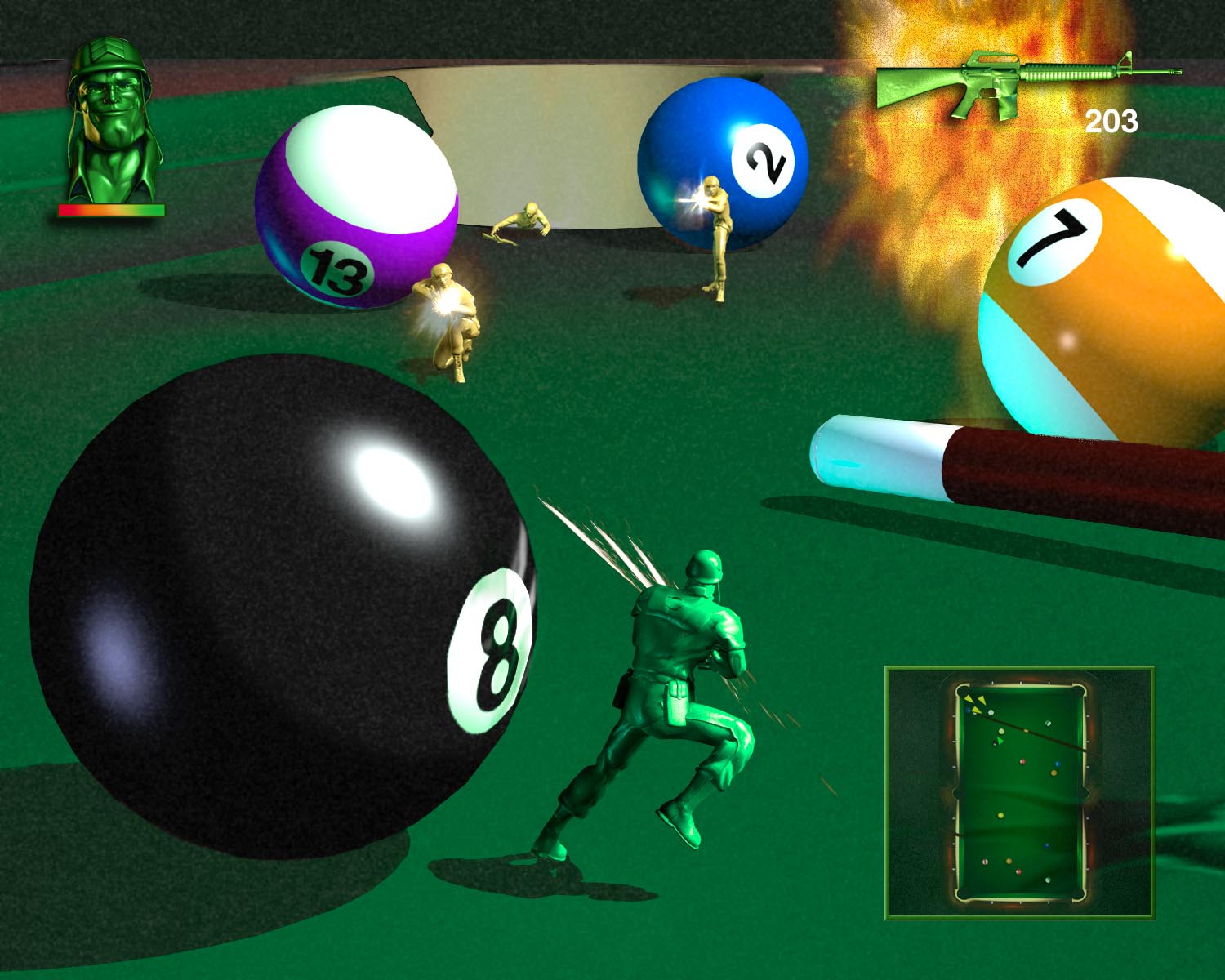

The entertainment industry, by way of games, is certainly where Stanley found her niche. After leaving Color Dreams in 1992, Stanley worked for several industry titans of the decade, including Capcom, Electronic Arts, and 3DO, as well as smaller developers like Vicarious Visions. Stanley believes she produced her best design work at 3DO, for the BattleTanx and Army Men franchises. As art director for Army Men: Sarge’s Heroes, Stanley implemented a host of techniques which defined the game’s signature look and feel. Most character designs started as photo references or live model drawings.

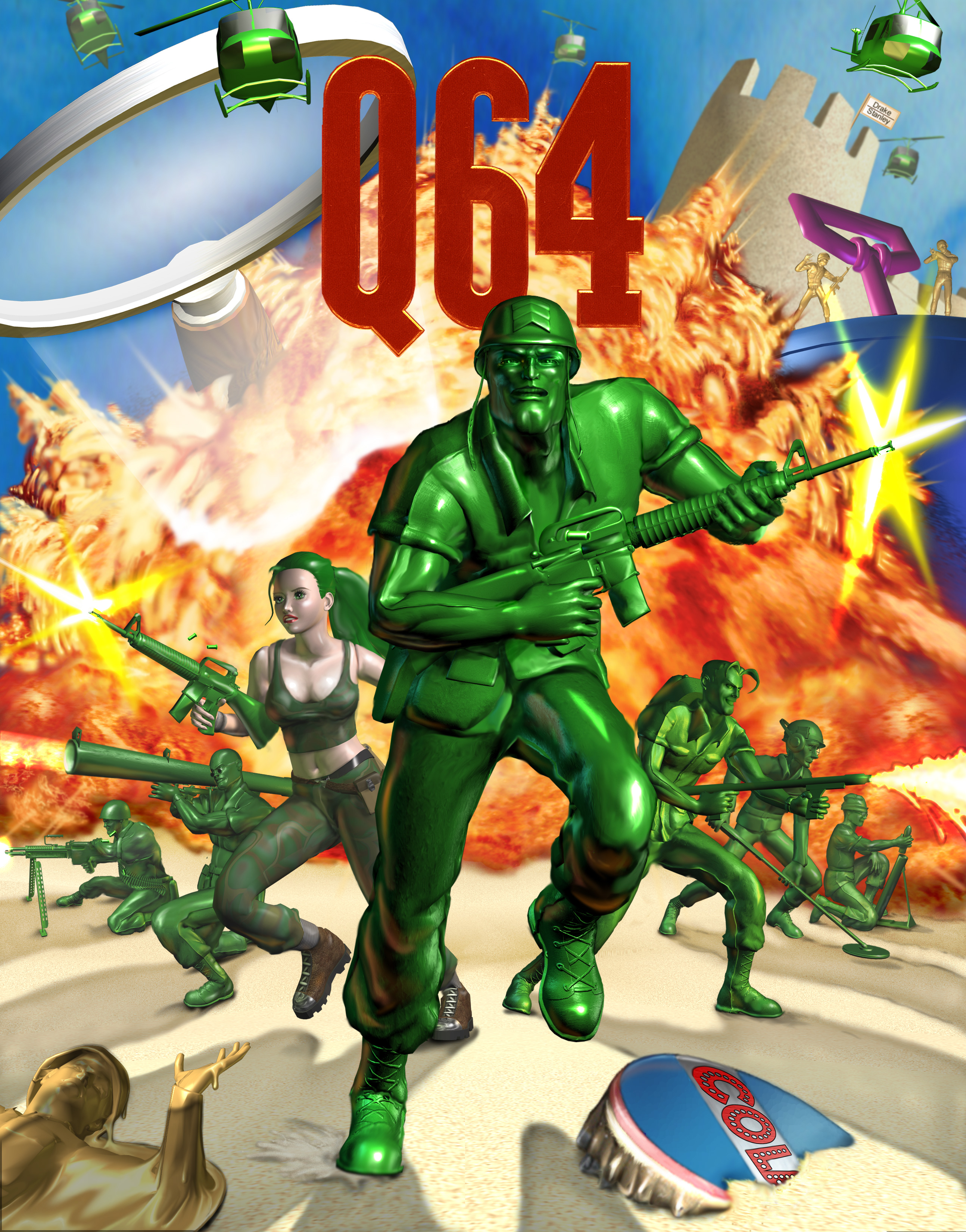

For marketing projects, like the magazine cover below, Stanley would take the 3D-rendered characters and paint over them, to reduce their polygonal appearance and provide greater detail. The same process would be applied to other background and foreground elements, like artillery and explosions. Photoshop would be used to stitch the scene together, to make the scene appear as a cohesive painting.

Upon further reflection, Stanley appreciates her accomplishments in those early Color Dreams days, too. “I’m actually pretty proud of some of the 8-bit art that I did. I was able to put Mary, Joseph, and Jesus on a donkey in 24 by 64 pixels. How do you make a baby Jesus out of four pixels?…I still crack up when I see that stuff, because it’s so small. Believe it or not, the training I have in making things look real, which is an optical illusion, makes things more interesting. And when you let the mind fill in a little bit, you can make it seem more realistic.”

Stanley’s video game career spanned 15 years with over 25 credits, including Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 4, Batman Begins, Spider-Man 2, and several Disney titles, and most often for portable versions on the Nintendo DS, the Game Boy Advance, and the PSP. She was usually the lead artist or art director on each project, and more often than not, the only woman.

“It seemed normal to me. I don’t know why. I felt comfortable with guys. Most of my friends were guys. Girls tended to be mean. You know, when you’re playing chess, what’s the most powerful piece on the board? The queen.”

But while Stanley worked for Electronic Arts, it was fellow female artist Laura Bowen who created the Road Rash 3 character drawn in her likeness. As Stanley tells it, “[Laura] arranged to take pictures of a bunch of us in the development group, and I was into biking and Russia at the time, so it worked out well. Plus my name is traditionally Russian. I show up in Level 2 as a NPC Rasher with some funny quips when the player screws up.”

Above all, she attributes her ability to thrive in the games industry on not just being friends with her male colleagues, but by her active enjoyment of shared activities like paintball, or playing Doom on a LAN.

“Most of the women that came into the game industry in the early years, if they wanted to make games, they were tomboys. They were really more masculine-ish, if you could say. They liked to play sports, they were more logical, they didn’t want to play house, they wanted to play battlestar battles with men. And I was a tomboy too, racing go-karts up and down the alley and things like that. It has taken a long, long time before we’ve gotten into a place where there is more crossing of the gender lines, and of course that’s the cash cow, right? If you can make a game that appeals across gender and age, you’ve got a blockbuster.”

Currently a professor for the Art Institute of Pittsburgh, Stanley teaches game art and design to a generation with access to advanced software and animation solutions, a far cry from her primitive NinDraw days. (Or when she taught herself 3D design in DOS.) She is, however, decidedly not a fan of using design software without understanding the fundamentals of drawing and anatomy.

“When I teach now, I teach the principle that if you draw from reality, and you want to make something look real, then you better understand what makes it look real. You need to draw from real things, like plaster casts, still life setups, real human beings–not photographs, but real human beings–if you’re going to stick wings on a dragon to make it fly, you better understand how that works biomechanically,” said Stanley.

“It’s the whole reason I became an artist,” she continued. “I stumbled across the secret code on how to make something look real. If you love what you do, you’ll do more of it. The more you do it, the better you get. The better you get, the more you like it. Picasso already knew all the fundamentals, so he was free to move on and experiment. He already knew how to make a cake, so then he could make a really amazing cake. And he could do what had never been done before.”