We were fortunate enough to have a space at GDC 2017’s first-ever Retro Play area, alongside a handful of other organizations. We had three main goals with our display:

- Promote our “We want your old development stuff!” campaign, which encouraged game developers to archive their old materials so that historians of the future can tell our stories.

- Display games that have a preservation story – that is, games that are only accessible because archivists went out and found them.

- Inspire game developers to find new ideas in old materials. I’ve been going to GDC every year since 2004, and even worked for the company for a time, so I wanted to make sure we weren’t just another “retro” display – I wanted us to fit into the GDC ecosystem.

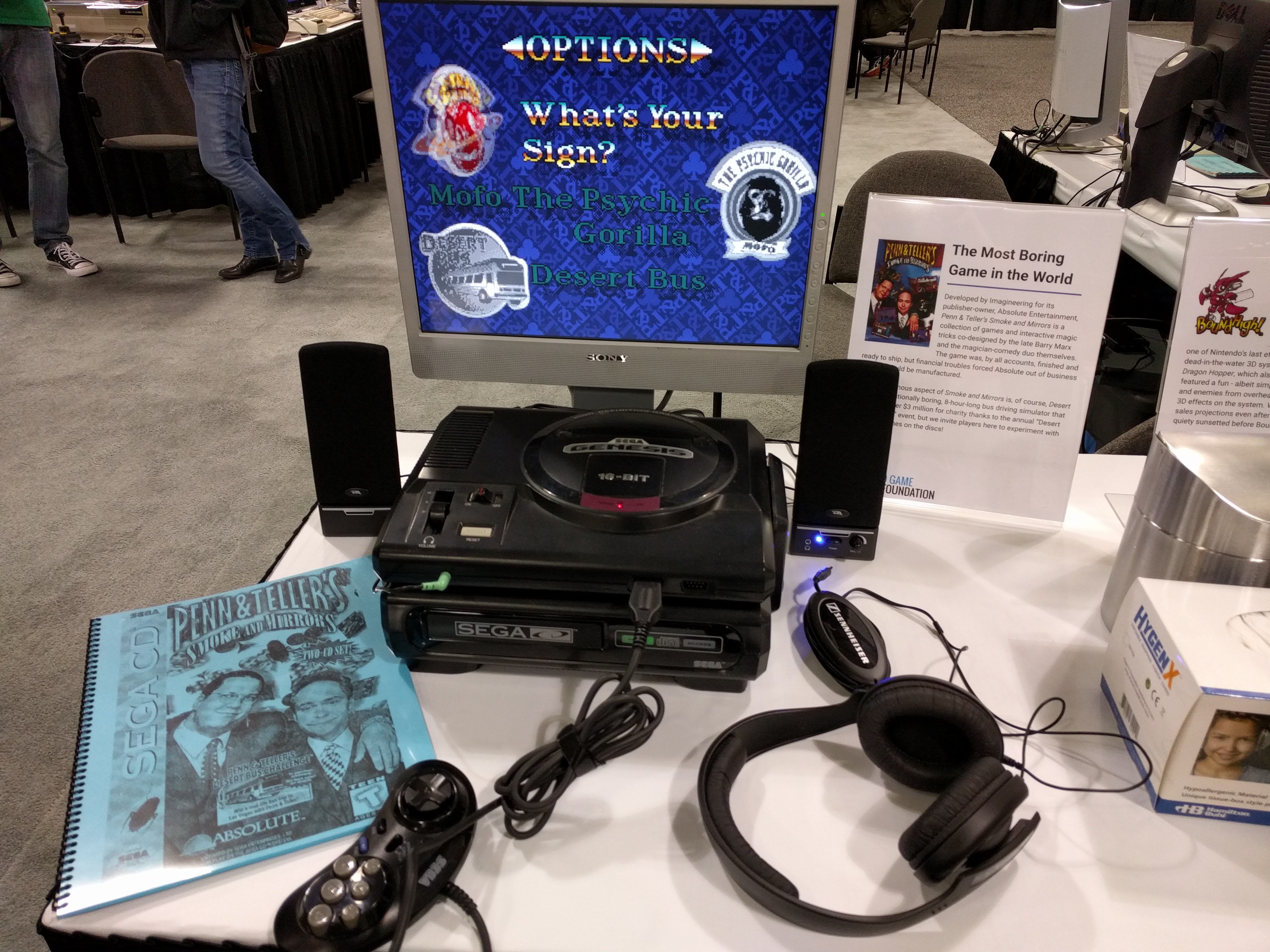

This is Penn & Teller’s Smoke and Mirrors, an unpublished game collection by Absolute Entertainment. The game wasn’t cancelled for quality reasons – rather, it was completed and ready to ship, but fell victim to Absolute itself going out of business.

We think this game is a particularly interesting artifact, as it’s an example of outside influencers with no video game industry experience (in this case, comedy-magician duo Penn & Teller) directly impacting design. The result here is a game that, while flawed, is full of wild ideas that may not have ever come from a traditional game designer. “Desert Bus,” an intentionally boring game that requires the player to drive in a straight line for over eight hours, is probably the most famous example.

We thought this would be a good opportunity for show-goers to explore the rest of the game’s offerings, so we printed out the manual, which is absolutely necessary for content like “Mofo The Psychic Gorilla,” a virtual magic trick involving secret button combinations and audience participation. Unfortunately games this complex don’t work well for a show environment, so we might have to retire this one if we ever repeat the display.

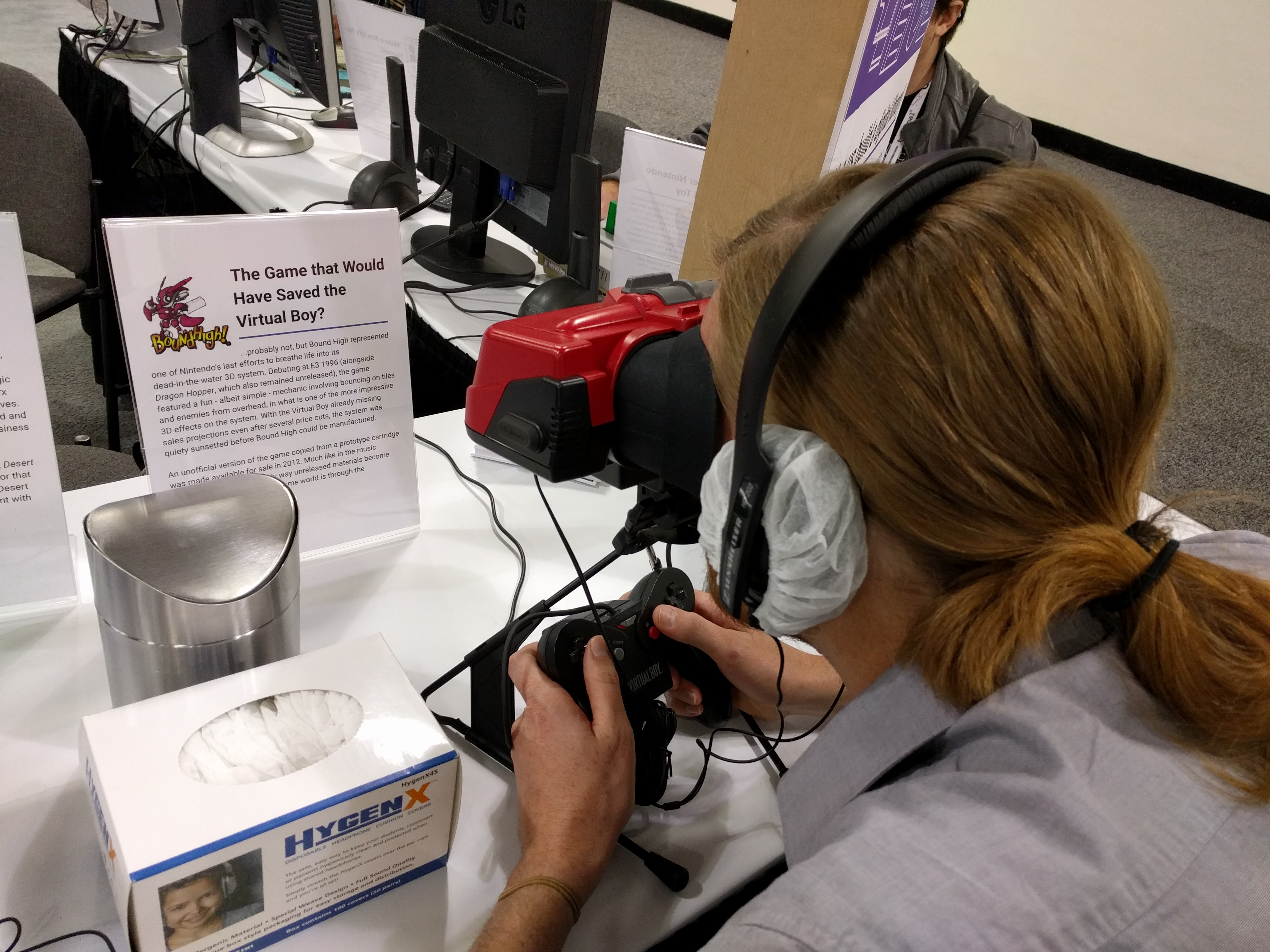

This is Nintendo’s Bound High for the Virtual Boy, another unpublished title. Like Smoke and Mirrors, quality concerns likely had little to do with the game’s cancellation – rather, the Virtual Boy itself had been all but phased out by the time the game was ready for manufacturing.

Also present in this picture is an idea we were fond of that didn’t catch on – we wanted players to have the option of using headphones to engross themselves in the games, but we also wanted to do our part to prevent the spread of germs at the show by offering hygienic headphone covers (and a tiny receptacle to dispose of the used ones). Unfortunately, not one attendee caught on without us prompting them – they either ignored the headphones entirely or put them on without the covers. By day two we quietly hid those materials away, to give our display signs better placement.

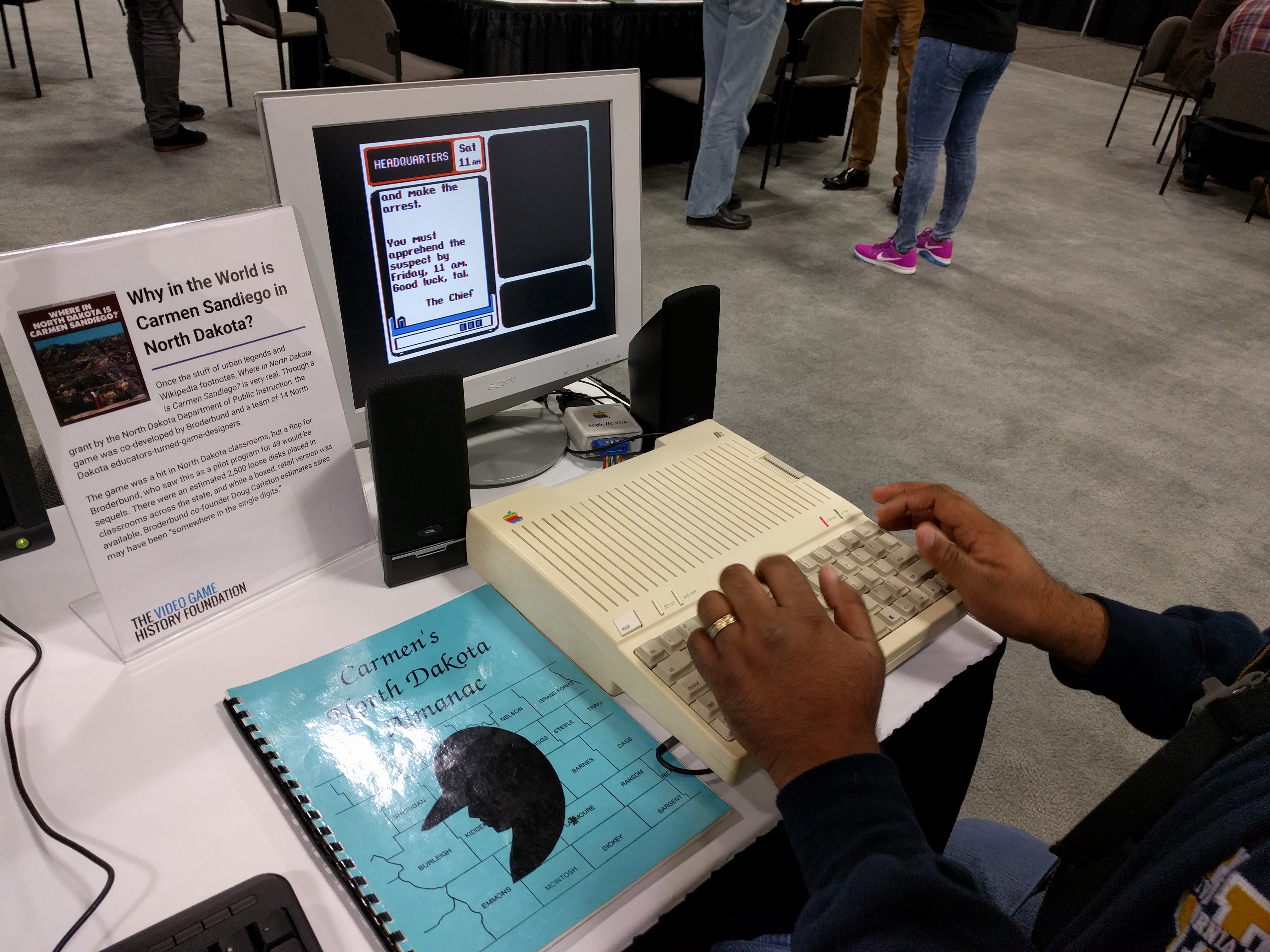

This is Where in North Dakota is Carmen Sandiego?, a sort of pilot program by Broderbund to see if it could make region-specific Carmen Sandiego games financially viable. “Carmen ND” is the subject of an upcoming digital archive that we will be adding to our digital library in the very near future – we traveled to the state last year to meet the teachers involved in the project, and came back with some incredible material, including photographs and internal documentation from the making of the game.

“Carmen’s North Dakota Almanac,” as seen in this photograph, was one such artifact. The prior two Carmen games (“World” and “USA”) both came with almanacs in the package to help players solve the game’s riddles. There was no North Dakota almanac to include with this game, so the teacher’s made one! This was the only true artifact we brought to the show, rather than a recreation. We figured if this thing could survive for years in a 4th grade classroom, it would do okay at a three-day expo (plus, we have multiple examples in the archive).

The game was a big hit, in terms of a fun story to tell, but Carmen games aren’t exactly show-friendly. That said, we applaud the four brave Acme agents who sat down and actually tried to solve a case. Sadly, no crooks were caught during the entire show – even with the almanac, this is a very challenging game.

The biggest hit at the show was Sound Fantasy, an unpublished, mouse-driven “music toy” by Nintendo for the Super NES. The game was designed by Toshio Iwai, and its influence on his later titles (including SimTunes and Electroplankton) are immediately evident.

The “Beat Hopper” game included was particularly addictive to show-goers. The game takes a little over twenty minutes to complete, and we had no less than three players go through the entire game!

Unfortunately, the build we have access to – still under its working title of Sound Factory – is incomplete. We have high hopes of one day accessing the final game, which we understand was completed, and has been demonstrated in the past.

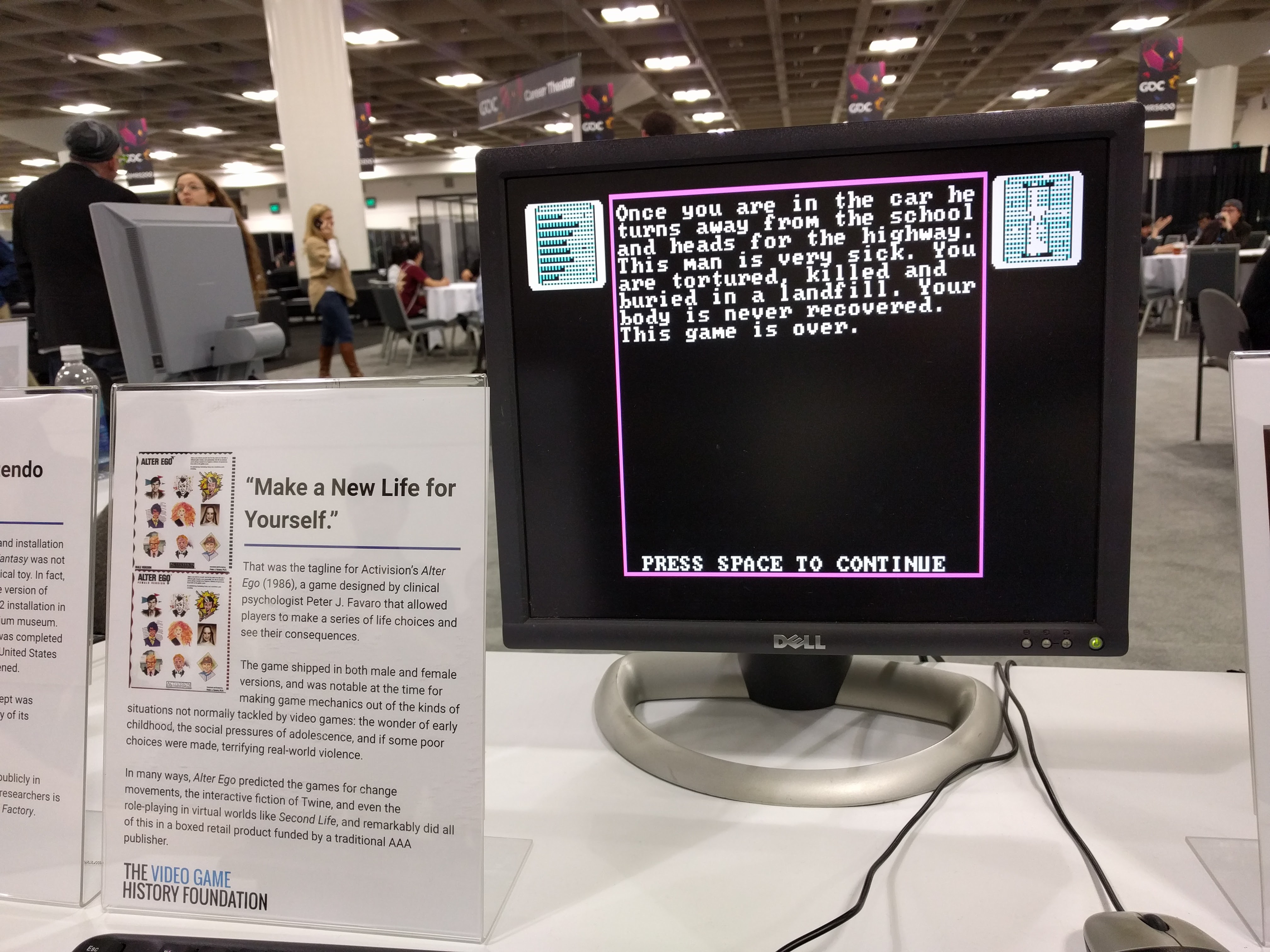

Unlike the rest of our showing, Activision’s Alter Ego doesn’t have much of a preservation story. The game was shipped at retail, sold reasonably well, and is fondly remembered. However, we felt that the game could be influential to modern game developers, especially those who work on text-heavy, narrative experiences. The writing in this game is wonderfully evocative, and the stories that players take away from this introspective work tend to stick.

We only had three people actually sit down and play Alter Ego, but all three of them were really excited. We’d call that a win.