When researching video game history, a lot of wonderful information is just a Google search away. But if you want to dig any deeper, it can be difficult to find information which is not widely disseminated.

Google’s default search is tailored toward finding the most relevant searches for the widest array of people, and most people don’t need to trawl through 40-year-old newspaper articles on Pong to find what they’re looking for. But what about for us, the dedicated?

Luckily, there are some great online databases of web and print holdings out there. These will help get closer to the actual source of any given story, which is important for researchers. Stories have a peculiar habit of morphing and changing as time goes on, and the closer we can get to the source of the story, the closer we can get to the truth.

To accomplish this, we’ll be hoping to sort these database search results into chronological order. Doing this will help us find the root of certain stories, or the first mention of games, which in themselves could lead to the discovery of other relevant texts.

The Basics

Let’s first talk about search terms generally and how they can be used to access information. Most modern search tools allow for specific phrases to be searched independently of other words, rather than lump everything together. For instance, if you type “Super Mario Bros” into Google without quotes, you will get results for every single Google-listed webpage that includes the words “Super”, “Mario”, or “Bros” on any page. The relevance function helps these get sorted together for larger topics like this, but for more obscure information you need specificity.

Searching for an exact phrase is as simple as putting it in quotes, Google Search: “Super Mario Bros”. However this by nature excludes anything which doesn’t contain this exact phrase, so any results for “Super Mario” by itself or “Super Mario Brothers” will not appear. You can hybridize the search by separating “Super Mario” into quotes and “Bros” outside of that, giving all results for “Super Mario” and using the “Bros” term as an additive. Phrases not in quotes will substitute for other common spellings when possible.

One last note is that some ‘search in document’ functions operate by page rather than by the whole document. For instance if you have “Super Mario” on one page and then the next page starts with “Bros”, sometimes an in-document search will not recognize it as a single string. Likewise, if a phrase continues to another paragraph “Super Mar- io Bros” the dash will sometimes be counted as a character. This is why it’s best to have shorter search terms and to look for sources with good OCR.

Aside: What is OCR?

OCR (Optical Character Recognition) essentially means that a scanned document is text-searchable. PDFs are the most popular format for OCR, but others like CBM also have a text search function built-in.

Most files need to be converted to OCR in order to read the text, and without hand modification, these text readings can sometimes be inaccurate. It’s a trade-off of speed versus accuracy.

Both Adobe Acrobat and Archive.org have very serviceable OCR functions, but it also depends on the resolution of each individual page – the better then scan, the more likely the OCR software is to “see” the text. Even if a piece has been OCR’d, if it had a lower page resolution or non-standard formatting it may be worthwhile to read the entire text yourself.

Chapter One: The Internet Archive

The Internet Archive holds the largest collection of freely-accessible publications and resources in the world at present. Through the efforts of independent contributors, institutions, and staff uploading resources, there is a wealth of knowledge to comb through here.

Note: If you, like me, are interested in contributing material, video game-related or otherwise, to Archive.org you can sign up for an account or visit the textfiles Discord maintained by major staff member Jason Scott. The process is fairly straightforward, and text-related documents will be made searchable automatically.

Archive has a relatively sophisticated search function which allows for very easily separated sorting groups. However, there are a few quirks which need to be understood when dealing with their system, which we’ll get into as we go.

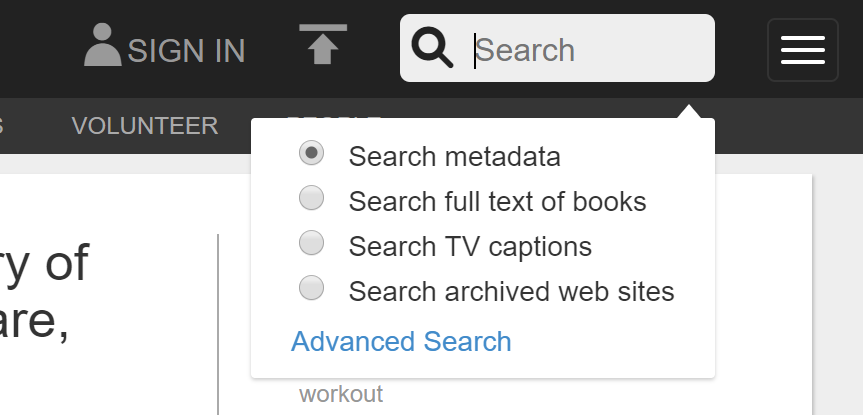

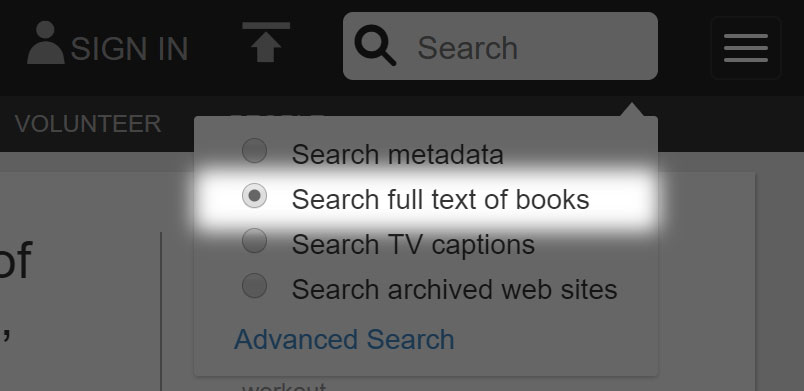

Our first task will be to find the earliest mention available for the original Super Mario Bros. in a trade magazine. To start, we will go to the search function and select “Search full text of books” to set the search into ‘reading’ mode.

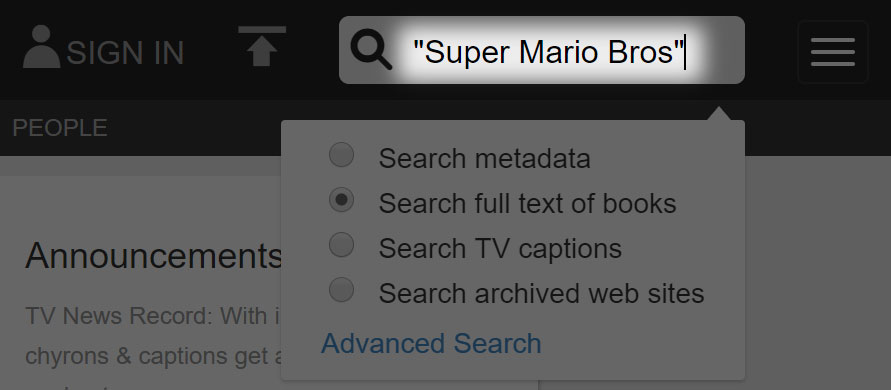

The next step is to type “Super Mario Bros” in quotes into the search field. Remember, this will only get us this exact phrase, but it will work for our purposes.

Note: Placing the period at the end of “Super Mario Bros.” will not affect search terms because punctuation are treated like a space. This is important if you are searching for something like “I.Q Computer” which requires a gap between the “I” and the “Q”. Double spaces are consolidated to a single space.

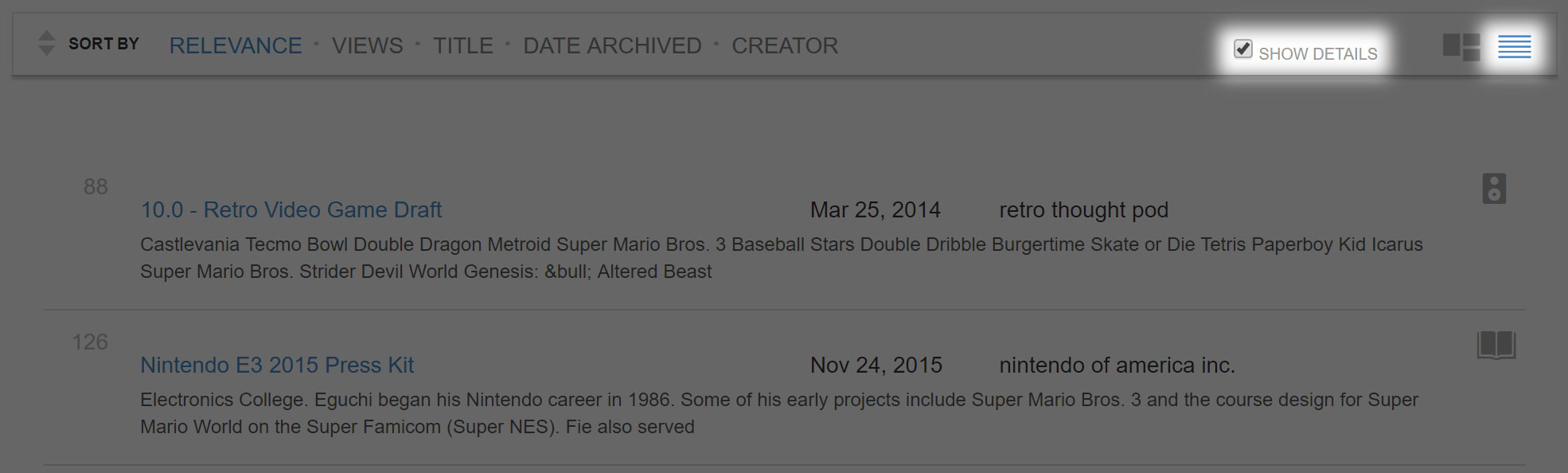

Once we hit the search button, we will be given a list of resources. The most useful search set-up for our purposes will be “Show as List” and “Show Details” selected, shown above.

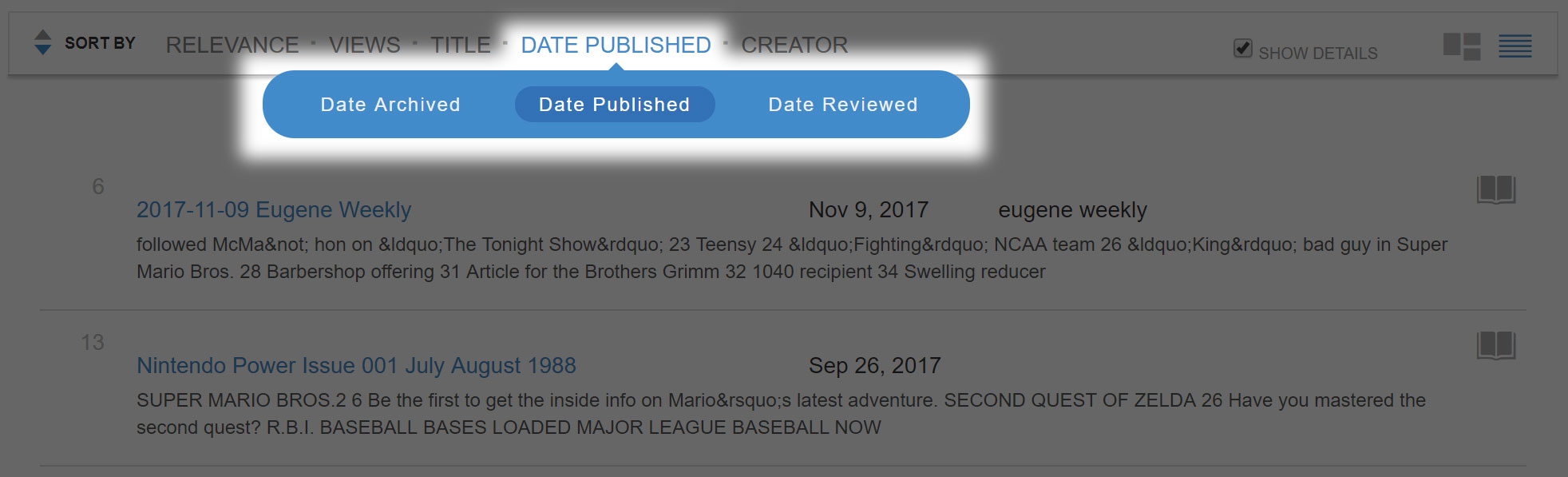

The default sorting order is by “Relevance” as indicated at the top bar. To switch to a chronological sequence, hover over the fourth option at the top bar, go to the drop down menu, and select “Date Published”.

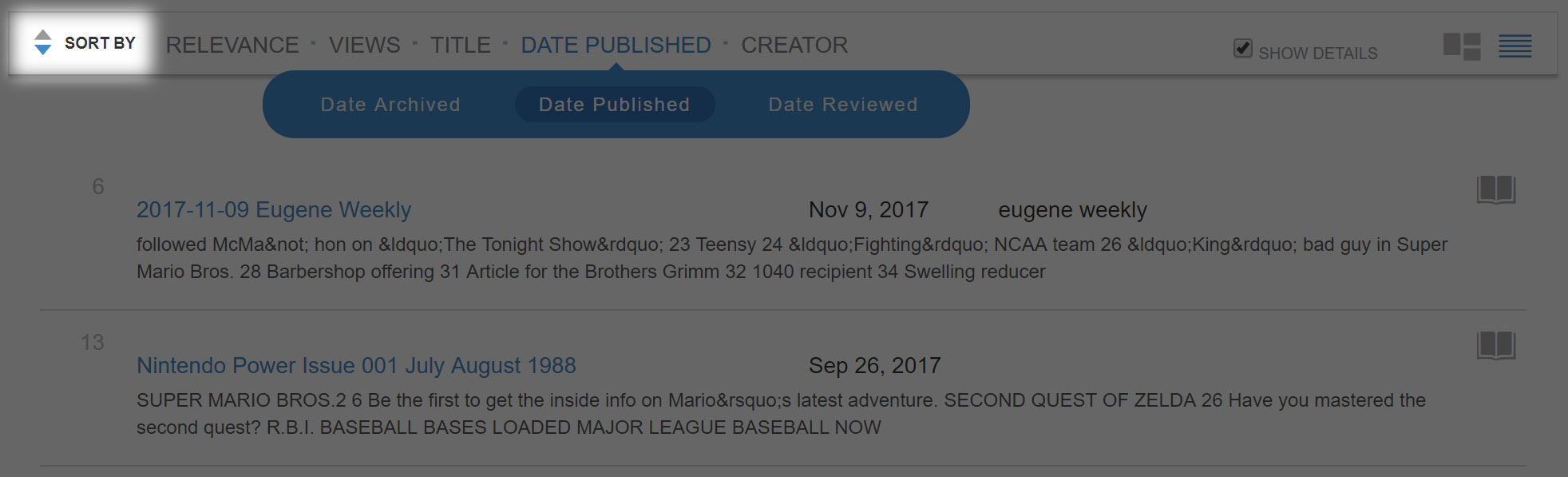

The list is currently sorted in reverse-chronological order, which is useful in some cases, but not in this particular exercise. For now, we will sort this oldest to newest by selecting the set of arrows in the top bar so that when the page refreshes the top arrow will be highlighted.

Note: Items without any publishing date in metadata will always appear at the bottom of the list regardless of their sorted order. These are useful to check to see if they fit in your timeframe, but you will have to visit each individual page to determine if that’s the case.

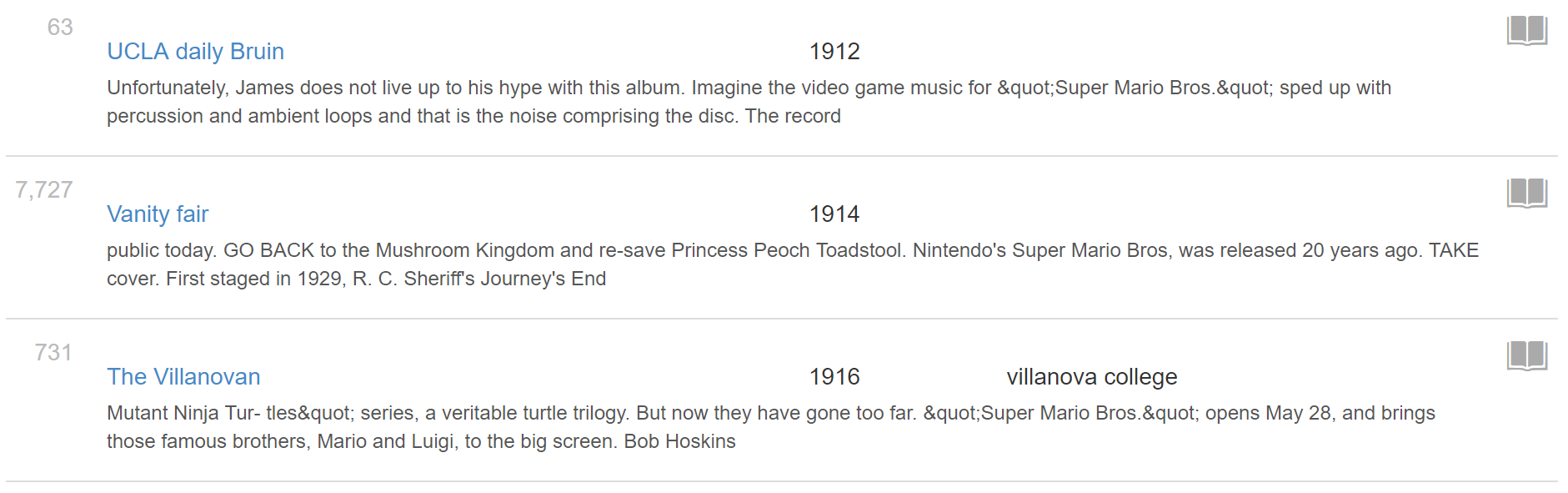

The first results will perplex anybody who knows about Super Mario Bros., with listings in the early 1900s for a game that didn’t exist until 1985. This is one of the eccentricities about Archive.org. If a specific item or issue is not provided with a single date, it will acquire the date of the earliest issue of that publication, in this case UCLA Daily Bruin in 1912. These pages may still hold interesting information on Super Mario Bros., but you will have to go to the page proper and discover what the actual date is (and if you are so inclined, you can flag the item for “Broken or Empty Data” to help get it fixed).

Let’s scroll down until we reach near the bottom of the page.

Aha! Two entries from 1986. Now we’re on the right track. The first entry comes from the copyright date on the manual for VS. Super Mario Bros. (the arcade version), but the second leads to the publication Cash Box, a music trade magazine with a section on coin-operated arcade games in each issue.

Note: The order for all dated documents will proceed in Year, then Month, then Date. I.E 1986 will come before February 1986 which will come before February 15, 1986.

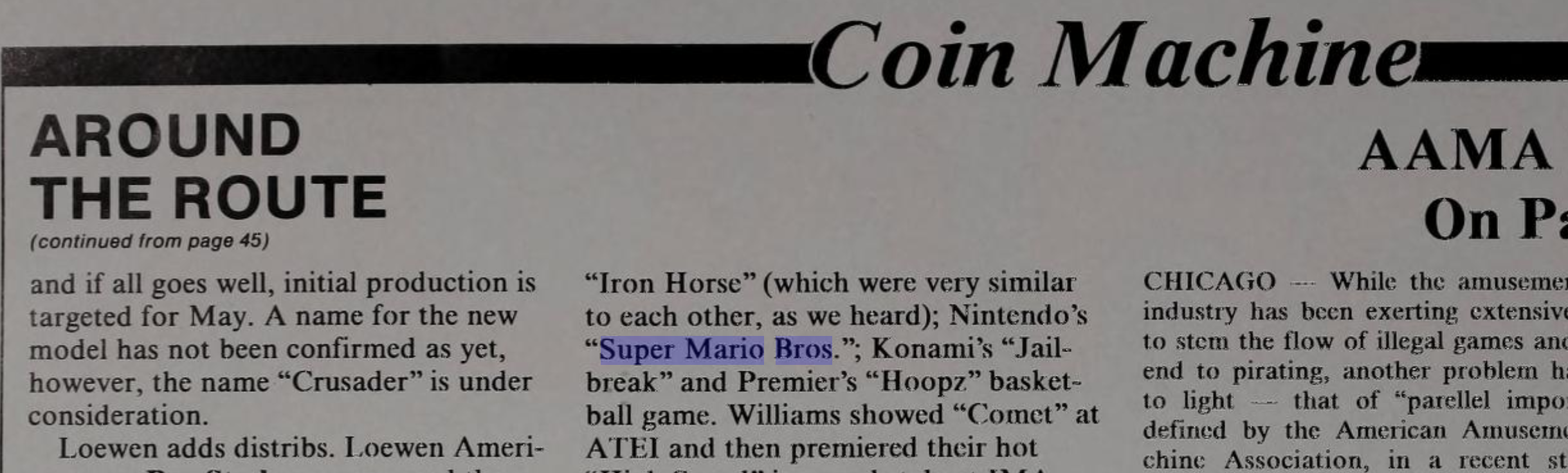

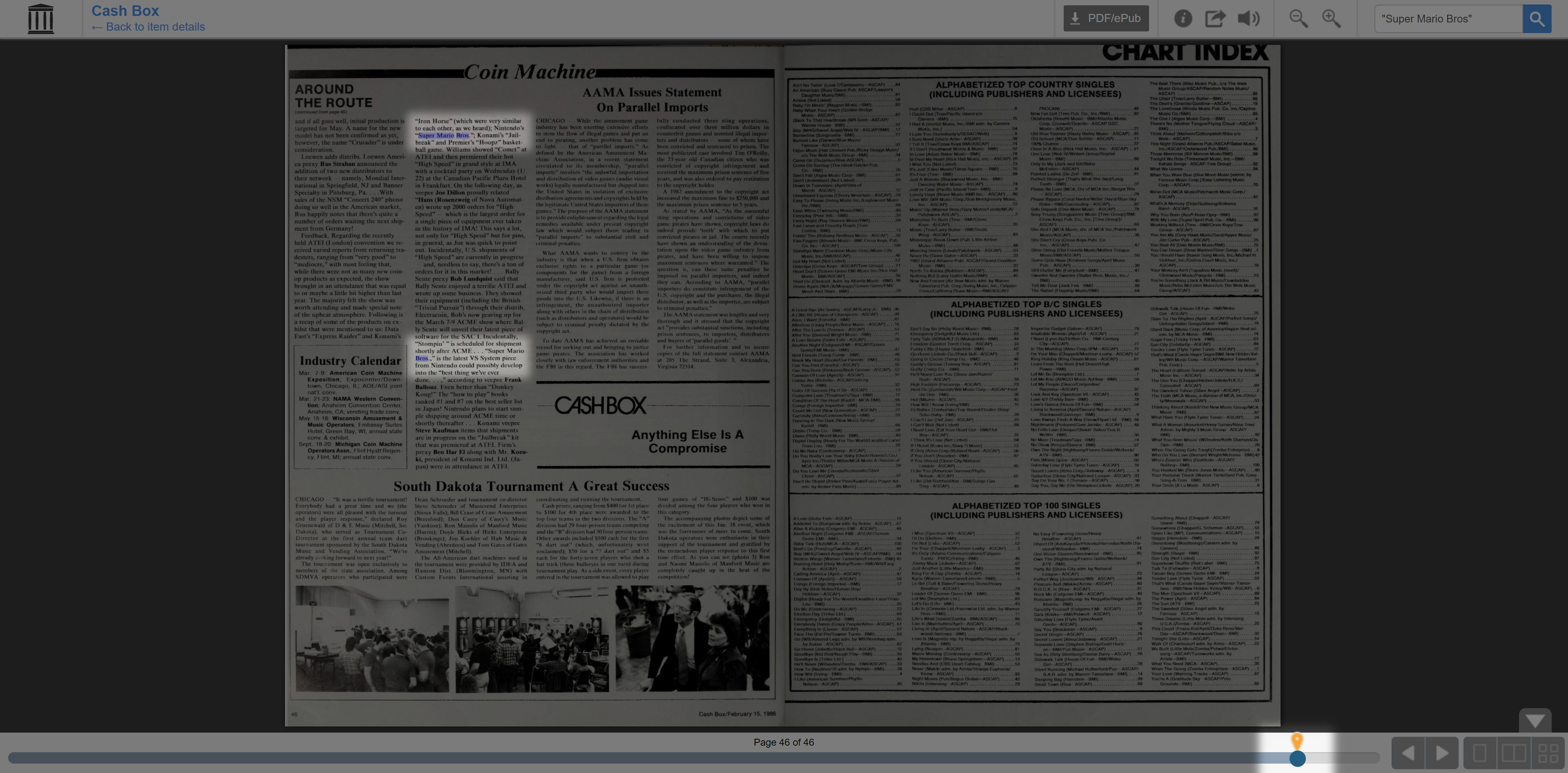

When you visit a page from a search command, Archive will automatically do a search for the first mention of the search term in the document and highlight it. To get a larger view of the publication, click the magnifying glass icon (or the full screen icon if the magnifying glass does not appear).

Note: If a search term does not succeed in the document itself, you can double check by going to the “Full Text” option at the right of the page and using your browser’s built in “Find on Page” function. It’s important to note that within the document itself, the Internet Archive ignores paragraph spacing, which will not be the case on the “Full Text” page. Try searching the key operative words like “Mario” instead of the full phrase.

Upon entering the document, the term will be searched again and all instances of that exact search term will be found, both highlighted on the page and denoted by a yellow marker on the bottom search function. In this case, there are two search results on the same page, page 46. The second result is separated by a paragraph so only one word is highlighted (there can be some issues occasionally), but it has found the exact character string in two places.

Bonus: A lot of captures from Archive.org use the low resolution version available from the full zoom out. If you want a high quality image, use the zoom function to get as close as possible to the page. From there you can “Save Image As” and get the highest resolution version of the page available on Archive.org. This is particularly useful for retrieving rare art from a scan, such as a vintage photograph.

Let’s go back to our initial search and scroll down until we load the second set of results.

Once the second page loads, you will notice that the appendage “&page=2” has been added to your URL. If you refresh this page, the page will be loaded with results starting at page 2 with no way to scroll back up to page 1. Good etiquette when searching on Archive.org is to open pages in a separate tab so as not to lose your place. If you ever do need to return to the first page of results, or jump forward to any page, you can do so by removing or modifying the “&page=2” suffix respectively.

Also recommended, since it can be needlessly time-consuming to start a chronological Archive search, is to bookmark the page one url. With this URL you can substitute in any search term between “query=” and “&sin” where “Super+Mario+Bros” currently lies. We will go into this more in the next section, but remember that searching within quotations will search for an exact sequential string of words. The plus signs “+” can also be substituted with spaces “ “ which will appear as “%20” per their hexcode.

Now let’s try a different type of search and a different type of document. We’re going to try and learn more about 90’s virtual reality, specifically the company Virtuality in Britain. In the URL section we just mentioned, let’s put the term “video game” in quotes, then a space, then followed by “Virtuality” not in quotes (though on the latter it really doesn’t matter).

By specifying “video game” before “Virtuality”, we will likely eliminate results which have the same name but are not related to what we’re looking for. There is still a bit of that ambiguity which can be weeded out with better search terms, but one has to experiment and read related articles to find the proper wording.

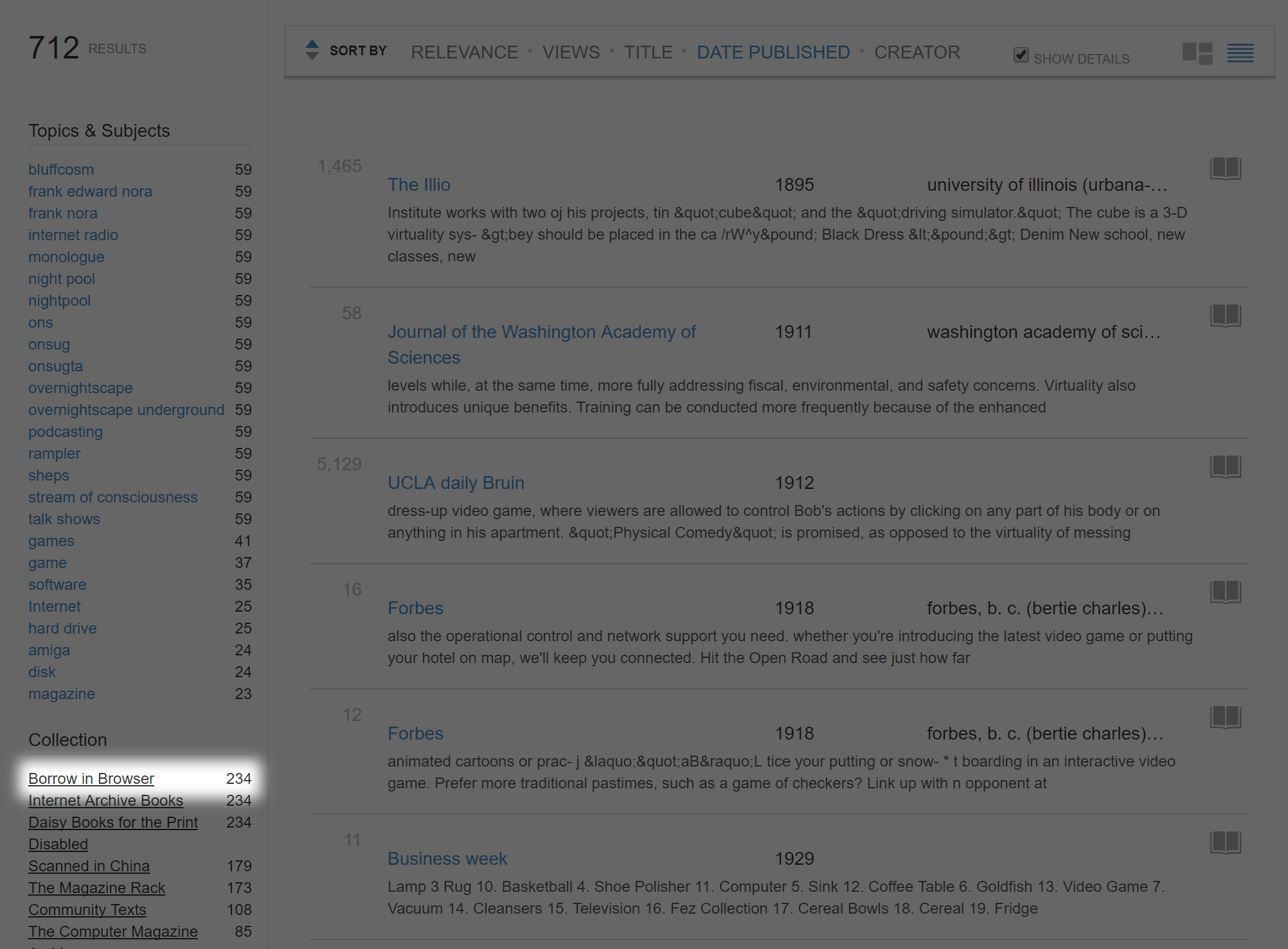

This time we’ll be searching for a particular type of publication. On the left side of the screen there is a robust tag system which can help narrow down searches, and under “Collection” we’re going to click on “Borrow in Browser”.

Note: The tag functions can be useful in narrow search queries, but will also eliminate potential candidates which do not contain tags. You should only use these functions if you have a specific publication or type of publication in mind. Here’s a link I use for searching the publication Cash Box with “Nintendo” as the subject header.

Let’s scroll down to the publication “School’s Out”.

This screen looks a bit different, right? That’s because a new function of Archive is the ability to loan out books digitally, like a library. These books do not allow copying of their pages, but provide information not available in many resources.

To borrow these books you will need to have an Archive.org account, but the process is relatively simple from there. If the book is available to be borrowed, the button will be blue and your total rented books will be shown. If the book cannot currently be rented, then you can ask to be notified when it becomes available.

Note: Sometimes the check out function will fail or appear to fail due to server errors. Try refreshing the page if you get this error to see if you can access the book, and if not try again or at a later time.

Only one user can check out a book at a time, so be sure when you’re done to check the book back in. You are not mandated to follow the 14 days to return the book, and as soon as the book processes as returned it will be removed from your current holdings and available to other eager readers.

When you enter a book on Archive, it will not carry forward your search results. Make sure to have them on-hand so you can enter them in the search bar located at the top right of the page.

You will find that if you attempt to input “video game” plus “Virtuality” in the search bar you will not get any results. When Archive searches on a per-document basis, it treats lumped search terms as a single phrase that it must find in the document, like “video game Virtuality”. Searching just “video game” or “Virtuality” will get you the results you want.

I hope that this guide has been helpful in learning how to search Archive.org and learn some of its hidden features. Now there are still some limitations to the Internet Archive at the moment, the largest one being that it’s OCR and search capabilities for languages not in Latin text is quite lacking. Do not expect to find a lot of Japanese information for instance without extracting the documents yourself. The inability to customize searches to eliminate some of the erroneous publications is also a hurdle at present, if not a particularly large one.

With the ever-expanding publication-base of the Internet Archive, there will continue to be new information always rolling in. A good way to keep up on some of these new additions is to sort by “Date Archived” to be aware of any larger developments.

While the Internet Archive is a fantastic resource though, it doesn’t quite have everything. In the next post we’ll be talking about the University of Minnesota’s print archive available at the Hathi Trust Digital Library and how it links into the library searcher WorldCat.

All the best!

– Ethan Johnson