Activision was in a precarious place in 1988. Still recovering from the 1983 US console industry crash—and heading right into a new hardware generation—Activision was at risk of going under and in need of a new direction.

One of the people in charge was William Volk, the vice president of technology at Activision from 1988–1994. Volk’s job was to figure out everything related to technology: what platforms they should support, what engines, and where they should be investing their efforts.

Last year, William Volk donated a tape backup of his old work hard drive to the Video Game History Foundation. Now that we’ve recovered the data, we’ve opened the William Volk papers in our digital library, filled with hundreds of documents that offer rare insight into executive-level management from the early history of one of the biggest game companies.

What we found

William Volk kept extensive records of his time at Activision, even on projects he wasn’t directly involved with. In the Volk papers, you can find development timelines, memos and correspondence about new products and hardware, and write-ups about game industry conferences.

Our video goes over a bunch of the materials you can find in this new collection. Here are a few highlights…

Growing, but cautious

One thing we noticed is that while Activision was recovering from their bankruptcy, they were conservative with what games they published and what they were willing to take risks on. William Volk had a document tracking games that were being pitched to Activision, and they seem to have declined almost every single one, including some titles we previously didn’t know had been submitted to Activision.

It comes through in other places too, like the Game Boy port of the game Death Track, developed by Argonaut Software but never actually published. It looks like Activision made the call that they were not comfortable releasing the game unless it had a license attached to it to ensure that it was actually going to sell enough to justify the project. Activision tried seeking out the Mad Max license to put on the game, and when that didn’t come through, it was canceled. Game history researchers already knew that Death Track was canceled close to release, but this sheds new light on why it was canceled.

For another example, consider the game Radical Rex. According to a development timeline in Volk’s papers, the production of Radical Rex hit a snag early on when the Activision sales team raised concerns. The game was originally titled Baby T-Rex, and that may have been the sales team’s issue (how well was a game called Baby T-Rex actually going to sell?). Activision ended up meeting with developer Beam Software to get some reassurances about the game, and then shortly after, they held a focus group and selected a new title. It was a precarious time for Activision, and at this point, they weren’t going with anything that didn’t have strong sales and marketing potential right out of the gate.

New information about unreleased games

Activision had many titles in production in the early 90s, and quite a few of them never came out. From the production schedules and documents that Volk kept on his hard drive, we can learn a lot about what some of these games were and what happened to them.

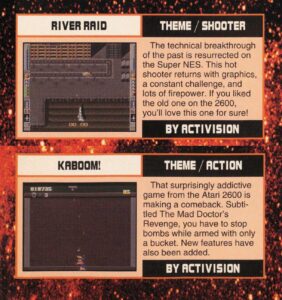

Of greatest interest to our community: Activision had planned to relaunch some of their old Atari franchises with new versions of River Raid, Kaboom, and Pitfall. Although Pitfall: The Mayan Adventure did come out, we never heard much about River Raid: Mission of No Return or Kaboom!: The Mad Doctor’s Revenge, apart from some limited coverage in Electronic Gaming Monthly.

From the Volk papers, we now know that River Raid was being developed by Beam Software, and Kaboom was being made by Sculptured Software, two studios that did a lot of this type of game development outsourcing. Both games were canceled internally in June 1993, just weeks after they were demoed at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show. Seeing how only one magazine even bothered covering both games, we’re guessing the tepid public response at CES played a role in these two titles getting shelved.

There’s also fresh information about the unrealized third game in the Planetfall series, which entered production in 1993. We now know that it was going to use the same engine as Return to Zork, and according to his contract, Planetfall author Steve Meretzky was due to come back as the designer and, basically, their storymaster. It was due out in September 1994 and was originally planned for all major CD-based systems, including—believe it or not—the “Nintendo CD,” making this one of the only games we can actually confirm was being planned for the system.

And a personal favorite: Volk had a design document for something called Dinosaurs, a CD-ROM adventure game starring a talking dinosaur named Struther, which was intended to kickstart a media franchise with spinoff games. This is the first we can tell anyone has heard about this.

And more!

There’s tons more in here that we didn’t catch, especially around details for games that we don’t know as well. Volk was also one of the co-founders of the Lightspan Partnership, a company that produced educational games for the PlayStation, and we haven’t even dug into that part of his papers!

This is our favorite type of collection to add to our digital library. We know that researchers are going to enjoy going through these papers and making connections we’ve never thought of before. This is the sort of material that gets cited in books—and who knows, if this collection excites you, maybe that could be your book!

Recovering the data

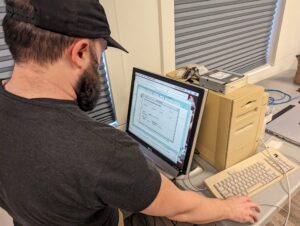

Volk’s hard drive backup was on a Macintosh-formatted data tape. To recover the data, we tapped our friend Keith Kaisershot, who is local to VGHF and had a vintage Mac setup that could read data tapes.

Once we recovered the files, we went through Volk’s drive and removed sensitive, proprietary, or personally identifying information. We always retain the original disk images, but if we’re sharing someone’s documents in our digital library, we want to make sure we’re doing it responsibly. Even if someone’s contact information on a hard drive from 1992 is long out-of-date, we remove that data from publicly accessible copies as a matter of policy.

We identified personally identifiable information using Tessa Walsh’s tool Bulk Reviewer, then redacted them using a custom tool cooked up by Matt, a volunteer on the Video Game History Foundation Discord. In total, we redacted thousands of emails and phone numbers.

While our digital preservation system Preservica does a great job handling common filetypes, like documents and spreadsheets, several of the files in this collection needed extra attention. For example, some of Volk’s earliest documents were created with MacDraw, a vector graphics program that’s been discontinued for decades. In order to make these files viewable, we put together a manual pipeline where we converted MacDraw files to Macintosh PICT files inside a Macintosh emulator, then converted those into rasterized graphics files, and then converted those into text-searchable PDFs.

Once we had all the workflows in place, the process of redacting and processing Volk’s backups took about two months, on-and-off with tandem with other projects.

When you’re working with obsolete hard drives, the most best way to access the files is emulation. Rather than manually migrating thousands of files to new formats, you can set up a virtual machine with the right software to read the data as it was originally saved. However, that’s currently not practical for us to implement in our digital library. With the tools we have, our best option is to migrate some of these unusual file formats so they’re presentable in any form.

The end result is that you can view these documents directly in your web browser, without any other external work needed on your part. And importantly, now we have the tools and experience to do this even more effectively in the future.